PETER AMAN’S BOLD MAYORAL APPEAL TO ATLANTA’S BLACK VOTERS HAS TAKEN ROOT. NOW, IS IT ALSO TAKING OFF?

By Maynard Eaton

Peter Aman, Atlanta’s former Chief Operating Officer, brazenly put the issue of race on front street July 31st when he kicked off his quixotic bid to be elected Atlanta’s next mayor. “Race frames this election,” he opined. The cachet of that compelling comment has righteously resonated with Black voters, and reportedly catapulted his campaign.

Now Aman is convinced that pronouncement and passionate campaign pursuit is paying off as we near election day. He’s come from an improbable nobody to number three in the polls, with a betting chance to win a spot in the anticipated runoff election.

“The reality is we are less than two weeks away and who can win? Who has what I’m characterizing as a combination of quality and striking distance, and that person is Peter,” says Mtamanika Youngblood, a revered Black community activist who is credited with orchestrating the revitalization of Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward and the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic District as the founding executive director of the Historic District Development Corporation [HDDC]. “He tracked me down seeking my opinion about Confederate Avenue and being very clear about the fact that if he lost because he wasn’t the best candidate, that’s okay! If he lost because he wasn’t Black, he would be okay with that but didn’t want to lose because he wasn’t the best candidate. I think it indicates the quality of the man and I don’t make decisions quickly or lightly. It’s taken me all year.”

Youngblood, who is now President and CEO of Sweet Auburn Works, is one of four prominent female leaders who recently publicly endorsed Aman’s mayoral candidacy.

Aman is one of the three white candidates in the field of ten running for the office. He is boldly making a purposeful pitch to Atlanta’s coveted black electorate. If victorious, Aman would be Atlanta’s first white mayor in 43 years. That’s when the late Mayor Maynard Jackson defeated incumbent Sam Massell in 1974.

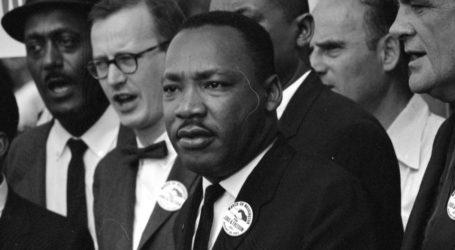

“It matters a lot in terms of honoring and paying homage to the leaders that built Atlanta,” Aman tells this reporter during a NEWSMAKERS Live interview recently about the possibility of becoming Atlanta’s first white mayor since Massell. “One of the things I talk about often is the importance, particularly for me, of recognizing how Atlanta has been built over the last five decades. That’s why our offices are in The Odd Fellows building on Auburn Avenue. The election of Maynard Jackson put in place a new era for Atlanta that we are still reaping the benefits of, and it’s very important to acknowledge that.” He says he will leave it to the voters to speculate how Mayor Jackson would be feeling about his possible election.

Now meet another Jackson, and yet another fervent Aman supporter; an accomplished Southwest Atlanta media and public relations professional with a bona fide Black Atlanta pedigree. She’s Kelley Bass Jackson, the former daughter-in-law of Mayor Maynard Jackson, who lives on Cascade Road in the heart of SW Atlanta just blocks from the homes of former mayors Shirley Franklin and Andrew Young. Jackson has not only enthusiastically endorsed Aman, she also works for him.

Given the City Hall corruption scandal, Jackson argues it’s Aman’s content and character that count—not his color. “It says that this candidate is white as all get out; but he is open-minded, thoughtful, compassionate, empathetic, and smart,” opines the former Deputy Communications Director for former Georgia Attorney General Thurbert Baker. “He can steer us in the right way.”

Jackson has deep-seeded Atlanta roots; her mother was a civil rights activist and her grandfather was one of Atlanta’s most popular restaurant owners. Carmen Alexander Bass, and two other black tennis players integrated the then all-white Bitsy Grant Tennis Center in Buckhead at the behest and coordination of the late Julian Bond back in the late 60’s. For 50 years Jackson’s grandfather, Ernest Alexander, a widely respected businessman, was the legendary owner Alec’s Barbeque on what was then Hunter Street. Now, it is Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

With such rich black family history, Jackson admits her support for Aman’s candidacy puts her in an awkward, if not, tough position.

“Yes, it does,” she says contritely. “Although I remember Sam Massell as mayor, when Maynard was elected the feeling in Atlanta was tantamount to when Obama was elected president. It was glorious. And we’ve enjoyed a tradition of black mayoral leadership ever since. The desire, in the community, to have a black mayor is endemic. However, if a collective desire to have a black mayor existed among the other candidates, they all would not have run against each other. I’m not wed to having a black mayor. I want a great mayor who cares about black people, and serving the least of these.”

The ebullient and politically savvy Jackson, who has also worked as a communications consultant for The Andrew Young Foundation, recently hosted a robust fundraiser for Aman at her home, and he was grilled by her neighbors and friends with some tough questions.

Renita Shelton, who lives nearby, asked Aman, “What issue do you wish the candidates were talking about more during this election?”

“It’s the issue of race,” he replies. “I’m a white guy running for mayor and I’m on track to do very well. That’s a pretty big deal to have a white male mayor in the city of Atlanta for the first time in 50 years. Nobody wants to talk about it.”

“They talk about it, but not out loud,” Jackson chimes in.

“It’s a lens to how everybody looks at me,” Aman adds.

Southwest Atlanta is under siege some homeowners there complain. They lament that gentrification is rampant, but development is virtually non-existent. “There are no construction cranes dotting the skyline south of I-20,” says realtor Rodney Harris. “We’ve been forgotten. I’m afraid we are going to be priced out of Southwest Atlanta within five years. Homes that were valued at $60,000 are now selling for $300 thousand with a little renovation.”

Aman promises his administration will remedy that vexing problem. “I say this all the time, we are forcing out of Atlanta the very people who built it; that’s just what we’re doing,” he says during Jackson’s informal fundraising gathering.

He continues, “If you want single-family houses on a quarter acre lot, you need a zoning code and that’s why we have to talk to each neighborhood to understand what they want. Not everybody gets what they want but the zoning codes make sure you’re getting the right development. Making sure there’s affordable housing is one of my top priorities and what we must do is use every tool in our toolbox. If you think about city government, there are about 15 different tools that you can use for affordable housing. When I say affordable, I mean about $450 a month to $500 a month because that means you can afford it on minimum wage.”

In 1963 Mayor Ivan Allen’s administration erected a wall on Peyton Road separating the black and white communities. It was quickly dubbed “Atlanta’s Berlin Wall” by an angry black community, and the resulting national media attention proved embarrassing to a city conscious of its image regarding race relations.

The realtor Rodney Harris was raised on Peyton Road, and was one of the first to move there after the wall was ruled unconstitutional. Now, he’s strongly considering voting for Aman.

“I’d vote for whoever I think is going to be best for the city period as long as, they have a clear empathy level for what’s going on in the city,” he says. “It’s about what are you doing for the city. I don’t want to hear rhetoric, I want action. I was impressed with what he had to say and his thought pattern because I knew of his experience. I was impressed with what he had to say about transportation, the re-development of the city, and understanding the economic disparities. Also, Aman’s understanding what needs to happen to correct the problems. This is a very pivotal time for Atlanta.”