The Midterms Have the Power to Usher in an Era of Climate Action

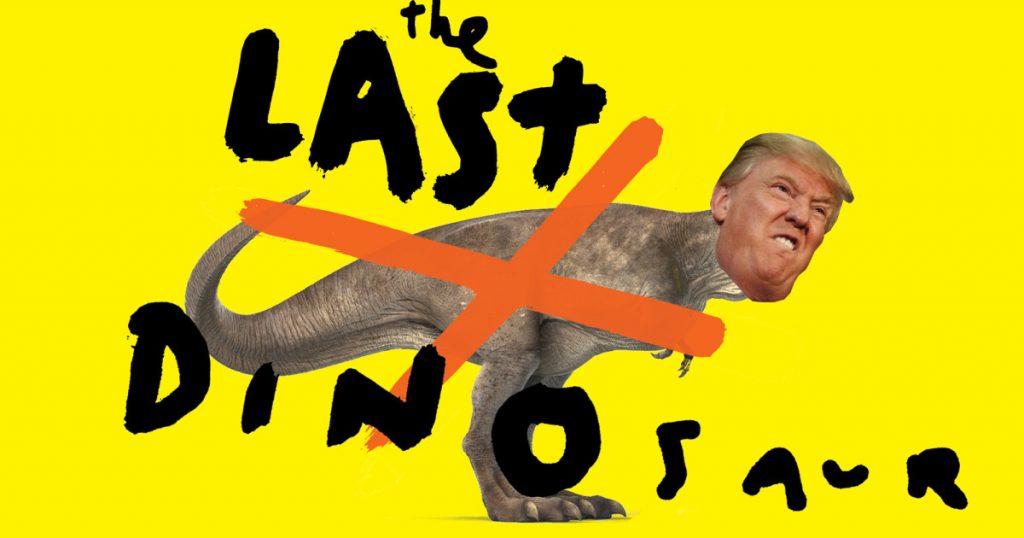

James Victore; Source: T-Rex: Turbosquid; Trump: Dominic Reuter/Reuters

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

Here’s the most important thing to know about climate politics in this critical election year: How fast we act decides the future we get.

Of course, climate politics seems to be about many things, things that this administration has been hell-bent on sabotaging: strong emissions rules, carbon pricing, fuel economy standards, international treaties, cuts to fossil fuel subsidies, and respect for science and scientists in federal decision making. Yet at its heart, climate politics is simple. It’s all about speed.

I don’t mean that the climate fight is urgent, though of course it is. I mean that the climate fight is itself a fight about tempo, about how fast high-carbon industries will fall apart. The question is not whether we’ll see bold climate action but when, and how much more it will cost us in blood and treasure if we wait.

That suggestion seems absurd to many Americans. Fossil fuels are everywhere in this country, and what is ubiquitous always feels permanent.

Action on climate is inevitable, and momentum is already far stronger than most of us understand.It’s not. Powerful forces strain against this status quo, and torque is building for a snap forward in climate action. November’s election, it turns out, could be the breaking point. To understand why, we must consider the shifting global politics of the climate crisis, the unprecedented acceleration of the clean economy, and the carbon bubble we live in.

Most Americans care about climate change. Many Americans know the climate crisis will only grow more urgent the longer we fail to act boldly to cut emissions. Many of us even recognize that as our scientific understanding of our planet’s climate and biosphere has sharpened, the anticipated consequences of failure have grown grim.

Indeed, the alarm calls seem to be working: Hundreds of thousands of people read an academic paper warning of a “Hothouse Earth” future—a nightmare future where melting permafrost, burning forests, and souring seas lead to a hotter and hotter climate, likely beyond the capacity of humanity to repair. This summer of megafires, heat waves, and freak storms seems to have driven home the warning. Americans are worried.

We think nothing’s being done, though. This is understandable, living, as we do, in the country with arguably the world’s least effective national climate policies, a nation run by a GOP that has made climate denialism practically an article of faith, with broadcast media outlets that rarely cover the link between climate change and extreme weather events. Heck, even the Democratic National Committee recently reversed its position swearing off fossil fuel money. From Washington, climate politics appeared to be a slag heap of failure even before Donald Trump took power.

Here, then, is the second thing you need to know about climate politics: Action on climate is inevitable, and momentum is already far stronger than most of us understand.

The planetary crisis driven by climate change threatens lives, livelihoods, and regional economies worth many times the value of the entire fossil fuel industry, and it threatens them existentially. The only true human analogue is war. Whole nations, huge and powerful industries, cultural and religious leaders, and hundreds of millions of ordinary people around the world see high-carbon industries as a threat to their highest principles and most fundamental interests.

