The UAW Strike Brought Back Militancy and Won What Seemed “Impossible”

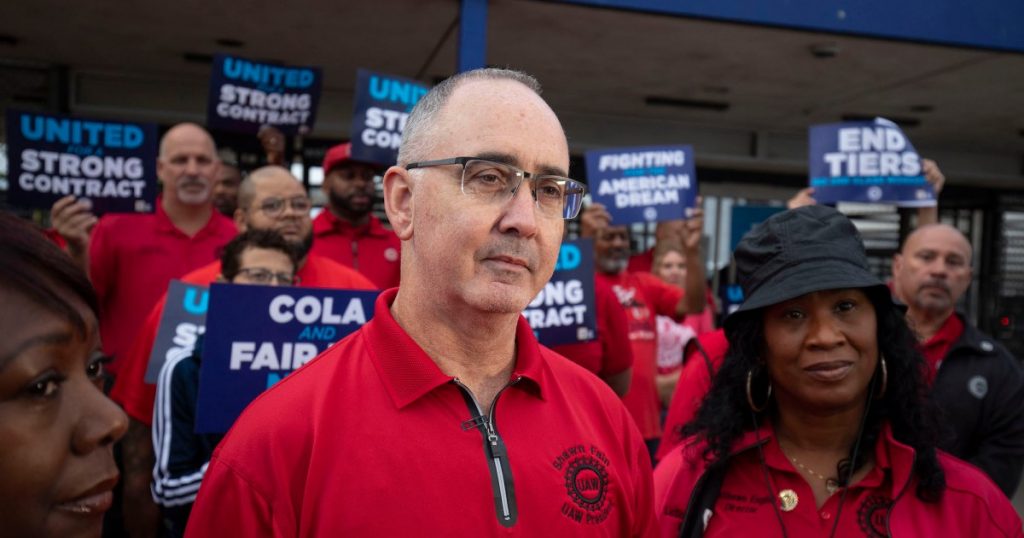

United Auto Workers president Shawn Fain with members at a Stellantis plant in Michigan in July. Bill Pugliano/Getty

Fight disinformation: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter and follow the news that matters.The United Auto Workers’ 46-day strike was meant to be a historic return, a path forward by embracing the union’s militant roots.

The name alone made that clear: UAW leaders called it “The Stand Up Strike,” a reference to the historic 1936 sit-down strike at a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan, that helped create the modern labor movement. The goals were similarly bold this time. The union was not only trying to win a record contract for members, but also signal to workers throughout the country that there is still strength in numbers and claims that labor’s best days will forever be behind it are a myth. The strike sent a message that the working class can still organize itself and demand—not plead for—what it deserves. That could be seen in how UAW President Shawn Fain treated the billionaires and CEOs atop our economy with unrelenting disdain as he refused to shake their hands, lambasted their greed with scripture, and mocked them with memes. In the end, Fain and his members won.

The strike came as the United States transitions to a new green economy that risks undermining protections for unionized workers. Fain made clear that does not have to happen, stressing that “corporate America is not going to force us to choose between good jobs and green jobs.” He has now backed that up by securing major concessions that would allow workers at Big Three battery plants to come under the UAW’s national agreements.

The historic strike has now been called off in the lead-up to members voting on whether to ratify the tentative agreements reached in recent days. The union has warned automakers that during the next round of contract negotiations in 2028 it will no longer be the Big Three, but the Big Five or Big Six, as manufacturing at electric car companies like Tesla increases. (Workers at Tesla’s Fremont, California, plant have now formed an organizing committee with the UAW that they hope will lead to unionization.)

For the first time in UAW history, the union was led by a president directly elected by members. Fain, a union reformer and former electrician from Indiana, came to power earlier this year on a mission to end what he saw as an overly comfortable relationship between recent union leaders—many of whom were implicated in major corruption scandals—and the Big Three.

We have a tentative agreement at GM.#StandUpUAW pic.twitter.com/UtaWZJurEW

— UAW (@UAW) October 30, 2023

Fain used the rhetoric of class war more fluently and to greater effect than almost any public figure in recent memory. In August, a month before launching the strike, Fain threw a contract proposal from Stellantis, formerly Chrysler, into the trash. He wore a t-shirt that declared “Eat the Rich” and vowed to “wreck” the economy of the “billionaire class.” He spoke movingly of keeping one of his grandfather’s UAW pay stubs in his wallet and read passages about the difficulty of the rich entering the Kingdom of God from a Bible given to his grandmother at an orphanage in 1933.

His well-heeled critics accused him of staging a months-long “Broadway play and nightmare.” They portrayed him as someone more interested in playing the role of an online class warrior than doing the hard work of negotiating a contract. Their critiques underestimated both him and the leftist union activists Fain relied on.

