The Chilling Story of Three Women Haunted by the Same Rapist—And How the Law Failed Them

Mother Jones illustrationSomething about the sound of the knock at the front door made Mary-Scott Hunter think a neighbor was in trouble. She had just arrived home from her job at a corporate training company, and she was mulling over an earlier fight with her girlfriend, but the knock jolted her out of it: five loud, fast raps. She didn’t recognize the two men she could see looming through the window, dressed in oddly formal clothing. When she cracked the front door, they identified themselves: a Minneapolis police officer and an FBI agent.

Oh shit, Hunter, now 54, thought. What have I done wrong? She wasn’t sure if she should open the door. She didn’t trust cops all that much. She let them in but remained standing, uncertain, as they settled into in her living room.

The men asked Hunter if she had been raped in 1987. Yes, she said.

They told her they had identified the stranger who broke into her house when she was 21 years old and attacked her in the hallway outside her bedroom. The suspect’s name was Darrell Rea. After 31 years, he was in custody.

First came the shock. Then relief—and, finally, happiness. “Seriously?” she asked.

Sergeant Chris Karakostas, a homicide investigator at the Minneapolis Police Department, assured her it was true. He asked her if she wanted to sit down, so she did, and she listened.

From the perspective of police, Hunter had done everything right back in 1987. She’d immediately called the cops, allowed a nurse to collect a rape kit, and recounted the attack in painful detail during multiple police interviews. But the rape had taken place four years before the state forensics lab began using DNA to help local investigators solve crimes, and Minneapolis police leads went nowhere. The case went dormant. For decades, Hunter lived with the uncertainty of whether her rapist was still out there. (Hunter’s story first came to our attention through Mother Jones Editor-in-Chief Clara Jeffery, who became friends with Hunter in the years after the attack.)

“I think it was the first time that I started to just be a little bit more in my body. And that was the start”—she pauses, searching—“of not wanting to be in my body.”In the years before and after Hunter’s rape, generations of city police had investigated Rea for different crimes. They had come to believe that the former apartment building caretaker could be linked to a number of sexual assault, physical assault, murder, and missing person cases, according to a criminal complaint. But he had never been convicted of serious charges.

Then, in a breakthrough in 2013, the state crime lab matched DNA from Rea, by then in his late 50s, to the 1983 murder of a 17-year-old, Lorri Mesedahl. The teenager appeared to have been raped and then beaten to death near railroad tracks in north Minneapolis. But because the murder was so old, many witnesses were dead, and prosecutors wanted more than the DNA match from Mesedahl’s body to charge Rea with murder, says Hennepin County Attorney’s Office spokesperson Chuck Laszewski. So investigators ramped up their testing of old Minneapolis rape kits. That’s when a hit came back on Rea for Hunter’s 1987 attack. Many of the details in Hunter’s case were different from the other crimes police suspected Rea of committing—indicating that his modus operandi might be broader than they thought.

By the time the investigators told Hunter about Rea in March 2018, she had given up hope the case would ever be solved. “I stopped fantasizing about this guy getting caught a long, long time ago,” she says.

Today, Hunter’s experience—the knock at the door, the detective bearing unexpected news—is becoming less of an extraordinary occurrence. After decades of shelving untested rape kits, and otherwise mishandling many reports of sexual assault, police departments are now more likely to make progress on cold-case rape investigations, due to unprecedented political will, new investigative techniques, and increased funding for DNA analysis.

In Michigan, for instance, longtime Wayne County prosecutor Kym Worthy’s effort to test about 10,000 rape kits since 2009 led to the identification of at least 833 suspects who could be linked to multiple sex crimes. In Cleveland, a state-funded effort to test old rape kits and hire new investigators and prosecutors has produced about 370 convictions since 2013. And a $38 million grant program created by the Manhattan district attorney’s office paid for the testing of 55,000 rape kits across the country from 2015 to 2018—eliminating or nearly eliminating the pileup of untested rape kits in seven states.

