SCOTUS Ducks High School Diversity in Admissions Case

Justice of the Supreme Court Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito attend a private ceremony Justice of the Supreme Court Sandra Day O’Connor before public repose in the Great Hall at the Supreme Court in Washington, Monday, Dec. 18, 2023.Pool Via Cnp/CNP via ZUMA

Fight disinformation: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter and follow the news that matters.The Supreme Court on Monday declined to take up a bombshell case challenging an admissions policy at a magnet high school in Virginia that was designed to increase racial and economic diversity at the school. However, Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas issued a strong dissent, signaling their willingness to embrace a radical view of racial blindness in school admissions. With more cases challenging admissions policies aimed at growing diversity making their way to the Supreme Court, the justices could still limit efforts to increase diversity in K-12 education in the future.

Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, one of the most prestigious public high schools in the country, adopted a new system for admissions in late 2020, shifting from a reliance on standardized tests to a more holistic review of applicants with reserved spots at all the middle schools that feed into Thomas Jefferson. The new policy was challenged by a group of parents called the Coalition for TJ, who claimed that the new policy was a form of anti-Asian discrimination aimed at lowering the number of Asian-American students who made up a majority at the school.

The new policy, like the old one, did not take race into account. It was not only race-neutral but race-blind, which is to say admissions officers do not know the race of the applicants. The group of parents was represented by the Pacific Legal Foundation, a libertarian non-profit law firm already representing Asian-American parents in two similar cases concerning public school admissions.

Last summer, the Supreme Court effectively banned affirmative action in university admissions, rolling back decades of precedent. The Thomas Jefferson case would have taken the court’s hostility to policies promoting racial equality to a new, more radical level. “The goal of the Pacific Legal Foundation and others in this extreme colorblindness movement is to take racial justice off the table as an objective for policymaking at all levels of government,” says Sonja Starr, a law professor at the University of Chicago who has closely followed the foundation’s cases, told Mother Jones last year. If the Supreme Court adopts this view, she warned, “it would be a legal earthquake.”

As I reported last August:

This next phase targets admissions policies in K-12 schools, and is an effort to maintain the status quo, even as American public education grows increasingly segregated. Radically, the lawyers driving this test case have invited the Supreme Court to go beyond its rejection of affirmative action and ban admissions policies that do not actually take race into account.

“If the government is simply choosing a race neutral policy in order to achieve a racial result, we are going to object,” explains Joshua Thompson, who leads the Pacific Legal Foundation’s education litigation. “You cannot have a racial purpose consistent with the equal protection clause,” Thompson argues, except “to remedy past government discrimination.”

If the court accepts that argument, it would constitute a sea change—not just in education, but in broader American life. For decades, public officials have considered racial disparities and segregation in arenas as varied as education, pollution, and health policy to be problems government should tackle. Under PLF’s theory, even the desire to eliminate racial gaps could be successfully challenged in court.

Alito makes no secret of why he would have wanted to take this case. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled in favor of the new admissions policy, he wrote, “is flagrantly wrong and should not be allowed to stand.” Justice Thomas signed onto this dissent.

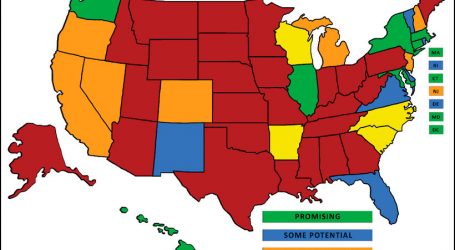

It’s possible other justices are sympathetic to Alito and Thomas’ view but didn’t want to take up a second case on race and admissions so soon after their major decision against affirmative action last year. If that’s the situation, similar cases in Maryland and New York working their way through the courts would allow justices to radically restrict efforts to integrate K-12 schools and restrict the government’s effort to promote diversity and equality. When the Supreme Court allowed Thomas Jefferson’s new policy to take effect at the start of the litigation, Justice Neil Gorsuch showed a willingness, alongside Alito and Thomas, to halt the new policy. Chief Justice John Roberts has authored opinions hostile to the idea of integrating K-12 schools—all evidence that there may be enough justices eventually to take up this issue.

The dissent appears to support the argument that the new policy takes away spots from deserving Asian-American students and gives them to less-deserving non-Asian students—though there is no data to support that conclusion. In fact, in the first class admitted under the new admissions policy, the average GPA of the incoming class was higher than in recent years under the old plan. In one paragraph that is likely to draw attention, Alito employs a hypothetical about Black basketball players to illustrate his view that the policy is denying admission to those who deserve it most.

Suppose that white parents in a school district where 85 percent of the students are white and 15 percent are [B]lack complain because 10 of the 12 players (83 percent) on the public high school basketball team are [B]lack. Suppose that the principal emails the coach and says: “You have too many [B]lack players. You need to replace some of them with white players.” And suppose the coach emails back: “Ok. That will hurt the team, but if you insist, I’ll do it.” The coach then takes five of his [B]lack players aside and kicks them off the team for some contrived—but facially neutral—reason. For instance, as cover, he might institute a policy that reserves a set number of spots on the roster for each of the middle schools who feed to the high school.

Alito’s point here is that the school board instituted a policy that may appear to be neutral on its face but still contained the insidious purpose of targeting a specific racial group, and therefore amounted to unconstitutional discrimination. The court’s decision not to take up this case allows Thomas Jefferson High School’s policy to stand, and signals to other schools and colleges around the country that race-neutral alternatives to affirmative action are permissible—at least for now.