What the January 6 Subpoenas Say About Kevin McCarthy

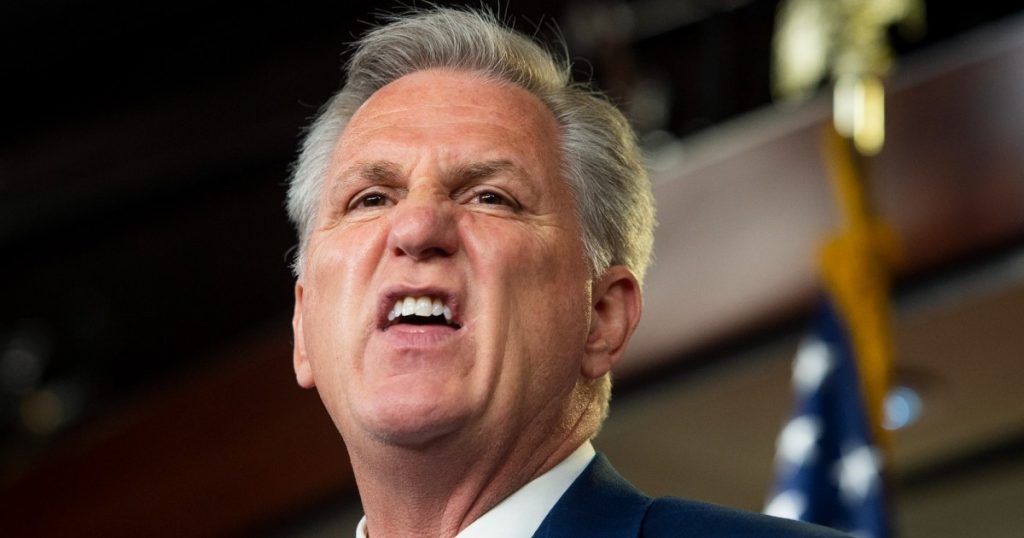

Kevin McCarthy addressing reporters on May 11. Rod Lamkey/CNP via Zuma

Facts matter: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter. Support our nonprofit reporting. Subscribe to our print magazine.Consider Kevin McCarthy. The California Republican on Thursday received a subpoena—along with four of his GOP colleagues—from the committee investigating the January 6 insurrection on Congress, because he has refused to voluntarily provide any information about Donald Trump’s response to the attack. These subpoenas by a congressional committee to compel testimony from members of Congress were accurately described by various publications as unprecedented. But a sitting president refusing to accept defeat and inciting a violent attack on Congress was also unprecedented. These are unusual times, we know. The process—spoiler: the Republicans probably aren’t going to comply—is a bit beside the point.

What is perhaps most relevant here is the world historic cravenness of McCarthy, the House Minority Leader, who—perhaps because of that quality—is likely to become the Speaker of the House next year. The subpoenas highlight the decision by Republican leaders to stonewall and undermine a bipartisan committee of their peers that is looking into an attack on them.

This was not inevitable. McCarthy and Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell both let it be known after January 6 that they’d had it with Trump. “The president bears responsibility for Wednesday’s attack on Congress by mob rioters,” McCarthy said on January 13, 2021. “He should have immediately denounced the mob when he saw what was unfolding.” McConnell even considered voting to convict Trump following his impeachment by the House. If the Kentucky Republican had decided to do so, there was a chance enough Republicans would have joined Democrats to bar Trump from running again.

Once it became clear that Trump had not lost the GOP base through the failed coup attempt, however, McCarthy lurched back into submission. He refused to support a bipartisan commission to investigate the insurrection, and then he attacked the panel created by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi as partisan. After Republican Rep. Liz Cheney (Wyo.) agreed to serve on the committee, McCarthy backed her ouster as GOP caucus chair. Rep. Adam Kinzinger (Ill.), another Republican who joined the panel, is not seeking reelection.

The cynicism of McCarthy’s actions was highlighted last month, when New York Times reporters Alexander Burns and Jonathan Martin revealed he had privately condemned Trump even more forcefully than he did in public after January 6, and had told colleagues that he would call on Trump to resign. McCarthy, of course, denied that report, leading Burns and Martin to release an audio tape confirming their its accuracy and showing McCarthy to be a liar, a revelation he shrugged off.

Unlike McCarthy, the other Republicans the committee subpoenaed Thursday—Jim Jordan of Ohio, Mo Brooks of Alabama, Andy Biggs of Arizona, and Scott Perry of Pennsylvania—have consistently been ardent Trump backers. All four consulted with the president after his defeat on how to use bogus election fraud claims to contest the result. Jordan, who was in touch with Trump on January 6, was among lawmakers who asserted Vice President Mike Pence could use his ceremonial role in certifying election results to block Joe Biden from taking office. Perry advocated for states to send alternative slates of electors who would vote to keep Trump in power. Biggs and Brooks were among lawmakers who Stop the Steal organizer Ali Alexander said “schemed up” with him a plan to “put maximum pressure on Congress” on January 6.

These lawmakers have defended their actions as legitimate attempts to look into voter fraud allegations and spoken publicly about some of their communications with Trump. After Trump revoked an endorsement of his Senate bid, Brooks, for instance, revealed that Trump had pressured him to “rescind the election of 2020.” But they have refused to agree to questioning by the committee.

It is possible to imagine a scenario in which these Republican lawmakers, while critical of the January 6 committee, might have provided its members with information anyway. In January 2021, according to Rep. Jamie Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.), McCarthy promoted the notion that he had confronted Trump during the attack, telling colleagues he had told Trump to “call off the riot”—to which Trump supposedly responded: “Well, Kevin, I guess these people are more upset about the election than you are.” Back then, it might have seemed likely he’d voluntarily agree to share the details of that call with fellow lawmakers. But McCarthy has gambled that attacking the panel is the best way for him to become speaker, at which point he is widely expected to kill the committee. Politically, he might be right. But his character, in these days, is revealed.