More than 20 states have passed a cascade of laws in the past few years requiring mandatory testing of old or new rape kits, audits of untested evidence, or notification systems for survivors to keep track of their kits, according to the Joyful Heart Foundation, an organization that advocates for sexual assault survivors. Meanwhile, police departments are rapidly adopting new approaches to solve sexual assaults, including genetic genealogy, a technique that relies on DNA profiles available in consumer databases and was used to catch the alleged Golden State Killer last year.

Despite these sleuthing advances, a group of survivors is still precluded from getting justice in the legal system. As Sergeant Karakostas explained to Hunter as he sat on her couch that March day, the window for her to press charges had long passed. At the time the attack occurred in 1987, Minnesota’s statute of limitations for criminal sexual offenses involving victims over 18 was just three years.

“I would love nothing more than to be able to stand in front of [him],” she says, “to be like, ‘Yep. Guess what? I’m here. Giving you a little bit of payback.’”Statutes of limitations exist to protect defendants from false charges based on faded memory or degraded evidence. But they can also be a way for rapists to remain free in a criminal justice system that convicts assailants of a felony in just 5 out of every 1,000 rapes, according to estimates from the anti-sexual violence organization RAINN. Their lengths for sex crimes vary widely between states. Over the past couple of decades, often following cultural upheavals like the Catholic child abuse scandal and the #MeToo movement, activists across the country have fought to abolish or lengthen statutes of limitations. They’ve seen mixed success—often meeting resistance from civil liberties advocates concerned about the risks of wrongful conviction, as detailed in an expansive New York Times investigation into the movement to abolish statutes of limitations.

At present, at least seven states have no statute of limitations for any felony sexual offense. Dozens of others, including Minnesota, have lengthened the time given to prosecutors to bring charges, or added exemptions for cases with DNA evidence. “The more we understand about trauma, and about how these kinds of offenses happen, the statute of limitations slowly catches up to those understandings,” says Lindsay Brice, law and policy director for the Minnesota Coalition Against Sexual Assault. Still, these reforms don’t apply to anyone whose case expired before the new laws took effect—Hunter included.

Unlike rape, there is no statute of limitations for murder in Minnesota. So in 2017, after four years of follow-up testing to the 2013 DNA match, Hennepin County prosecutors charged Rea with killing Mesedahl. And Sergeant Karakostas hoped Hunter would play a role in putting him away. Despite some key differences, certain similarities between her rape and the murder could help prosecutors prove the charge in court, if a judge accepted that the cases were sufficiently alike. So before he left Hunter’s living room, Karakostas asked if she would help them.

Hunter instantly agreed. Taking part in the murder trial could be a way to recover some of the feeling of control wrested from her three decades prior. She’d never really forgiven herself for giving up that control, even though there was nothing to forgive; even though she knew, intellectually, that the rape was not her fault. “The idea of being able to prosecute—or be involved in a prosecution—was part of that want to be able to do something positive, to enact a result,” she tells me.

She pauses for a moment. “Dude should pay,” she adds.

The investigation that led officers to Hunter’s front door was long and circuitous. Minneapolis police had been looking into Darrell Rea for more than 40 years, uncovering a lineup of women and girls they believe suffered at his hands: a terrified child, a troubled teenager, a marginalized sex worker. Each case proceeded in fits and starts, hindered by problems common to sexual violence investigations—witnesses dropping out, bias against certain types of victims, and, yes, expiring statutes of limitations. (Through his lawyer, Rea broadly denied the criminal accusations against him and declined to answer specific questions or comment further on the allegations detailed in this article.)

In 1990, the Minneapolis Police Department got the call that would eventually prove crucial in bringing Rea to justice. Seventeen-year-old Victoria Owczynsky—or Vicky O, as police investigators have long called her—was reported missing after disappearing on August 26, 1990. In a photograph circulated in a missing person bulletin, she smiles broadly, wearing a baggy sweatshirt and big earrings; permed, dark hair frames her face in a cloud.