If we don’t want to trigger planetary catastrophe, we’ll need to leave most of the world’s coal, oil, and gas unburned.And they have been taking action: the Paris accord and the Kigali agreement, the global divestment movement, the spread of carbon pricing mechanisms, legal cases trying to hold fossil fuel companies liable for the harm they’ve caused. Even here in the United States, the “We Are Still In” movement has gathered more than 3,500 businesses, city governments, and universities pledging to abide by the Paris accord. This summer, California became the second state to commit to 100 percent clean electricity by 2045. People are being drawn to action, and that action is already having effects.

We can judge those impacts by the swelling crowd of experts concerned about the “carbon bubble.”

The carbon bubble is the mismatch between the declared value of fossil fuel reserves (and thus of the energy companies that own them) and society’s willingness to suffer the consequences of burning those fuels. Put simply, if we don’t want to trigger planetary catastrophe, we’ll need to leave most of the world’s coal, oil, and gas unburned—indeed, climate policy is at its most fundamental core the question of how much we’ll leave in the ground.

If those fuels won’t be burned, they’re not worth much. But fossil energy companies are some of the world’s biggest companies precisely because they have these huge reserves, and these reserves are valued as if they will all be burned. That makes these companies not just overvalued, but massively overvalued. It makes fossil fuels a financial bubble, one that’s bound to burst.

The risks of the carbon bubble popping and triggering a global financial crisis are serious enough that some of the world’s largest financial institutions (including the national banks of England, France, and the Netherlands, the World Bank, and the Financial Stability Board) have begun looking at ways to avoid a repeat of the 2007 subprime crisis.

When the carbon bubble pops, the ability of fossil fuel industries to set political agendas will be deeply compromised. Like many bubbles, this one will pop not when it physically can’t go on, but when profits no longer look certain. The world doesn’t even have to achieve bold action to pop the bubble. Simply the loss of confidence in the ability of fossil fuel companies to develop and profit from their reserves could cut the companies’ worth enough to guarantee those assets become “stranded.”

Here’s the third thing you need to know: The clean economy is getting exponentially more competitive.

The next decade is lining up to be a golden age for sustainable innovation, entrepreneurship, and civic leadership. Just 10 years ago, talk about “decarbonizing” the economy was aspirational—going carbon-zero was a goal toward which we were moving, not a capacity we possessed. Clean energy was too expensive. Energy efficiency technologies were too limited. Batteries and electric vehicles were too constrained. Green building was seen as too esoteric. Green urbanism was too controversial. Climate restoration of natural systems was too theoretical. Sustainable design was in its infancy.

Ten years, it turns out, can change everything. We now live in an era when the costs of clean energy drop almost every year. When battery innovations have drastically improved, and electric vehicles look primed to crash through the automotive industry. When superinsulated, green homes are about as cheap to build as conventional structures. We already live in the last decade’s fantasies of what sustainable innovation might one day be like.

Clean energy and batteries, in particular, are on steep learning curves. As we build more, the price drops; as the price drops, the number of situations in which wind and solar outcompete coal and gas grows. It took humanity all of history to install the first terawatt of wind and solar energy. Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates the second terawatt “will arrive by mid-2023” and be 46 percent less expensive than the first one. Follow that sort of learning curve through another doubling (from two terawatts to four), and it will be cheaper to build and run wind and solar plants than to continue running existing fossil fuel power plants. There will literally not be a business case for burning coal, oil, or gas to generate electricity.

The Trump administration and the GOP Congress are vital to slowing action on climate.The clean economy will eventually put the dirty economy out of business—but just how soon is the crux of the climate fight.

The carbon lobby’s agenda is not to win—few investors seriously think fossil fuels are in for boom times ahead—but to lose slowly, to stall for time, to maintain the appearance of unshakable ubiquity (and thus profitability).

Looking at the building global political momentum on climate, the growing competitiveness of the new economy, and the rising financial risks facing fossil fuel companies, we begin to see just how vital the Trump administration and the GOP Congress are to slowing action on climate. They (and Russia) are working as essentially the only strong counterforce to rapidly accelerating climate action. They are the core constituency for predatory delay.

Their power to delay, though, is fragile—and this November’s election could break it. If the American people send a Congress to Washington that’s ready to challenge the president’s stall tactics, that Congress could, of course, undo much of the damage of the last two years. But more importantly, the very election of that Congress would send a global signal that the United States will no longer be the land of delay and denial—a signal that climate action has not been checked, that clean economy acceleration will continue, and that now would be a great time to get your money out of high-carbon investments.

The tide of climate politics could turn on such an election. Indeed, we may soon be able to look at these years as the high-water mark, when a flood of greed and insanity crested, stopped, and rolled back faster than we ever imagined possible.