Outside Influence: A Third Party Timeline

Frustrated by the two-party system? Polling shows you’re not alone, with more Americans than ever supporting the idea of a third party. But the winner of November’s presidential election will be either Biden or Trump, and voters weighing other candidates need to consider if a protest vote to end the duopoly might instead help end our democracy. In the May+June 2024 issue, we examine the past and present of third-party outsiders, and how they could upend this year’s race. You can read all the pieces here.

Even before the last shots of the Revolutionary War were fired, John Adams wrote a friend to warn, “There is nothing I dread so much as a division of the Republic into two great parties.” Alas, political scientists will tell you the winner-takes-all system the founders established virtually ensures consolidation into just two rival blocs. But that hasn’t stopped third-party and independent challengers from repeatedly rising up. They’ve sometimes pointed the way to a new politics, and sometimes scuttled other candidates’ path to power—a role that the 21st century’s razor-thin presidential elections have made all the more nerve-wracking.

William Wirt

Library of Congress

1832: By carrying Vermont, former Attorney General William Wirt, once described as “possibly the most reluctant and most unwilling presidential candidate ever,” is the first minor-party contender to win electoral votes. Despite having been a Freemason, he ran with the Anti-Masonic Party, an upswelling of Protestant voters suspicious of a secret society of elites.

Andrew Jackson

Library of Congress

1834: Andrew Jackson’s populist presidency undercuts the Anti-Masons appeal, and his opponents organize as the Whigs, borrowing the name from English anti-monarchists. Over the next two decades, the Whigs elect two presidents—both of whom die in office.

Joseph Smith

Library of Congress

1844: In part to call attention to anti-Mormon oppression, church founder Joseph Smith launches a White House campaign. After opponents allege he practices polygamy, he becomes the first presidential candidate to be assassinated, killed by gunfire in a mob attack.

Free Soiler broadsheet.

Library of Congress

1848: The Free Soil Party forms to oppose the westward expansion of slavery. Despite having spent most of his career insisting the federal government had no power to end slavery, former President Martin Van Buren, whose son was a major Free Soiler, runs and wins 10 percent. Two party members are elected to the US Senate, one of whom is nearly beaten to death in the Capitol by a slaveholding representative.

Poster for the Know Nothings; Millard Fillmore.

Library of Congress (2)

1854: An influx of Irish Catholic immigrants spurs Protestants to form the so-called Know Nothing Party, whose platform promises to strip newcomers’ voting rights and insists “Americans Should Rule America.” They eventually win five governorships and nearly every seat in the Massachusetts Statehouse, with their 1856 presidential candidate, former Whig President Millard Fillmore, earning 22 percent.

Abraham Lincoln flyer.

Library of Congress

1860: In a four-way race, former one-term Whig congressman Abraham Lincoln is elected president as a Republican after divisions over slavery effectively destroyed the Know Nothing and Whig parties, making the GOP the only minor party to become a major party in US history. (Fun fact: Lincoln seeks reelection on a newly created National Union Party line, selecting a Democratic running mate who supported the Civil War.)

James B. Weaver.

Library of Congress

1873: A financial panic spurs farmers and laborers to create the Greenback Party, which popularizes the idea of introducing paper money to ease mass debt. Fourteen members get elected to Congress, but, as economic conditions improve, their 1880 presidential candidate, former General and Rep. James B. Weaver, nets just 3 percent.

1892: Former Greenbacks organize into the more radical Populist Party. Weaver takes up their mantle and wins five states on his way to 9 percent of the vote. His candidacy attracts progressive Republicans, which may have eased Democrat Grover Cleveland’s path to the presidency. Many Populist proposals—like direct election of senators, a graduated income tax, and the eight-hour workday—are enacted by Congress.

Teddy Roosevelt.

Library of Congress

1912: Feeling disrespected by his anointed successor William Taft, ex–Republican President Theodore Roosevelt runs against him on the Progressive, or Bull Moose, party ticket. He finishes second despite being shot while stumping in Milwaukee, dividing his old party’s voters and helping Democrat Woodrow Wilson win.

Eugene Debs

Library of Congress

Meanwhile, Eugene Debs earns 6 percent—the most ever for a socialist party.

Robert M. La Follette.

Library of Congress

1924: As conservatives consolidate their hold on the GOP, Robert “Fighting Bob” La Follette quits to start his own Progressive Party, winning 16.6 percent of the national vote and carrying his home state of Wisconsin. Under the guidance of his sons, the left-of-center party remains a major player there until 1946.

1930: In Minnesota, the Farmer-Labor Party, also formed by breakaway liberal Republicans, elects a governor. After Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal realignment permanently undercuts the appeal of left-leaning third parties, it merges with the Democrats to form the DFL, as Minnesota’s Democratic party remains known today.