According to retired Minneapolis Police Sergeant Tim Opdyke, who later picked up the investigation, the first sergeant assigned to Owczynsky’s case believed “maybe she disappeared voluntarily on her own,” he says. “You know, 17 years old. She just ran away.” But it was hard to square that with the fact that Owczynsky had left behind her money and cigarettes—an odd choice for a teenager planning to skip town.

At the time she disappeared, she’d been staying with a friend, Naomie Rondo, in northeast Minneapolis. Rondo was one of Rea’s two stepdaughters. A neighbor told a police officer he had seen Owczynsky sitting in Rea’s pickup truck on the day she vanished.

By this point, Rea was not a stranger to police. In 1977, he had been charged and tried for first-degree criminal sexual conduct. A jury acquitted him of that charge but convicted him for simple assault, landing him in jail for a short time.

Some 11 years later, police got a report that Rea was abusing his stepdaughters. Rondo, now 45, says Rea would fondle her—washing her or tickling her, or else putting a hand down her pants while she was sleeping. At least once, he locked her out of the room and assaulted her older sister, Monique Stevens, while Rondo pounded on the door, crying. Stevens, now 48, has a vivid memory of looking at her second-grade teacher and wondering if she should tell her how Rea pressed his body onto hers. I better not, she thought. She didn’t tell anyone for years, while Rea was entering her room at night, progressing from fondling her to raping her, punching, choking, and hitting her head against the headboard. She says she believed that if she let it happen, he wouldn’t hurt her mother or siblings; that if she was quiet, her family could stay together. Only later, when Rondo reported the abuse to her school in the late 1980s, did police become aware of the allegations.

But after investigators questioned the girls, the family stopped cooperating with law enforcement, according to Karakostas. While prosecutors can press child sex abuse charges without the consent of a parent or guardian, they must think they can meet the legal burden of proof to move forward. Once the family pulled out, neither of the two Hennepin County prosecutors who reviewed the case would bring charges.

Monique Stevens and Darrell Rea

Courtesy Monique Stevens

Monique Stevens, Naomie Rondo, and Victoria Owczynsky Courtesy Monique Stevens

Stevens tells me she used to babysit Owczynsky, who was a few years younger and often stayed at their house. She says Owczynsky was the only person who directly witnessed Rea raping her.

Police working the Owczynsky missing person case searched Rea’s home and car in 1990. When officers interviewed Rea, he denied that Owczynsky had gotten in the truck with him, Karakostas says. They never found enough evidence to arrest him for the girl’s disappearance.

But over the years, the Vicky O case would bring Rea under the police department’s scrutiny time and time again. More than a year after her disappearance, Sergeant Opdyke and his partner, Sergeant Phil Hogquist, picked up the Owczynsky file from a box of unsolved cases. They, too, became fixated on Rea, who was by then in his late 30s, living and working as a caretaker in a shabby northeast Minneapolis apartment building. When they brought him in for questioning, Opdyke remembers thinking Rea was unnaturally calm under stress, and that he was using the interview to get information from the investigators. “By the time the interview was over, I was flat-out accusing him of the murder of Vicky O, and he never reacted,” Opdyke says. “Never once got upset. He was there to find out what we knew.”

While Opdyke was convinced then that Rea was guilty, prosecutors weren’t. Opdyke says he was told that without a body, or more concrete evidence, they could not press charges.

But there was, possibly, another way to get to Rea. Given the 1977 assault case and the report regarding his stepdaughters, it seemed likely that they were dealing with a repeat offender. To that end, Opdyke and Hogquist learned from a fellow investigator of yet another case Rea might be involved in. In 1988, a 23-year-old homeless sex worker named Barbara Briggs had been attacked under circumstances that were similar to the details alleged in Rea’s 1977 trial. That case had gone cold, but it had one crucial difference from the other incidents: DNA evidence.

Briggs was walking to a White Castle one early morning in June 1988 when a man flashed money at her from a silver station wagon. They drove to a parking lot near some railroad tracks, had sex, and then, Briggs tells me, “he wouldn’t stop.” A judge would later find that the man strangled her “to continue the sexual intercourse.” She fought back—“scrapping and scrapping, just kicking and fighting and punching and kicking,” Briggs says. One of her hits must have drawn his blood; it dripped onto her shirt. Then, the man jammed a tool resembling an ice pick into the hollow at the top of her neck. The blow, somehow, didn’t kill her. Briggs was able to escape by playing dead.

