What happens next in the impeachment of Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas?

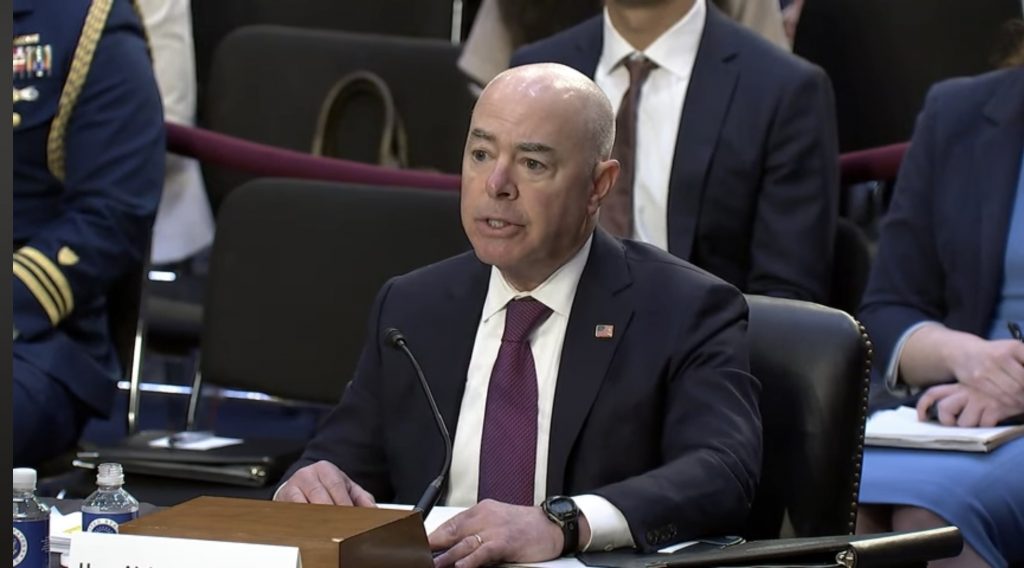

Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas testifies before the Senate Judiciary Committee about the fentanyl crisis on March 28, 2023. (Screenshot from Senate webcast)

WASHINGTON — The U.S. Senate is expected to head to trial later this month after House Republicans impeached Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas Tuesday in a historic move against a sitting Cabinet member.

A special core set of impeachment rules that were last revised in the 1980s requires the body to consider resolutions containing impeachment articles that arrive from the House. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s office said Tuesday night the Democratic-controlled chamber will take action when it returns from recess on Feb. 26.

Senators will be sworn in as jurors the day after House impeachment managers deliver the articles of impeachment, Schumer’s office said, and Senate President Pro Tempore Patty Murray, a Washington state Democrat, will preside.

The House voted 214-213 to impeach Mayorkas on two articles of impeachment, on a second try after an earlier vote on Feb. 6 failed 214-216.

What does the Senate do first?

According to the rules currently on the books, the Senate must act in some way when the articles of impeachment are presented.

For example, senators can follow the already established rules, vote to make new rules or even take a procedural step to dispose of the impeachment resolution.

But just like the Senate’s regular standing rules, the body’s impeachment trial rules are not “self-enforcing.”

“That means that if the Senate doesn’t move to consider the impeachment resolution and have a trial, if they just ignore it, a senator could raise a point of order to enforce them and then the Senate would have a vote on that point of order to decide whether or not they were going to honor their rules,” said James Wallner, senior fellow at the R Street Institute and and political science lecturer at Clemson University in South Carolina.

“But if a senator didn’t raise a point of order, and they all just ignored it, then the Senate could just ignore the rules. Of course, in a situation like this, that’s unlikely to happen,” said Wallner, who writes a helpful blog on what happens inside the halls of Congress.

Wallner was the executive director of the Senate Steering Committee during the chairmanships of GOP Sens. Mike Lee of Utah and the now retired Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania.

“The takeaway is … they have to act in some way,” Wallner said.