Henry A. Wallace.

NY Daily News Archive/Getty

1948: Henry A. Wallace, once FDR’s vice president, reanimates the Progressive label and mounts an anti–Cold War protest campaign. When Gallup asks voters if his “third party is run by Communists,” 51 percent agree. Meanwhile, after Hubert Humphrey, Minneapolis’ DFL mayor, leads Democrats in adopting a pro–civil rights platform, Gov. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina bolts and runs for president as the States Rights Democratic Party’s candidate, hoping to block Harry S. Truman’s return to the White House. He fails, but wins four Southern states.

A pin supporting George Wallace.

MPI/Getty

1968: Democrats’ continued embrace of civil rights prompts George Wallace, Alabama’s segregationist governor, to launch the American Independent Party. He’s forced to run on six different party lines, but still manages to win five Southern states and 46 electoral votes in a counterculture-attacking campaign that attracts many Democrats as Humphrey, the party’s nominee, goes down to Richard Nixon. Four years later, most of Wallace’s ’68 voters support Nixon’s reelection, ushering in the GOP’s Southern dominance.

George Wallace campaigning in 1968.

AP

James Buckley.

Bettmann Archive/Getty

1970: James L. Buckley, the brother of National Review founder William, wins a Senate seat as a candidate of New York’s Conservative Party, which owes its existence to the state’s “fusion voting” system allowing politicians to appear on multiple parties’ ballot lines.

1974: Post-Watergate reforms to the Federal Election Campaign Act, described as a “major party protection act” by political scientists, will dole out hundreds of millions of tax dollars to Democrats and Republicans. Minor parties can qualify for smaller subsidies if their presidential candidate gets more than 5 percent of the vote.

John Anderson.

David Hume Kennerly/Getty

1980: John Anderson, a longtime Republican member of Congress whose liberal drift alienated him from the party, mounts an independent bid after losing the GOP presidential primary to Ronald Reagan. Incumbent Jimmy Carter refused to face him in a three-way debate, worried doing so would eat into his own support, but the president performs so poorly that the 7 percent Anderson earned isn’t a factor in Reagan’s win.

Bernie Sanders.

Laura Patterson/CQ Roll Call/Getty

1981: Bernie Sanders, who already had been affiliated with two minor left-wing parties, narrowly becomes mayor of Burlington. Though he wins the race as an independent and will remain one for the rest of his career, his supporters eventually organize into the Vermont Progressive Party, often described as one of the most successful local parties in modern US history.

Campaign buttons from 1988 and 1992.

Fotosearch/Getty

1992: Spring polling shows independent Ross Perot, whose “clean out the barn” candidacy centers anxieties around federal debt and foreign trade, in the lead for the presidency, forcing the Commission on Presidential Debates, a nonprofit organization controlled by former Democratic and Republican officials, to allow him to participate. Perot earns 19 percent, finishing second in Maine and Utah. He then finances the launch of the Reform Party.

Ross Perot.

Peter Muhly/AFP/Getty

1996: Perot’s follow-up campaign nets only 8 percent—still enough to bring the next Reform Party nominee $12.6 million under FECA.

Jesse Ventura

Craig Lassig/Getty

Two years later, former WWF star Jesse “The Body” Ventura wins Minnesota’s governorship for the party after appearing nearly nude in a campaign ad.

1997: The left-leaning New Party loses a Supreme Court case to spread fusion voting nationwide. Members regroup to form the union-backed Working Families Party in New York state. Today, it usually bestows ballot lines to left-leaning Democrats, including Democratic Socialists of America members. In Hartford and Philadelphia, WFP politicians have been elected under rules limiting one-party control of city councils.

Donald Trump greets Jesse Ventura.

Richard Drew/AP

2000: The Reform Party’s assets lure a diverse crop of opportunists, including Donald Trump, who wins its California primary before withdrawing. While the formal nod goes to former Reagan adviser Pat Buchanan, supporters of John Hagelin (who is also the candidate of the transcendental-meditation-affiliated Natural Law Party) stage a rival convention. As states debate the true winner, some resort to drawing names from a hat. Ventura quits, blasting his onetime allies as “hopelessly dysfunctional.”

Ralph Nader on the floor of the 2000 Republican National Convention.

Chris Hondros/Newsmakers/Getty

In the final days of the election, Democratic VP nominee Sen. Joe Lieberman targets consumer advocate Ralph Nader’s left-leaning Green Party campaign, warning potential Al Gore voters that supporting Nader could “help elect somebody that is diametrically opposed.”

Joe Lieberman.