Police would later test the bloodstain left on her shirt for protein and blood type—DNA testing was not yet available—and rule out the first person they arrested for the attack, according to the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office. Then they let the case languish. “It sat on somebody’s desk, or got passed around,” says Hogquist, who recalls feeling frustrated that there was a broad tendency to neglect sexual assault cases in the department. It was even worse for sex workers, another investigator tells me. “Society was like that back then,” says Briggs, who is now 54 and works as a nurse. She doesn’t think attitudes have changed. “Put yourself in harm’s way? That’s what you get.”

But by 1993, five years after the attack on Briggs and three years after the disappearance of Owczynsky, the state crime lab had started testing DNA evidence. A Minneapolis police lieutenant working with Opdyke and Hogquist drafted a search warrant for Rea’s DNA. They obtained a sample and compared it to the old bloodstain from Briggs’ shirt.

It matched.

Yet when the investigators brought Briggs’ case to prosecutors shortly afterward, they were rebuffed: The three-year statute of limitations was already up for both rape and attempted murder. While Minnesota had enacted a law in 1991 that extended the prosecution window to seven years for most criminal sexual offenses, it only applied to new cases, or cases in which the statute of limitations had not already run out. Briggs’ case had expired less than seven weeks before that law was enacted.

Not until a couple of years ago did anyone tell Briggs about Rea. At first, she says, she was glad—“but then I thought, There ain’t nothing I can do about it.” It’s just one more way in which she feels like the legal system failed her. “As violent as a crime like that, they should never have a statute of limitations. It’s ridiculous.”

For Opdyke, Hogquist, and the other investigators, the dead end in Briggs’ case deflated their hopes of catching Rea. “That’s where all our investigation ended,” says Hogquist. “We got shot down.” The Owczynsky investigation, too, went quiet.

When Opdyke retired in 2006, he made a copy of the Vicky O files to take with him to Florida. “That was a case we carried with us when we left,” he says. Thinking about Rea still gives him “goosebumps.”

“It was like the one who got away. I always thought we had the right person, but we—meaning [Hogquist] and I, and the police department at the time—were never able to do anything about it.”

It would be almost 20 years before the Minneapolis Police Department would make significant progress in their investigations of Rea. Again it’d be because of Victoria Owczynsky, the 17-year-old who had been friends with his stepdaughter.

Owczynsky, or her body, still had not been found, but in late 2007, Sergeant Gerry Wehr came across her missing person case. He was on light duty at the time, recovering from hip surgery, with an assignment to look for cold cases that showed promise. Wehr says he liked reading files from the crammed archives stashed in the clock tower of Minneapolis’ City Hall, retracing the steps of old investigations. “It’s dusty, dirty, it’s kind of dark, and there are just boxes everywhere,” Wehr says. “Of course, nothing’s in order.”

His interest had been piqued by the Owczynsky case after police got a call reporting that a relative of Owczynsky’s was using her information to get welfare benefits. So box by box up in the clock tower, Wehr continued working the case for years, learning about the teenager’s disappearance, and about Rea, and, eventually, Briggs. With the help of the FBI, he started developing a criminal profile of Rea, uncovering several other attacks, mostly on sex workers, that seemed to fit his modus operandi. Over and over, those cases had been dropped, or not charged in time. Sometimes there was simply not enough evidence. But other times the reason was bad police work, Wehr admits; in particular, cases that involved victims who did sex work tended to languish.

The haphazardly stored, garbled archives made progress slow. It took nearly five years of investigating before Wehr pulled a crumpled piece of paper out of a box: the search warrant for Rea’s DNA from Briggs’ case. Wehr had long been hoping for DNA evidence to help his search; techniques for genetic analysis had rapidly advanced since Owczynsky disappeared, and DNA would likely be the key to moving any cold case forward. Wehr knew his discovery meant Rea’s DNA sample, as well as the blood from Briggs’ shirt, could still be in evidence. Maybe they could be retested, Wehr thought. Maybe he could discover a new match, a new connection to Rea: “I just knew there would be something that would come up if we entered it in the system.”

