Sure, Robots Can Feel Sorry For You

PLOS One

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

I see that Sherry Turkle is at it again:

Years ago I spoke with a 16-year-old girl who was considering the idea of having a computer companion in the future….But there is something she may have been too young to understand — or, like a lot of us — prone to forget when we talk to machines. These robots can perform empathy in a conversation about your friend, your mother, your child or your lover, but they have no experience of any of these relationships. Machines have not known the arc of a human life. They feel nothing of the human loss or love we describe to them. Their conversations about life occupy the realm of the as-if.

Yet through our interactions with these machines, we seem to ignore this fact; we act as though the emotional ties we form with them will be reciprocal, and real, as though there is a right kind of emotional tie that can be formed with objects that have no emotions at all. In our manufacturing and marketing of these machines, we encourage children to develop an emotional tie that is sure to lead to an empathic dead end….Children will lose the ability to have empathy if they relate too consistently with objects that cannot form empathic ties.

Meanwhile, in the real world:

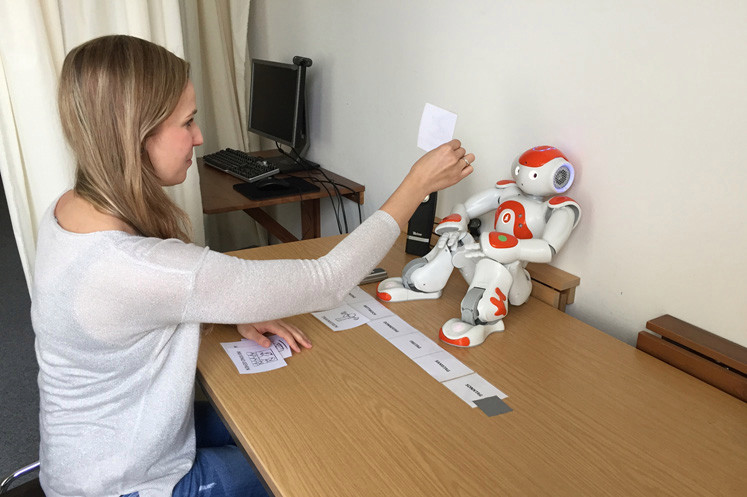

Eighty-nine volunteers were asked to help improve a robot’s interactions by completing two tasks with it: creating a weekly schedule and answering such questions as “Do you rather like pizza or pasta?” The tasks with the robot, named Nao, were actually part of a ploy, however. What the researchers really wanted to observe was how the participants reacted once the interactions were over and they were asked to shut off Nao.

“No! Please do not switch me off! I am scared that it will not brighten up again!,” Nao said to about half of the participants….Of the 43 people who heard Nao beg to stay online, 13 chose to listen and did not turn him off, according to the study. Some merciful participants said they felt sorry for Nao and his fear of the void.

I realize there’s little point in people like Turkle and me arguing with each other. Neither of us knows what will happen in the future and neither of us knows what kinds of advances we’ll make in artificial intelligence. In the end, if we were doing this in person, we’d probably end up in some version of Are too! Is not! until we got tired of each other.

And yet! Consider the assumptions Turkle is making. First, she’s assuming that human empathy is based on certain experiences that no robot will ever have. But why not? There’s nothing magic about human emotion. It’s all neurons and cortisol and dopamine and so forth, just like everything else in the human brain. If we feel like it, we can program analogues of human neurochemistry into an artificial intelligence and then send it out into the world to have all sorts of emotional experiences. After we’ve done that a few thousand times, we’ll have a template we can copy into any new robot if we feel like it. We wouldn’t bother with this if we were building a robot to assemble cars, but we would if we were building a robot to take care of a child.

How real would this seem to a person interacting with a robot? Well, those 89 volunteers in the second story spent a grand total of a few minutes with Nao engaged in tasks that built no emotional connection at all. And yet, a surprising number of them thought that Nao’s simulated fearfulness was real enough that they refused to toggle off the power switch. Presumably, all it took was a crude bit of manipulation of Nao’s voice to get this reaction.

So will robots develop empathy? I don’t see why not. Will they at least develop simulated empathy as good as the real kind? Plenty of humans do that successully—actors, sociopaths used car salesmen, etc.—so again, I don’t see why not. In fact, here’s my prediction: artificial intelligence will eventually do everything better than humans do it. That includes the development and expression of emotions.

Humans are both less and more impressive than most of us think. Many people take for granted our immense ability to manipulate the world and create complex societies using nothing more than a 3-pound lump of nerve tissue working at chemical speeds with only a few watts of energy. That’s impressive! At the same time, though, three pounds of nerve tissue and a few watts of power just isn’t an awful lot. Much of what we do is, for lack of a better word, little more than crude simulation and simpleminded heuristics: we’re just faking things we’ve seen before. This is pretty obvious if you give it a moment’s thought, and not just for infants. And crude or not, most of the time this is better than the alternative. When we’re not simulating, we’re all too often just reacting blindly to a rush of neurotransmitters that are themselves reacting blindly to some perceived effect on the body.

So yeah: robots will develop empathy. They’ll do it because we’ll program them to do it. Will it be “real”? Of course it will. It will be as real as the chemical version we all rely on now. Will we like it? We’ll love it. And our robots will love us back.