Bob Child/AP

2006: After losing a Democratic Senate primary, Lieberman wins reelection as the candidate of the “Connecticut for Lieberman Party.” About a year later, he endorses John McCain’s GOP presidential campaign.

2010: The Supreme Court’s January Citizens United decision allows nonprofits to collect big money, boost candidates, and shape politics with little transparency. Later in the year, Lieberman helps launch No Labels, one such centrist group, which refuses to disclose its major financial backers. In 2023, as the organization prepares to support an independent ticket to challenge Joe Biden that never materializes, two past donors step out of the shadows to file a lawsuit alleging breach of contract, saying they “never” would have supported “such a gambit.”

Buttons backing Jill Stein.

Helen H. Richardson/Denver Post/Getty

2016: Green Party candidate Jill Stein, who announced her exploratory committee on a Kremlin-propaganda channel and infamously sat with Vladimir Putin and Mike Flynn at a Moscow banquet, receives more votes than Hillary Clinton’s margin of defeat in three Rust Belt states with the support of Russian social media trolls.

Jill Stein in 2016.

Christopher Evans/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald/Getty

While Clinton supporters blast Stein as a spoiler and stooge, they also help her raise $7 million to pursue recounts. Critics later question where the money went.

Cornel West campaigning in 2023.

Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times/Getty

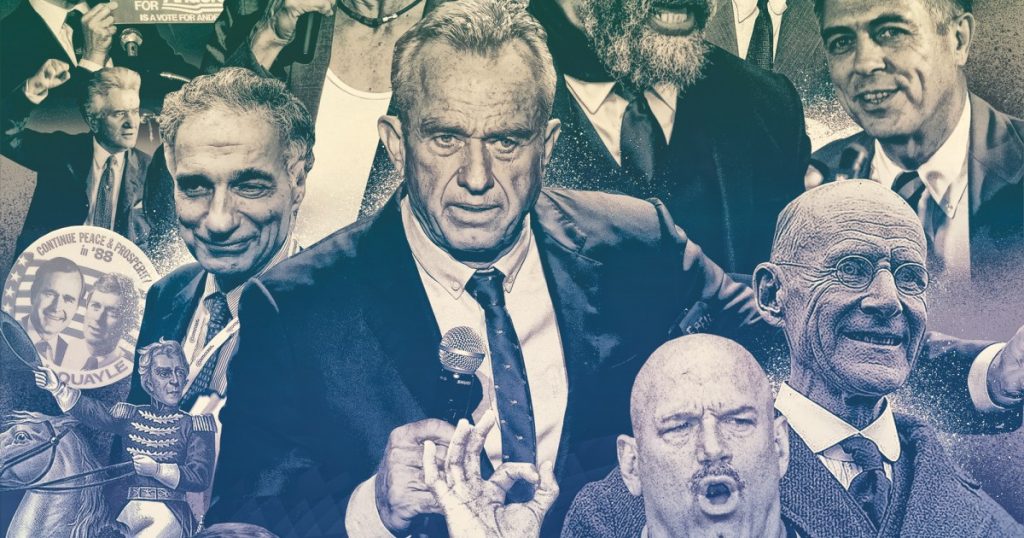

2024: Republicans plan efforts to aid third-party and independent candidates, as Democratic strategists warn they could derail Biden’s reelection. Early polling shows another Stein bid Cornel West, and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. drawing support from almost one in five voters.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announces his independent bid.

Jessica Kourkounis/Getty

Top image credits: Campell: Library of Congress; Webster: Library of Congress; Debs: Library of Congress; Nader: Chris Hondros/Getty; Wallace Button: MPI/Getty; Buchanan: Diana Walker/Getty; Ventura: Craid Lassig/AFP/Getty; FL Vote: Bruce Weaver/AFP/Getty; Anderson Button: Hulton Archives/Getty; Stein button Cluster: Fotosearch/Getty; H. Wallace: NY Daily News/Getty; Buckley: Bettmann/Getty; George Wallace: Getty; Roosevelt: Bettmann/Getty; 1988-1992 button collection: Helen H. Richardson/Denver Post/Getty; Sanders: Laura Patterson/CQ Roll Call/Getty; Anderson: David Hume Kennerly/Getty; Stein sign: Erik McGregor/Lightrocket/Getty; Stein: Christopher Evans/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald/Getty; West: Francine Orr/LA Times/Getty; Kennedy: Mario Tama/Getty; Kennedy: Jessica Kourkounis/Getty; Perot: Peter Muhly/AFP/Getty; LaFollette: Library of Congress; Know Nothings: Library of Congress; Jackson: Library of Congress; Free Soil: Library of Congress; Wirt: Library of Congress