Both samples, it turned out, were still in storage. So in 2013, the state crime lab used updated DNA testing techniques to confirm that the 1993 sample from Briggs’ bloody shirt matched Rea’s DNA, according to Laszewski, the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office spokesperson. Then the lab uploaded the modern DNA profile it had developed from the bloody shirt into a database for crime scene evidence. That’s when the system returned another, unexpected hit: semen recovered from the autopsy of Lorri Mesedahl, the 17-year-old killed 30 years earlier.

“I was actually surprised [there] was only one” match for Rea in the database, Wehr tells me.

Mesedahl’s murder was not one of the cases Wehr had pegged for Rea. One Friday night in early spring 1983, after returning home from a party, Mesedahl had snuck out to go see her boyfriend. When she arrived at her boyfriend’s grandparents’ house close to 3 a.m., his grandmother refused to let her in. The next morning, her body was found, face-down, surrounded by a pool of blood, next to railroad tracks. Semen was found in her vagina and rectum, as well as on the legs and seat of her pants. But the attack took place before the advent of DNA forensics. Not until 2008 would the samples be tested and uploaded into the system.

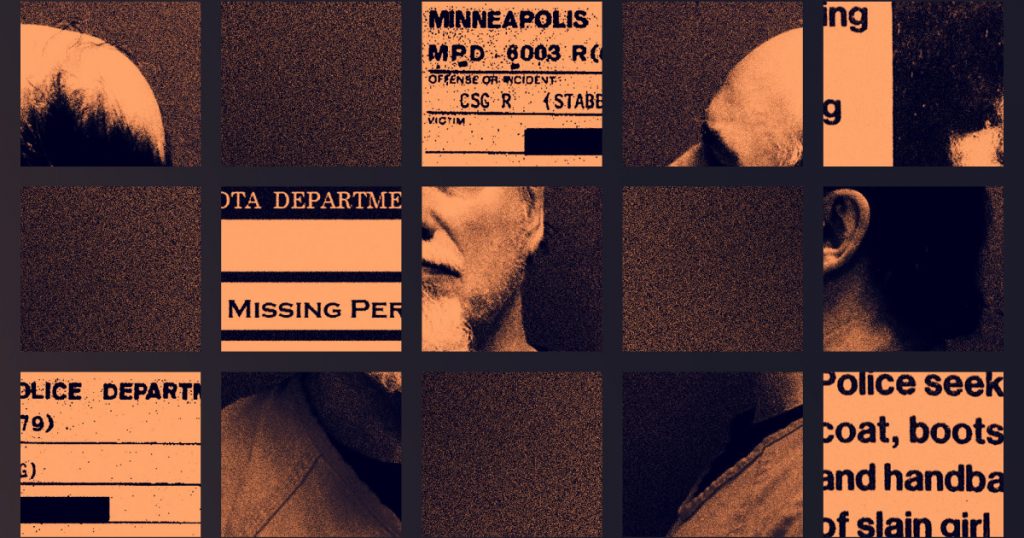

A Minneapolis Star Tribune story on Lorri Mesedahl’s murder in 1983

Star Tribune/Newspapers.comWhile the Owczynsky case had never yielded any kind of DNA evidence, and the charging window on Briggs’ case had expired, the Mesedahl case blew the entire investigation into Rea wide open: There was DNA and the statute of limitations on murder would never expire. Finally, police had discovered evidence with a real chance of convincing Hennepin County prosecutors to bring charges.

When Wehr retired and handed the case off to Sergeant Karakostas, he says he told him, “You know, when you arrest him, you got to make sure he’s getting charged. Because people have been doing this just to him for 20 years. He gets called in on a rape, he gives them a story, and they threaten him and yell at him they’re going to charge him, he’s going to prison. But nobody ever does. He walks away.”

