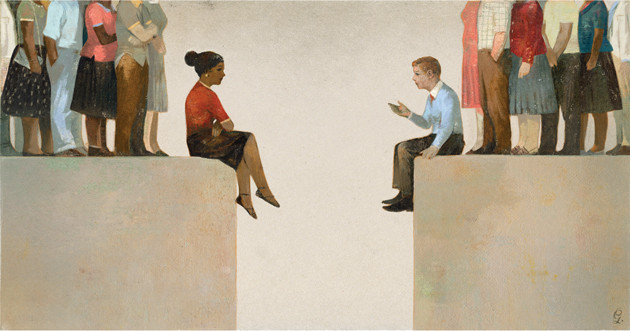

You Won’t Change Your Cranky Conservative Uncle in One Dinner Conversation

Gérard DuBoisLast October, shortly before the election, I came across a startling photo from Oakland, California, circa 1969. Two men stood side by side: a black guy in a beret and leather jacket and a white guy in a denim vest emblazoned with the Confederate flag. The white guy was part of the Young Patriots, a group made up of poor white Southerners. The black guy was a Black Panther.

The two organizations, along with a Puerto Rican group called the Young Lords, had formed what they called the Rainbow Coalition—a name Jesse Jackson would revive and popularize 15 years later. They had teamed up to fight for low-income issues like fair wages and access to health care even though, when the Panthers first approached them, some of the Young Patriots were enamored with racist ideas and symbols. “It wasn’t easy to build an alliance,” former Black Panther Bobby Lee once recalled. “I had to run with those cats, break bread with them, hang out at the pool hall. I had to lay down on their couch, in their neighborhood. Then I had to invite them into mine.”

“The powers that be have manipulated us into feeling like we are far more divided than we are.”After Donald Trump was elected, that photo kept returning to my mind. Amid all the banter about how to reach white working-class voters who defected to Trump—or, conversely, about why progressives should leave those “deplorables” behind and focus on voters of color—I’ve found myself vacillating between these two points of view. I don’t believe in writing people off, and like many journalists I actually enjoy engaging with belief systems different from my own. But engagement only works when people can share a set of facts, or at least agree that facts exist. As we withdraw further into our political, geographical, and informational silos, any quest for common ground feels futile. So why even make the effort?

And yet. Something about that conclusion bothered me, so I asked Joan Blades, the co-founder of MoveOn.org, to lunch. In 2010, Blades teamed up with former Republican operative Amanda Kathryn Roman to form Living Room Conversations, an organization that fosters “transpartisan” connection through intimate in-person discussions. Anyone can download their materials for free. In short, two co-hosts with differing political views each invite two friends to join them in a structured chat about a topic such as immigration or “fake news.” (A sister project, Mismatch, pairs students at geographically and socioeconomically disparate schools for LRC-style video conferences.)

Blades got to know right-wingers such as Tea Party Patriots co-founder Mark Meckler, whom she now calls a friend. “I’m deeply concerned that as we live in increasingly separate narratives, our capacity to have a democracy is diminished,” she told me. “The powers that be have manipulated us into feeling like we are far more divided than we are.”

She’s not the only one trying to fix this. A slew of related initiatives have sprung up—particularly since the election. Some, such as AllSides, CivilPolitics.org, Hi From the Other Side, Mismatch, Unbubble, and the Village Square, have a nonpartisan mission: encouraging politically dissimilar Americans to interact respectfully. Others, like Knock Every Door, support progressive candidates by bringing in volunteers to pursue open-ended talks with nonvoters and Obama voters who flipped to Trump.

In a Pew Research Center poll, 55 percent of Democrats and 49 percent of Republicans said the other party made them feel “afraid.”They have their work cut out for them. In a recent study, researchers at the University of Colorado-Boulder found that subjects who engage in group conversations with politically like-minded people tend to emerge with a more extreme attitude. What’s more, many participants were oblivious to this effect, misremembering how they’d felt about an issue before entering the echo chamber. Last year, for the first time since it started asking back in 1992, the Pew Research Center found that majorities from both parties held highly unfavorable views of their counterparts—55 percent of Democrats and 49 percent of Republicans said the other party made them feel “afraid.”

To assuage these fears, Living Room Conversations asks its participants to follow ground rules about respect and listening. Only after talking about their values and hopes for the country do they delve into thornier issues such as race or homelessness, using a few guiding questions. Afterward, people are invited to reflect on their experiences. Nearly all the participants who submitted feedback forms over the past three years said they had left the conversations feeling closer to those on the other side, learned something new or valuable, and found some common ground. “My first Living Room Conversation, half the table cried,” says Megan Range, a right-of-center Bay Area resident who has since participated twice more.