The House lawmakers appointed by Republicans as their impeachment managers for the Mayorkas trial include GOP Reps. Mark Green of Tennessee, Michael McCaul of Texas, Andy Biggs of Arizona, Clay Higgins of Louisiana, Ben Cline of Virginia, Michael Guest of Mississippi, Andrew Garbarino of New York, Marjorie Taylor Greene of Rome, Georgia, August Pfluger of Texas, Harriet Hageman of Wyoming and Laurel Lee of Florida.

What will the trial look like?

Schumer has already put to rest the question of the Senate’s initial steps on the articles of impeachment against Mayorkas.

However, because the core set of Senate impeachment rules leave a lot of unanswered questions, senators can chart their own course on the once rare but now more common impeachment trials — for example, how witnesses will be called, when motions are due, and so forth.

The body came up with specific supplementary rules for how to govern the 1999 impeachment trial of former President Bill Clinton, and for the two impeachment trials of former President Donald Trump, in 2019 and 2021, Wallner said.

As long as the Senate waits until the trial is formally underway, any supplementary rules can be adopted by a simple majority.

That will be key for the Democrats who only hold the majority by a slim margin in the upper chamber.

During the first Trump impeachment in 2019, Republicans in the Senate crafted “extremely detailed” rules for the trial, said Matt Glassman, a senior fellow at the Government Affairs Institute, a Georgetown University-run program that offers courses about congressional proceedings to executive branch personnel and others.

The Republican majority decided “when the House would file their motions, when Trump’s team would respond to them, what dates this would happen, what times would this happen, when arguments would happen for these things, and then how much time would there be for questions, how much time was presentations by the House managers and by Trump’s team,” he said.

“And so it very tightly structured the trial, right. And it did not actually leave a lot of room for senators to sort of freelance and make motions,” Glassman said.

“The Democrats tried to amend this, to allow fresh witnesses to be brought in to be deposed or questioned, right, because they wanted additional evidence brought to bear, and the Republicans blocked those amendments,” Glassman said.

The option for a motion to dismiss can be included in the supplementary rules as a way to “short circuit” the trial, Glassman said.

What are Senate Democrats saying?

While Senate Democrats have not yet decided on their supplementary trial rules, Schumer’s office released a statement Tuesday night calling the impeachment vote a “sham” and a “new low for House Republicans.”

“This sham impeachment effort is another embarrassment for House Republicans. The one and only reason for this impeachment is for Speaker Johnson to further appease Donald Trump,” Schumer said, referring to Speaker Mike Johnson of Louisiana.

As for a timeline, once the trial is underway the Senate’s core impeachment rules state that the chamber remains in session “from day to day … after the trial shall commence (unless otherwise ordered by the Senate) until final judgment shall be rendered.”

Glassman points out that the Senate “has routinely used unanimous consent to conduct all sorts of other business during impeachment trials.” The Senate can also structure its rules to make time for other legislative business, as needed, he adds.

A conviction in a Senate impeachment trial requires a two-thirds vote.

How rare is this?

The last Cabinet secretary to be impeached was Secretary of War William Belknap in 1876. The secretary, a former Iowa state legislator, was known for throwing lavish parties on a meager government salary and was eventually found out for his corrupt behavior, which involved taking kickbacks.

According to Senate records, Belknap relinquished his post just before the House voted to impeach him, which technically makes Mayorkas the first sitting Cabinet member to be impeached.

Despite Belknap’s exit, the Senate proceeded with a trial.

Belknap’s unique situation of no longer serving in government but being on trial in the Senate anyhow was a topic of discussion as the Senate in 2021 conducted its impeachment trial of Trump after he left office.

Circumstances aside, impeachment and Senate trials are overall rare, Wallner said.

“They’ve only impeached a handful of people in the House. They’ve only had trials for a handful of people in the Senate. It’s just this is a rare power to begin with,” Wallner said.

“… And I mean, I think to the extent that it is becoming more common today, I think that’s the more interesting story, not so much (that it’s happening) to a Cabinet official, but more to how we conduct our politics.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

The post What happens next in the impeachment of Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas? appeared first on Georgia Recorder.