In part to see if other cases could be linked to Rea, investigators started checking old untested rape kits, according to Laszewski. By 2015, they had found one more victim: Mary-Scott Hunter, a young legal assistant who was raped in 1987.

In March that year, Karakostas, by then the lead investigator on the Mesedahl case, believed he finally had enough evidence and arrested Rea. But he says prosecutors “got cold feet.” Laszewski says the county attorney’s office felt it needed more evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Rea had murdered Mesedahl. Key witnesses had died, including the medical examiner who inspected her body. So, as Wehr had predicted, Rea denied everything in an interrogation and was released.

It would take another two and a half years and follow-up testing on Mesedahl’s clothes before prosecutors decided they were confident enough to pursue the case, Karakostas says. In September 2017, Rea was taken into custody again, and was charged with second-degree murder.

Mary-Scott Hunter was always a light sleeper, even on the nights she had been drinking. In 1987, she was 21 years old, working at a law firm and sharing a split-level duplex with three friends from Carleton College. “We were all incredibly close,” says Nina Levine, who lived upstairs. They bonded over the Grateful Dead and played softball together.

They were somewhat worried about Hunter, who was somewhat worried about herself. She had recently dropped out of school and was struggling. “Maybe not eating enough,” Hunter says. “Drinking too much.” She was trying to change those parts of her life. One Thursday night in March, she relapsed, going out drinking at a bar, binging and purging, then falling asleep in her bedroom on the bottom floor of the duplex.

Around 4:30 in the morning, a noise woke her up. Then she heard it again, louder. She rolled out of bed and left her room to check on her friends. That’s when she saw the man at the top of the staircase. He wore a dark sweatshirt, the hood pulled tight around his face, Hunter would tell police after the incident. In his right hand, he held a screwdriver.

“Don’t freak out,” he said, according to her police report from that night. “I just want to fuck you. If you freak out, I’m going to stab you.”

He forced her to the lower-level landing. Then he raped her for more than 30 minutes.

“I was convinced, at one point, that somebody in the house would hear it, and the cops were going to come,” Hunter says. But they didn’t. As the man grew frustrated, she thought, I’m going to die. She was stunned when he finished and left without killing her.

She immediately woke up Levine, who helped her call the police. When officers arrived, Hunter tells me, “it just got surreal. It was a relief that they were there, but they were very nonchalant about the whole thing.” Levine remembers watching an officer question Hunter and sensing he didn’t believe her, as if she had invited the man to her house after going out drinking that night. “She was shaking a lot,” Levine remembers. “She would start to talk, then get a little silent, then go back.”

Hunter recalls the lingering surprise that she hadn’t been murdered. She remembers cracking jokes in the back of the police cruiser with Levine and another friend who accompanied her to the hospital. During her rape kit exam, a nurse wrote that Hunter was “quiet, cooperative.”

Only later, as she waited in the hospital lobby for a ride back to the house, did Hunter allow any darker emotions to hit her. She leaned forward in her chair and stared at the floor. “I can’t believe this happened,” she recalls saying out loud. Levine put a hand on her back.

“I’m not typically somebody who kind of breaks down, so it wasn’t that,” Hunter recalls. “I think it was the first time that I started to just be a little bit more in my body. And that was the start”—she pauses, searching—“of not wanting to be in my body.”

Nina Levine and Mary-Scott Hunter

Courtesy Nina Levine

The duplex, as it looks now, where Hunter lived when she was attacked in 1987

Photo by Mary-Scott Hunter

A few days later, when Hunter sat down with a Minneapolis police sergeant for an interview, he asked her what she was wearing when she was raped, according to a transcript of their conversation. She answered his questions simply and completely. She wanted to help. When the sergeant identified a suspect and put together a lineup, she was frustrated with herself when she couldn’t identify him. (Forensic testing eventually ruled that suspect out.) After the lineup, Hunter remembers, the investigation seemed to fizzle.