Because participants don’t register with the website, Blades can’t offer hard numbers, but she figures the hundreds of feedback forms she’s received represent a fraction of the total. One Texas Episcopal church holds conversations monthly, as does the city of Saratoga, California. And there’s been a surge of interest from community leaders and funders since the November 2016 election, resulting in partnerships with at least a dozen like-minded groups. “The practice is proven and the time is right,” Blades says. It’s not a quick fix, though. “People are almost never transformed in a single conversation,” she cautions, “but their feelings about each other are. And that’s the opening for all sorts of deep transformation.”

“Whatever empathy and curiosity progressives have felt toward conservatives, I worry that Trump has vaporized it.”Transformation might mean coalition-building—as liberals and conservatives have done on criminal justice reform—or simply toning down the most hurtful rhetoric. Blades cites her relationship with LRC team member Jacob Z. Hess, a Mormon conservative living in rural Utah. Hess, who has a Ph.D. in psychology and has co-authored a book on right-left conversations, says talking to Blades has moderated his views. “I have more uncertainty and curiosity,” he says. “I care about climate change because Joan does—because I care about Joan.” But Hess, who was never a Trump supporter, also worries that talking has gotten harder since the election. “Whatever empathy and curiosity progressives have felt toward conservatives, I worry that Trump has vaporized it,” he told me.

One obstacle, according to AllSides founder John Gable, a former Netscape product manager who in earlier days worked for politicians such as Mitch McConnell and George H.W. Bush, is that when one side says “dialogue,” the other side hears “lecture.” “People on the right are scared to have these conversations,” Gable says, “because if you support immigration but you want some limits, people are going to call you a racist.”

That’s precisely why the left needs to keep reaching out, says Kalia Lydgate, the national coordinator for Van Jones’ #LoveArmy, which promotes activism through teach-ins and revival-style events. Some Trump supporters are clearly unapologetic white supremacists, but if you assume they all are, she says, you end up “pushing those people toward the very dangerous subset of people who voted for Trump.”

With that in mind, I attended a presentation called “Reaching Out to Trump Voters,” sponsored by the Berkeley, California, chapter of Indivisible. The speakers, cognitive linguist George Lakoff and sociologist Arlie Hochschild (who has written about Trump supporters for Mother Jones), had essentially the same advice: Don’t argue policy. Political thought springs from moral constructs embedded deep in our neural circuitry, and from governing metaphors—what Hochschild calls “the deep story”—that explain how the world feels. “Telling people the facts over and over and over, that’s not going to do anything,” Lakoff said. “What will work is talking at the level of the heart.”

Trying to persuade a political foe using your own moral framework is a losing game. “You have to empathize with them.”The heart. It’s the corniest, flimsiest-sounding thing in the world, and it seems ill-suited to our current culture. Yet research affirms that homespun qualities like compassion, openness, and humility are key to breaking political logjams. “People think emotionally,” says Peter H. Ditto, a psychology professor at the University of California-Irvine who has found that liberals and conservatives are equally quick to dismiss facts that clash with their worldview. And potent counterarguments, studies show, can actually harden people’s beliefs.

It’s also key to know your rival’s language—liberals tend to frame arguments in terms of kindness and equality, while conservatives favor loyalty, purity, and authority. Trying to persuade a political foe using your own moral framework is a losing game. “You have to empathize with them,” says Matthew Feinberg, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at the University of Toronto.

That takes patience. Joy Peskin, who edits some of my children’s books, told me about an email correspondence she struck up with Rick Perry, a St. Louis Trump delegate she met on a Washington, DC, Metro platform while protesting the inauguration he’d come to celebrate. Perry was put off by the anti-Trump rhetoric on Peskin’s Facebook page and by her barrage of questions—every message felt like a homework assignment. Peskin, in turn, was appalled by links Perry sent her, such as an anti-Black Lives Matter video that showed young black men looting and beating people.

“Once I saw that my misbehavior caused her pain, I was sorry.”She threatened to cut him off but agreed to keep talking as long as they avoided politics. Thus they got to know each other better, and so when they had another big spat—over the Paris climate accord—they were able to work it out. “I was showing her a little lack of respect,” Perry told me. “Once I saw that my misbehavior caused her pain, I was sorry.”

The benefits of conversing with your political opposites may well be intangible. The point, Lydgate says, is not so much about what we want from our foes as what we want from ourselves. “When we think what it would mean to win, it’s that everybody has a place of dignity in our country,” she told me. “Operating out of love is a form of resistance. We don’t want to turn into what we’re fighting.”