Trump Explodes at Judge in New York Fraud Trial

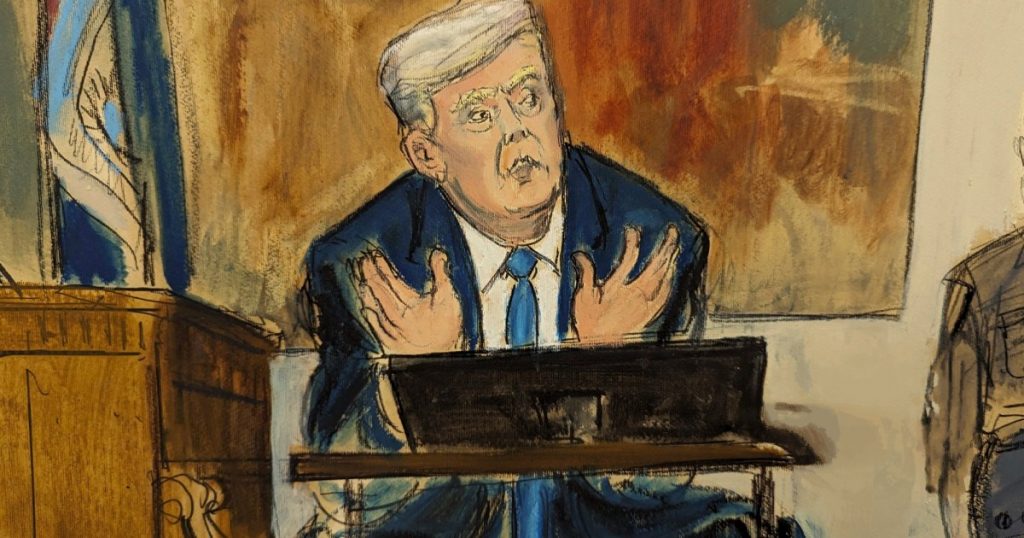

In this courtroom sketch, Donald Trump testifies in New York Supreme Court, Monday, Nov. 6, 2023.Elizabeth Williams/via AP

Fight disinformation: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter and follow the news that matters.When Donald Trump took the witness stand Monday as the defendant in a $250 million civil fraud case, he found himself on a public stage he had no control over—and he hated it. Facing direct questions from New York prosecutors about what role he played in fraudulently inflating his net worth, Trump struggled, and often failed, to maintain his cool. Trump seemed to have come to court prepared to fight with the lawyers from the state attorney general’s office, but judge Arthur Engoron didn’t hesitate to check his efforts to derail the proceedings.

At one point, with Trump blustering about what he believed the banks he did business with were interested in—which was not the question posed to him by Kevin Wallace, the state’s attorney—Engoron turned to Trump lawyer Chris Kise and, with his normally amicable face darkly furrowed, scolded the former president’s team.

“Mr. Kise, can you control your client? This is not a political rally, this is a courtroom,” Engoron barked. “I don’t want him editorializing, or we’ll be here forever, and we’ll accomplish nothing.”

A few minutes later, when Trump again wandered away from the question he’d been asked, Engoron went at Kise again.

“We got another speech,” he groused. “I beseech you to control him—if you can. If you can’t, I will. I will excuse him and draw every negative inference that I can.”

A “negative inference,” in legal parlance, is a conclusion by a court that a defendant who fails to follow the rules must be hiding something negative. In a criminal case, defendants have a constitutional right not to testify; if they choose not to take the stand, that decision can’t be used against them. But in civil court, where this particular Trump’s trial is taking place, defendants have no such right. When Kise protested that Trump—as a central figure to the case—should be allowed to answers as broadly as he wanted, Engoron made it clear he was done giving Trump the benefit of the doubt.

“No, I do not want to hear everything this witness has to say—a lot of it has nothing to do with the case or the questions,” Engoron told Kise. Moments later, Engoron repeated that sentiment.

“We’re not here to hear what he has to say, we’re hear to hear him answer questions, and most of the time he’s not,” Engoron said. That phrase seemed to particularly tweak Trump, who, during a lunchtime break, posted the first half of the quote to his Truth Social account, leaving off the rest of it.

Engoron’s combative attitude was a departure from his normal demeanor. In earlier portions of the years-long legal case, he was noticeably patient with Trump and his attorneys, who often were not cooperative with his orders. Through the first five weeks of the trial, Engoron had been far more likely to crack a goofy joke than raise his voice.

Trump, too, was in a foul mood from the moment he lumbered slowly into court Monday morning, trailed by an unusually large entourage of attorneys and security. His face was in an angry pout, and although he was initially subdued on the stand, it didn’t take him long to blow up—especially after Engoron repeatedly checked his rambling testimony. At one point, infuriated by Engoron’s refusal to accept that a vaguely worded disclaimer at the start of financial statements absolved Trump of any wrongdoing, the former president curled forward in a hunch, leaning into the microphone. With his voice rising to a pitch of genuine fury, Trump berated Engoron for having ruled before the trial even began that Trump had indeed committed fraud.

“He ruled against me without knowing anything about me, nothing about me, he ruled against me,” Trump said, jabbing his finger in Engoron’s direction, sounding very much like a man who was deeply hurt. “He called me a fraud, and he didn’t know anything about me.”

The fact that Trump once held the most powerful office in the land but now had to answer questions from New York AG Letitia James’ lawyers also clearly was eating at him.

“How do you rule [on] someone, and call them a fraud, someone who as the president of the United States, who did a great job?” Trump ranted. “There’s a terrible thing you’ve done, it’s a terrible thing you’ve done! You’ve believed this political hack back there, and it’s unfortunate!” Trump stuck his finger out at James, sitting in the front row.

By the time of Trump’s rant—he delivered a second one later in the afternoon—Engoron had told Wallace, the AG’s office attorney, that he would let Wallace take the lead on deciding whether Trump’s answers were appropriately responsive. Engoron scowled at Trump’s attacks on him but didn’t respond, and Wallace, from his lectern, smirked.

“Done?” Wallace asked.

“Done,” Trump muttered, and Wallace continued his questions.

For his part, Wallace seemed more than willing to let Trump vent. On several occasions, Wallace said he’d be happy to allow Trump’s off-topic testimony to remain in the trial record because, as he noted with a grin, “There’s a lot in there.”

Trump’s eruptions aside, it was other parts of his testimony that might offer the most consequential takeaways from his day in court. James’ office has accused of him of intentionally submitting fraudulent valuations of his assets to banks and insurance companies in order to obtain better interest rates and coverage. Bank and insurance company executives have testified that they indeed gave him better rates based on his fraudulent numbers. So it was particularly important that, on Monday, Trump acknowledged that he did play a role in coming up with the numbers his company submitted to banks.

“I would look at them, I would see them, and I would maybe on occasion have some suggestions,” Trump testified.

In his testimony—when he wasn’t complaining about how unfair he believes the case to be—Trump appeared to be trying to spin a complex and not entirely coherent story, alternately describing himself as an uninterested, high-level executive who thought the financial statements were unimportant, and as someone who was very sure that the statements were inaccurate because they didn’t show him to be wealthy enough. Neither tactic seemed very successful.

James’ office had finished questioning Trump by late afternoon and Trump’s legal team declined to cross-examine him—although they did bring up the possibility they might recall him as a witness later in the trial. Trump’s attorneys told Engoron that they plan to ask for a mistrial as soon as James’ team rests its case, which should happen on Wednesday or early Thursday, after testimony from the state’s final witness, Ivanka Trump.