At the same time, she and her roommates were struggling to cope with what had happened. In the following weeks, Hunter slept on a mattress in their living room. She read and re-read feminist literature, and signed up for self-defense classes with Levine. The landlord fixed the window locks, installed an alarm system, and offered them free therapy sessions with her husband, a psychologist.

As months passed, then years, Hunter’s struggles with mental health got worse, and, eventually, better. She got sober; she came out. “I got to know myself,” she says.

As she aged, she thought about the attack, and the still-open investigation, less and less. Yet for decades, she continued to question whether she had done enough to stop the rape. Those doubts still nag her: “Why the hell didn’t I do more to fight?” she asks. “Is that some deficiency in me, that I clam up when I’m in ‘flight or fight’? Why did I do the things I personally did? Did I not think I was worth fighting?”

She knows it’s not her fault she was raped, knows it’s never any survivor’s fault. But knowing is a different thing than feeling it.

Only after Sergeant Karakostas knocked on her door last year, after prosecutors finally decided to charge Rea, did Hunter come to a kind of peace with her doubts. Rea had killed before, she knows now. On the night he’d attacked her, the same could have happened to her. “Maybe I actually did have the right instincts,” she says now. If she had fought back, she might not have survived. “It’s let me off the hook a little.”

Seventeen days before Rea’s trial was scheduled to begin this February, he waived his right to trial by jury—leaving the verdict completely in the hands of Hennepin County Judge Tamara Garcia. In coming to her ruling, Garcia agreed to consider evidence not just from the killing of Mesedahl, but also from the 1988 attack on Briggs, which the judge determined was similar enough to Mesedahl’s case that it could corroborate the facts of the murder.

But Hunter’s rape, Garcia decided, couldn’t factor into her verdict. While some elements of the rape were similar to Mesedahl’s murder, the attack had taken place in Hunter’s house, not Rea’s car, and did not leave her with serious visible injuries. The allegations of sexual abuse against Stevens and Rondo would also not be considered. None of those crimes, Garcia ruled, shared enough details in common with the murder to be included in her deliberation.

Hunter was crushed by the news that her case wouldn’t be considered. She’d been holding out hope that the trial would give her a chance to do something, to act, finally, after years of stasis. She wouldn’t be afraid to take the stand, or to see Rea across the courtroom. “I would love nothing more than to be able to stand in front of [him],” she says, “to be like, ‘Yep. Guess what? I’m here. Giving you a little bit of payback.’”

Neither Hunter nor Stevens attended any of the hearings in the lead-up to Garcia’s verdict. But Briggs did. Seeing Rea in person for the first time since the attack, she noted he’d changed physically; his hair was gone, and he’d gained weight. “But inside of me says, ‘Oh, that’s him,’” Briggs tells me. “Same eyes. It doesn’t matter if he was 500 pounds.”

“I was held captive by him, and there was nothing I could do,” she tells me through tears. “I would like to see him have to stay in there until he dies. Because I’ve been in prison for almost my whole life.”On May 1, Judge Garcia convicted Rea of second-degree murder with intent. In an order explaining her decision, Garcia wrote that “the DNA evidence in this case is compelling” and that a guilty verdict is the “only possible conclusion.” While Rea’s public defender had tried to propose other potential perpetrators, none of the alternate theories added up. Rea, Garcia noted, “generally denied ever having raped anyone, but admitted that he had gotten into fights with women ‘usually after’” his “one-night stands” or encounters with sex workers.

Rea, who is now 64, will be sentenced on June 25. Under Minnesota’s 1983 sentencing guidelines, he faces a maximum of just over 10 years, though Garcia could give him more if she decides “substantial and compelling” aggravating factors are present. With “good behavior” and the time he’s already served, he could be released in just over five years, even if he gets the maximum.

If the statutes of limitations on Hunter’s and Briggs’ rapes had not expired, and Rea was also found guilty for those crimes, his recommended sentence could have been more than double the time—up to 21 years—calculates Mike Brandt, a Minnesota criminal defense attorney who is not involved with the case.

