The Beltway Sniper Is Now the Center of a Debate About Juvenile Lifers

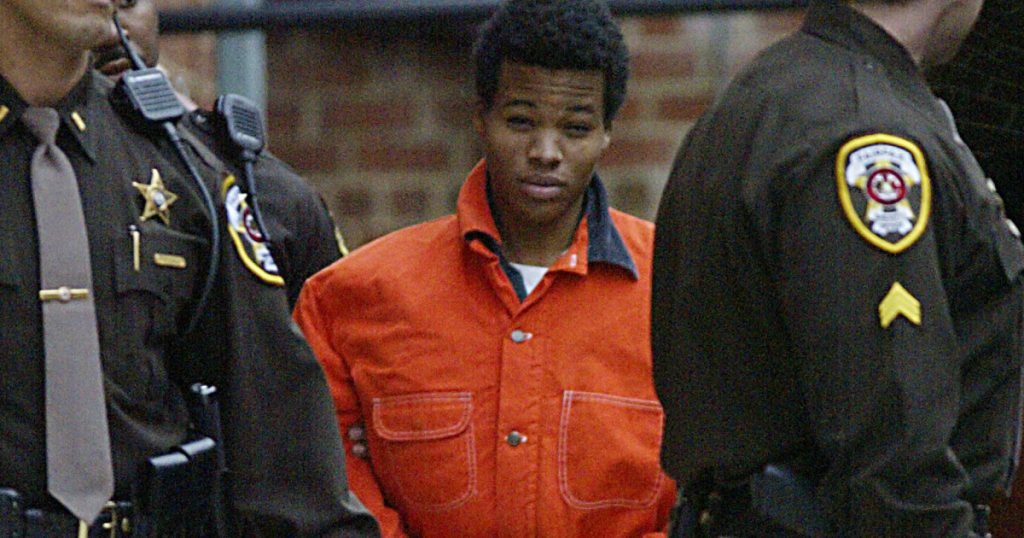

Lee Boyd Malvo leaves a pretrial hearing in Fairfax in December 2002 Luke Frazza/AFP/Getty Images

Lee Boyd Malvo was only 17 when he stepped into a blue Chevy with his 41-year-old mentor, John Allen Muhammad, and launched a shooting spree that terrorized the greater Washington, DC, area for three weeks in 2002. Over multiple attacks, the pair gunned down more than a dozen innocent civilians—people pumping gas, mowing the lawn, shopping, or reading on a park bench—leaving 10 dead and wounding others.

The random nature of the shootings, known as the Beltway sniper attacks, fueled anxiety around the region. Pedestrians changed their walking patterns out of fear of being targeted, and gas stations put up tarps to shield drivers filling their tanks. Police officers eventually arrested the shooters while they were asleep in their car, where law enforcement found binoculars, walkie-talkies, and a hole cut in the trunk to fire bullets through. Investigators tied the pair to at least 11 prior shootings from Washington state to Alabama. Muhammad was later executed, and Malvo was ordered to spend the rest of his life in prison.

Malvo’s case could offer a chance of release for about a dozen other Virginians who committed murders as teenagers.Today, Malvo is a 34-year-old living out his term at a remote supermax in Virginia. He has said that he hopes his victims and their families can someday forget about him. But 17 years after the rampage, his case will get renewed attention next month at the Supreme Court: The younger Beltway sniper is now at the center of a debate about the ways teenagers are punished for crimes, and the extent to which states must give juvenile lifers—even those who committed notoriously violent offenses—an opportunity to show they have changed since youth.

If the court rules in Malvo’s favor, Virginia could be forced to resentence him. It is unlikely that he will ever be allowed out of prison, since he’s serving a total of 10 life sentences. But his case could offer a chance of release for about a dozen other Virginians who committed murders as teenagers. And depending how broad the Supreme Court’s decision is, it could pave the way for juvenile lifers elsewhere to petition for shorter sentences too, says Jody Kent Lavy, the executive director of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, which filed a brief supporting Malvo.

