Florida Gave Former Felons the Right to Vote. Legislators Want Them to Pay First.

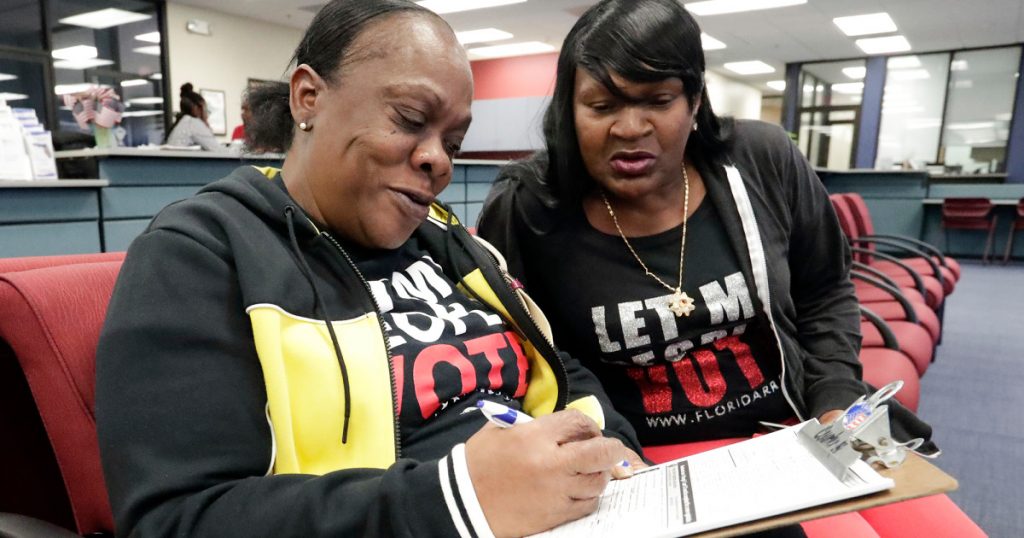

Thanks to Amendment 4, Yolanda Wilcox, left, fills out a voter registration form as her friend looks on at the Supervisor of Elections office on January 8 in Orlando John Raoux/AP

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

Last November, Florida passed a ballot measure to reenfranchise as many as 1.4 million people with felony records, the largest expansion of voting rights in decades. But less than six months after the historic move, state lawmakers are considering legislation that would make it harder for some of them to vote by requiring them to first finish paying all court fines and fees.

Before the ballot measure went into effect in January, Florida was one of only four states that permanently blocked former felons from participating in elections, a policy that traced back to the Jim Crow era and kept 10 percent of Floridians—and 1 in 5 African Americans in the state—off the rolls. Amendment 4 restored voting rights to Florida citizens with felony records who had completed their sentences (except for those who were convicted of murder or sex crimes).

State lawmakers now argue that aspects of Amendment 4 are confusing and require clarification. On Tuesday, a House subcommittee approved a bill that would prevent people with felony records from voting until they finish paying all court fines and fees, including “any cost of supervision” like parole, even if those fines and fees were not spelled out by a judge as part of the person’s original sentence. Previously, people with felony records only had to pay back restitution to a victim to get their rights restored, according to the Tampa Bay Times.

“It’s blatantly unconstitutional as a poll tax,” Rep. Adam Hattersley said.The bill was introduced last Friday and passed out of committee along party lines, with Republicans in favor. The Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, a group that pushed for Amendment 4, slammed it as an “unconstitutional overreach” that “would restrict the number of people who would otherwise be eligible to vote.” Others argue the bill would unfairly burden low-income people who can’t afford to repay all their fines. “This will inevitably prevent individuals from voting based on the size of one’s bank account,” Kirk Baily, a political director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida, said in a statement. “It’s blatantly unconstitutional as a poll tax,” Rep. Adam Hattersley (D-Riverview) told the Tampa Bay Times.

Republicans dismissed that characterization. “To suggest that this is a poll tax inherently diminishes the atrocity of what a poll tax actually was,” state Rep. James Grant, chairman of Florida’s House criminal justice subcommittee, told the newspaper. Grant argued the bill was also needed to clarify other “super-ambiguous” aspects of Amendment 4, including which offenses qualify as sex crimes.

Florida’s felon disenfranchisement policies have racist roots that began after the Civil War, as Mother Jones‘ Ari Berman explained in a deep dive about Amendment 4 before it passed in November:

After the Civil War, the white Confederates who still controlled Florida had a problem: The state had been forced to accept the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, which guaranteed equal rights for newly freed slaves, in order to rejoin the Union, and now black registered voters outnumbered white ones. White Floridians responded by adopting a constitution in 1868 that disenfranchised anyone with a felony conviction and added to the felony roster a variety of crimes they believed African Americans were likelier to be convicted of. One Republican leader said the law would keep the state from becoming “niggerized.” A decade later, more than 95 percent of people in Florida’s convict camps were African Americans.

Today, Florida is one of the country’s most important swing states—lending extra weight to the issue of who gets to vote, especially for Republicans. According to an academic study of the 2000 presidential election, Al Gore would have defeated George W. Bush by as many as 60,000 votes in Florida if it weren’t for felony disenfranchisement policies. In 2007, when then-Gov. Charlie Crist, a moderate Republican who later became a Democrat, decided to restore voting rights to 40,000 people with felony records, about 60 percent of them registered as Democrats.

As the bill moves out of committee for broader consideration, advocates of Amendment 4 are urging state lawmakers to amend it and remove financial barriers to voting. “For the millions of us who are impacted by Amendment 4, we will fight any measure that denies people their constitutional rights,” Desmond Meade and Neil Volz, advocates with the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition who both registered to vote because of the ballot measure, wrote in an op-ed. “We will do that now, we will do that in 2020, and we will do that beyond.