There is some hope that this generation of sexual violence survivors will be the last to face the obstacles presented by statutes of limitations. Minnesota long ago extended the three-year prosecution window that applied to the kind of attacks survived by Hunter and Briggs to nine years, and it eliminated the ticking clock on any sexual assault involving DNA evidence. But in the past two legislative sessions, state lawmakers have rejected proposals—including one from now-US Rep. Ilhan Omar, a former state legislator—to completely abolish the statute of limitations on sexual assault cases. At a hearing for one of the measures in May, state Sen. Ron Latz argued that such a change would set a “dangerous precedent” of pursuing cases that could “destroy the life of the accused,” according to the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

The way the system currently works, “the only person we’re protecting is Darrell Rea,” Sergeant Karakostas tells me. Hunter, Stevens, and Briggs all said they wished the law treated rape the same as murder. “Having statutes of limitations for these sexually violent crimes is belittling and demeaning,” Levine wrote to me recently. The law “basically says, after X amount of years, the crime and its impact don’t matter anymore.”

Hunter is still living with that impact. Some nights, half-awake, she hallucinates the sound of someone coming up the stairs in her house. The night terror loops until she wakes herself up screaming. “Closure,” she says, “is kind of a tricky word.” When Rea’s sentence comes down, “I can’t say I’ll be happy if it’s maximum. But I’ll be at least not really, really angry.”

Similarly, Stevens says she was “so relieved—like I could breathe for the first time in my life” when she heard about the conviction. But she also worries about Rea’s sentence. It’s not that she’s afraid to see him; she’s seen him once as an adult, at her grandmother’s funeral a few years ago. It’s that there are so many ways—PTSD, struggles with intimacy—that her childhood experiences still remain with her. “I was held captive by him, and there was nothing I could do,” she tells me through tears. “I would like to see him have to stay in there until he dies. Because I’ve been in prison for almost my whole life.”

“I don’t think that man should see another day of life,” adds Briggs. Thinking back to the night she was attacked, “I was ready to just die, you know,” she says. “I was letting go because I was exhausted. But I think the good Lord wanted me to survive. To press charges for Lorri Mesedahl.” Mesedahl is buried a few blocks from Briggs’ home. She visits the gravesite often.

Karakostas still isn’t done with the case. He believes Hunter’s rape, with its differences from the other attacks, indicates there could be more to uncover. “I think any investigator who worked, even touched this case, or knows anything about it, would agree that the probability that there are other victims out there, either living or dead, is probably pretty good,” Karakostas tells me. Now that Rea has been convicted of murder, he will be legally obligated to hand over a new DNA sample. And unlike the bloodstain from Briggs’ shirt, this one will be uploaded to the FBI’s national database. From now on, it will be automatically compared to unknown DNA from crime scenes across the country. When Rea’s DNA enters the system, Karakostas will be waiting to see if more hits come back from cases outside Minnesota. One day, he speculates, there could be another prosecution. In that future case, a judge could rule that the experiences of Hunter and Stevens count as corroborating evidence. Maybe they could still get some kind of day in court. “There’s a lot of women out there that really don’t have some justice for what happened to them,” Karakostas says.

There’s also still the big unanswered question: What happened to Vicky O? Over the years, rumors of where she may be have circulated in the police department. According to multiple investigators, the apartment building where Rea lived at the time Owczynsky disappeared in 1990 had an underground level, and at least one witness told the cops that he used to spend time down there. Over the years, it’s become the stuff of legend among certain Minneapolis police officers that Owczynsky’s body might be buried underneath the building.

One problem: The city of Minneapolis condemned the building and tore it down in 1992. In its place: the headquarters and parking lot of the Minneapolis Police Department’s 2nd Precinct.

It’s a chilling prospect, that the body they’ve spent decades looking for could be literally underneath their feet. “Theoretically,” Karakostas muses, “you’d have to take [the building] down.” He isn’t ruling it out. Like the investigators before him, he’s still driven by the search for Vicky O, and Rea is still his number-one suspect. “No matter what it took,” Karakostas says, “nothing would please me more than to find Vicky.”