Malvo was born in 1985 in Kingston, Jamaica. His father moved away five years later, and his mother beat him regularly, according to court documents. At the age of 15, while he and his mom were living in Antigua, he met John Allen Muhammad, an African American Army veteran from Washington state who knew his mom. Muhammad had recently lost custody of his three children, and had fled with them to the island, where he made a living selling forged US identification documents. When Malvo’s mom moved to Florida, Malvo stayed behind and grew closer with Muhammad, who began introducing the boy as his own son. In 2001, Muhammad returned to the United States with Malvo, who briefly joined his mom in Florida, and a court returned Muhammad’s three kids to his ex-wife.

John Allen Muhammad at trial in 2003

Lawrence Jackson-Pool/Getty ImagesMalvo soon fled to Washington state to be with Muhammad, and they lived in a homeless shelter. Muhammad, furious with the courts for barring him from his own kids, began plotting a harebrained scheme to get them back by gunning down random civilians in order to try and convince the government to give him millions of dollars to create a utopia for black children. He trained Malvo to carry out the attacks, with daily shooting lessons at a gun range that sometimes lasted 12 hours. Malvo was so distressed he attempted suicide.

But after the pair carried out the crimes and were arrested, Malvo remained loyal. He tried to protect Muhammad by exaggerating his own role in the Beltway killings, falsely claiming that he pulled the trigger every time. He showed little remorse, laughing and pointing to his head as he described to investigators where a bullet hit a woman at a Home Depot in Virginia.

The United States is the only country where minors can legally be imprisoned for life without parole. For decades, courts in some states were even required to hand down this punishment to young people who committed serious crimes like murder. But in 2012, citing research on brain development, the Supreme Court ruled that mandatory life-without-parole sentences were unconstitutional for teenagers, who were still growing and possessed so much capacity for change. Even if a kid was convicted of homicide, the court ruled in Miller v. Alabama, a judge had to consider factors such as their maturity level and home environment when deciding a punishment. Four years later, the Supreme Court clarified that its ruling was retroactive, and that states would need to consider granting more than 2,000 juvenile lifers around the country new sentences. Life without parole, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, should be reserved for only the “rarest of juvenile offenders…whose crimes reflect permanent incorrigibility.”

But the state of Virginia has resisted resentencing Malvo. His attorneys argue that because his lack of maturity and rough childhood played a key role in his crimes, and because a court never took these factors into account, his punishment should be revisited.

By 2012, when the Supreme Court made its landmark ruling outlawing mandatory life-without-parole sentences for teens, Malvo had been imprisoned for a decade, and he’d begun to express regret for the horrific crimes. “I was a monster,” he told the Washington Post in an interview that year. An investigator told reporters he had been under Muhammad’s spell and was now more mature. “The spell was starting to wear off at trial, and now that he’s in jail for his entire life he’s probably being more realistic about what Muhammad did and didn’t do,” retired FBI agent Brad Garrett, who had questioned Malvo after the arrest, told the Post in 2012. “He’s older, and he understands now how impressionable he was.”

Since the Supreme Court rulings, more than 1,700 juvenile lifers nationally have had their sentences shortened, either by lower courts or state legislatures. More than 500 juvenile lifers have been released. But the state of Virginia argues that Malvo and about a dozen other juvenile lifers should not be resentenced because, like several hundred juvenile lifers nationally, they are serving discretionary sentences, not mandatory ones.

At the time of Malvo’s trial, Virginia required juries to hand down one of two punishments to anyone over the age of 16 who committed capital murder: the death penalty, or life without parole. Malvo’s attorneys argue that because the jury could not offer a shorter sentence, it did not actually have much choice. And they add that in any case, even if Malvo’s punishment was technically discretionary, he should still be resentenced because the court did not consider his age, lack of maturity, and home environment the first time around, nor did it consider whether any of these factors might warrant a lesser punishment. “Such a life-without-parole sentence violates Miller whether it is ‘mandatory’ or not,” they wrote in a brief to the Supreme Court.

