This Era of Athlete Activism Is About to Collide With the Reality of the Beijing Olympics

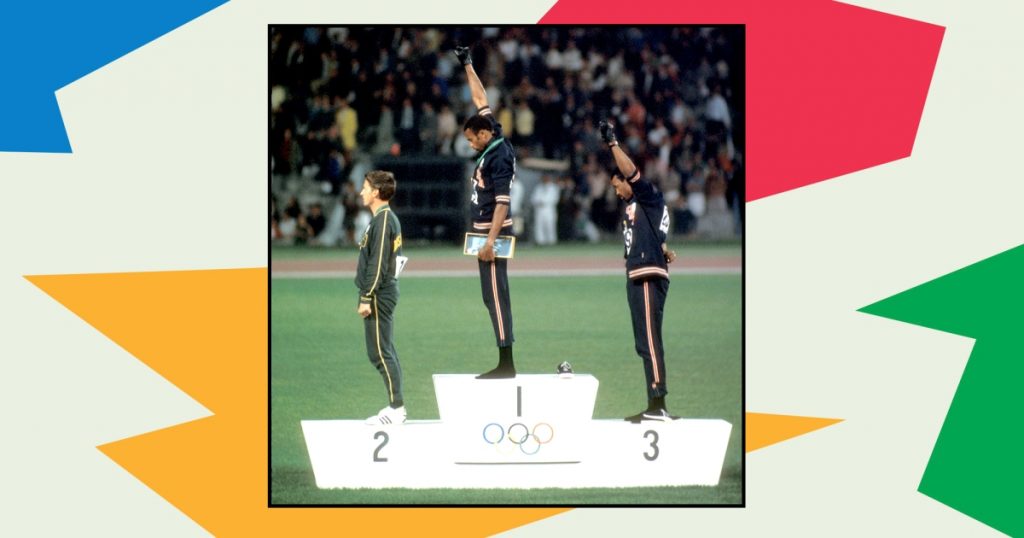

Mother Jones illustration; Rich Clarkson/NCAA Photos/Getty

Fight disinformation. Get a daily recap of the facts that matter. Sign up for the free Mother Jones newsletter.The Olympics is a showcase for the world’s best athletes, but it also serves as an unforgettable chance to capture the global viewing audience’s collective attention: Think of Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists in a Black Power salute after medaling at the 1968 Olympics, or long jumper Peter O’Connor climbing a pole and waving an Irish flag more than a decade before Ireland declared its independence from the United Kingdom.

These demonstrations have been iconic moments in Olympic history, despite the International Olympic Committee explicitly—and often laughably—undermining that legacy. This year’s Winter Olympics in Beijing, coming months after the IOC finally loosened its protest guidelines for athletes at the Tokyo Games, returns athletes and activists to a far more uncomfortable position—one that activists are likening to a climate of fear.

The ruling Chinese Communist Party is notorious for its harassment and detention of activists. “Anybody would feel unsafe in that situation,” said Pema Doma, campaigns director at Students for a Free Tibet, citing the Chinese government’s widespread use of surveillance. “It is the responsibility of the national Olympic committees to help the athletes process that fear and help them feel safe.”

Team Great Britain has done just that: British Olympic Association chief executive Andy Anson said last month that officials were “not going to stifle” athletes’ freedom of expression. But the United States, which announced a diplomatic boycott of the Games in December, has been far more circumspect. “It’s important for our athletes to understand we are a guest at their Games and we are under, and agreed to abide by, the rules of those organizations,” Sarah Hirshland, chief executive of the US Olympic & Paralympic Committee, said at a media summit in October. “We are absolutely making sure athletes understand the rules and laws of the country that we are going to and where those risks might be because those laws and rules are different than they are in our country.” The State Department has “repeatedly briefed US athletes about safety and security issues in China,” the Washington Post reported.

Yang Shu, a Beijing Olympics official, did nothing to dispel concerns about the rights of athletes when he told reporters last month that any expression “in line with the Olympic spirit” would be allowed, but behavior “against Chinese laws and regulations” would be punished.

Fear of the Chinese government has created a split among activists who vary in their support for demonstrations by athletes. “With no guaranteed protection by the IOC or the Chinese authorities, we strongly advise athletes not to speak up about human rights while in China,” the advocacy group Global Athlete, whose leaders include former Olympic and Paralympic competitors, said in a January statement.

Meanwhile, last week, Lhadon Tethong, director of the Tibet Action Institute, implored athletes to do the opposite. “Your silence is their strength,” she said at a press conference organized by Human Rights Watch. “You have to speak out against the wave of genocide.” Because China is not permitting spectators to attend the Olympics due to the coronavirus, the focus on athletes as instruments of activism has been even more pronounced.

Doma’s fellow activists, who are part of the larger #NoBeijing2022 coalition, met several athletes from Team USA and other countries while protesting at Olympic qualifiers in California and Wisconsin and at the X Games in Aspen, Colorado. She said they were visibly anxious about talking to protesters, even as some expressed sympathy and interest in learning more about China’s human rights record. “They would say cryptic things like, ‘I can’t speak with you,’” she recalled. “We are gravely concerned that there is some kind of effort trying to reduce the exposure that the athletes can get about human rights topics,” Frances Hui, a Hong Kong democracy activist who went to the X Games, said on a press call last week.

Not all athletes were as nervous. Snowboarder Shaun White, one of the biggest-name winter sport athletes of the past two decades, agreed to take a photo with a Tibetan American activist at an Olympic qualifier in California while she held up the Tibetan flag. At least two athletes from Western teams even told activists that they planned to skip the Opening Ceremonies of the Olympics “as their personal form of protest,” the Washington Post’s Josh Rogin reported.

Despite the climate of fear in Beijing, many activists do not expect a serious Chinese reprisal against an athlete who protests. Even Teng Biao, a human rights lawyer who was detained and beaten in advance of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, has urged athletes to speak out and argued that China would not risk the negative international reaction of openly detaining an athlete. “If an athlete remains silent, their conscience is condemned,” he wrote last month.

That stance has changed the minds of other activists like MacIntosh Ross, who studies the Olympics at the University of Western Ontario. “After Beijing 2022 organizers threatened athletes, I was originally against athletes protesting at the games, for their safety,” he tweeted this week. “After some insightful discussions with more experienced activists, however,” which Ross told me included Teng, “I’m confident that political speech and gestures won’t result in detention.”

What athletes are missing is any comprehensive display of support from the IOC, most national Olympic committees, broadcasters, and even event sponsors (who have been notoriously tight-lipped about China’s ghastly human rights abuses). The IOC’s discomfort with athlete activism extends back to Smith and Carlos’ famous salute in 1968, which led to them being ostracized for decades for defying the Olympic charter, which has in various forms throughout the years barred any “political, religious or racial” demonstration.

These rules changed in the run-up to the Tokyo Olympics, where several athletes took a knee amid a global reckoning over racial justice after the murder of George Floyd, but the IOC still only allows athletes to express their views while “respecting local laws.” This carve-out gives China ultimate influence over what it deems acceptable or not. The IOC had a chance to express some degree of concern for human rights when they held a virtual meeting with Doma and other #NoBeijing2022 activists in October. Instead, Doma says, they were told by IOC officials, “It is a very complicated world.”