The contract, Fain and UAW leaders have told members, has major wins. The benefits workers will receive if they vote to ratify the four-and-half-year contract are myriad:

A 25 percent wage increase, including an immediate 11 percent jump upon ratification of the contract. (That is before including the additional gains that would come from cost-of-living adjustments.)

Starting pay would increase by about 70 percent—from about $18 an hour to more than $30 per hour—over the life of the contract after factoring in COLA benefits. That does not include overtime or profit-sharing payments.

The top rate for production workers would increase from $32 to $42 per hour.

The time it takes to reach the top rate would drop from eight years to three years.

Second-tier wages at places like Ford’s Rawnsonville, Michigan, components plant would be eliminated. As a result of that and the new three-year progression, some workers would immediately see their hourly pay go from about $19 an hour today to $35 an hour—the equivalent of a roughly $32,000 annual raise.

At Ford, 401(k) contributions would jump from $6,300 to $11,000 per year. (The union plans to unveil additional details about the agreements with Stellantis and GM later this week.)

Temporary workers with at least 90 days on the job would immediately become full-time employees. In the future, temps would be converted to permanent status after nine months. Some temps would see their pay increase by 168 percent by 2028. In total, it means they would make roughly $190,000 more than they would if their pay remained stuck where it is now.

“This contract is about more than just economic gains for autoworkers,” Fain said in a speech on Sunday designed to explain the agreement with Ford. “It’s a turning point in the class war that’s been raging in this country for the past 40 years. For too long, it’s been one-sided and working class people have been left behind. That’s why this contract is more than just a contract. It’s a call to action to workers everywhere to organize and fight for a better life.”

Fain used an approach that flipped the normal order of things, allowing the union to play the part of the companies’ disciplinarian. For the first time, the union struck all of the Big Three automakers at once. Workers did not all walk out on the same day. Instead, the union adopted the “stand up” strategy under which the strike gradually expanded in response to what was happening at the bargaining table. If Stellantis behaved well, Fain would announce that the company was being spared. If it was recalcitrant, one of its most profitable plants would be taken offline. By the end, about 46,000 of the 146,000 UAW members at the Big Three were on strike.

In another break from tradition, Fain used livestreams to tell members in real time just how much progress was being made in the negotiations. Members knew well before the tentative agreements were reached that their union leaders had secured major victories such as a newfound right to strike over plant closures and a restoration of the cost-of-living adjustments workers gave up to help the Big Three survive the Great Recession. The message was clear: Stay on the picket lines; the strike is working. This level of communication would have been unheard of under past UAW leadership. (Fain knew this well; he’d long fought against the undemocratic approach from the old guard known as the “Administration Caucus.”)

Fain described many of the victories won in the contract as having achieved the “impossible.” If ratified, the union will be able to launch company-wide strikes to prevent future plant closures by the Big Three. General Motors has agreed to have workers at its Ultium battery cell joint venture with LG come under the national agreement with the union. The UAW has secured a path to bringing workers at new Ford battery plants into the master agreement.

Fain told workers that the monetary value of the agreement with Stellantis is 103 percent greater than what the company was offering at the start of the strike. Earlier this year, Stellantis announced that it was idling its Belvidere, Illinois, plant, which employed about 1,300 people. The move was seen as a warning by Stellantis to the UAW about its ability to upend workers’ lives. As part of the negotiations, Stellantis agreed to reopen the plant and add more than one thousand jobs at a new battery plant there.

The UAW received an unprecedented boost from Joe Biden who became the first president in US history to join a union picket line last month. On Monday, Biden praised what he called the “historic agreement” reached by the UAW after speaking with Fain.

Union members will soon vote on whether to ratify these agreements. Fain has said he and UAW leaders “wholeheartedly endorse” the contracts, saying that they believe they have “squeezed every last dime out” of the companies. The ratification votes will be a referendum not just on the agreements, but on members’ confidence in Fain’s ability to get them the best possible deal.

In another sign of the UAW’s increased militancy, the union has arranged for its contracts to expire at the end of April 2028. That will allow the union to potentially begin its next strike on May Day, which traces its roots to American workers’ fight for an eight-hour workday. (The United States decided to celebrate Labor Day in September as part of an effort to distance itself from the more leftist holiday.) The UAW has invited other unions to have their contracts expire at the same time so that workers have the ability to strike across multiple industries in 2028.

“The autoworkers at Ford just won a major battle in the fight for a better world,” Fain said on Sunday. “Billionaires aren’t going to save the American dream. Working class people are saving the American dream. The UAW is saving the American dream. And we are doing it together.”

The next day, on Fain’s 55th birthday, the UAW called off the strike after reaching the final of the three tentative agreements with General Motors.

Editor’s note: The author of this post and other Mother Jones workers are represented by UAW Local 2103.