The case, which the court will hear on October 16, could help resolve a disagreement among states about how to treat lifers serving discretionary sentences. In Virginia, a federal appeals court sided with Malvo last year, prompting the state to appeal to the Supreme Court. The state’s highest court ruled in a similar case that people with discretionary sentences should not be resentenced. Elsewhere, while a majority of states have moved away from life-without-parole punishments for teens, 15 states have filed an amicus brief siding with the state of Virginia in Malvo’s case.

“Whether life without parole is the appropriate punishment for Malvo…is potentially a thorny question. But it is not the question presented here.”Some advocates worry the notoriety and severity of Malvo’s crimes will work against him, and that the court, now stacked with more conservative members, could use the case to buck earlier trends of granting more leniency to juvenile offenders. But Malvo’s attorneys emphasize that the issue in front of the Supreme Court next month is not whether Malvo should ever be released from prison, but whether lower courts should be required to at least consider age and maturity levels while sentencing people who committed killings as teens. “Whether life without parole is the appropriate punishment for Malvo—taking into account his youth at the time of the crimes, his vulnerability to Muhammad, whom he thought of as his father, and his capacity for change—is potentially a thorny question,” his attorneys wrote in a brief to the court. “But it is not the question presented here.”

One of the dozen or so Virginia lifers whose future hangs in the balance is Holly Landry, who was 16 in 1996 when she and four others beat a man to death with a hammer during a robbery. Landry, who had no prior criminal record, said her accomplices threatened to hurt her if she didn’t help. (Her 35-year-old co-defendant, who testified against her for a reduced sentence, according to her attorneys, is set to be released in 2027.) A forensic psychologist at the time concluded she was immature for her age, and that neglect as a child made her susceptible to being pressured by her older co-defendants.

In the two decades since, Landry has earned her GED in prison, held a job, and started a support group for young offenders, even after developing multiple sclerosis. “Far from ensuring that only the rare, irreparably depraved minor is sentenced to imprisonment for life without parole, Virginia’s sentencing scheme has imposed that penalty in every case of which we are aware involving a juvenile convicted of capital murder,” her attorneys, one of whom also represents Malvo, wrote in court documents in her case. Landry, they added, “was not one of the ‘rare’ juvenile offenders for whom rehabilitation was impossible.” If the Supreme Court sides with Malvo, she could have an opportunity for a shorter sentence.

“The children who commit crimes like this, children who commit first-degree homicide, are almost always severely damaged children,” says Kathleen Wach, an attorney representing Derek Ray Jackson Jr., another juvenile lifer in Virginia. “People who are severely damaged do not deserve to be locked up for the rest of their lives. We owe it to them to look at what happened, to look at what brought them to this place, and devise a sentence that takes into account their situation.” Wach, who was raising her own kids in the DC area during the Beltway sniper attacks, says the shootings are still “seared into my memory.” But Malvo didn’t act alone, she says, and he was still just a teenager.

Last year, the judge who sided with Malvo was less sympathetic. But he wrote that the Supreme Court’s prior rulings left little doubt that children should not be sentenced as harshly as adults. “To be clear, the crimes committed by Malvo and John Muhammad were the most heinous, random acts of premeditated violence conceivable, destroying lives and families and terrorizing the entire Washington, D.C. metropolitan area for over six weeks,” Judge Paul Niemeyer wrote, barely stifling his own opinions about the case. “But Malvo was 17 years old when he committed the murders, and he now has the retroactive benefit of new constitutional rules that treat juveniles differently for sentencing. We make this ruling not with any satisfaction, but to sustain the law,” he continued. “As for Malvo, who knows but God how he will bear the future.”