Post-Roe, We Need Physicians to Advocate for Abortion Care

Where Do We Go From Here? is a series of stories that explore the future of abortion. It is a collaboration between Mother Jones and Rewire News Group. You can read the rest of the package here.

In late May, the Boston Globe broke the story of Kate Dineen, who was 33 weeks pregnant with a fetus that had a severe stroke in utero. Doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital refused to provide her a legal abortion under Massachusetts law, which does not allow most abortions after 24 weeks’ gestation.

Instead, Massachusetts General chose to refer Dineen to an out-of-state clinic, even going so far as to set up the appointment for her. Dineen paid $10,000 out of pocket and drove 500 miles for the procedure, the Boston Globe reported.

Massachusetts General Hospital is part of Mass General Brigham, a nonprofit network of hospitals that comprise some of the wealthiest and most venerable names in health care, including Brigham and Women’s Hospital. In the first quarter of 2022, the network grossed $4.1 billion in operating revenue.

Most individual abortion funds operate on a massively smaller budget. The gross income of the National Network of Abortion Funds in the entire fiscal year 2020 was just over $11 million.

Today, clinics provide the overwhelming majority of abortion care in the United States—close to 95 percent as of 2017. While clinics have many advantages, such as being able to keep costs down and streamline safe, outpatient procedures like abortion, their position outside major hospital networks has left them vulnerable to the overwhelming stigma, violence, and legal costs associated with providing abortion care in the country.

So what, if anything, can hospitals do now that Roe is dead? And how can physicians—arguably the most powerful health-care workers in the hospital system—be a part of that change?

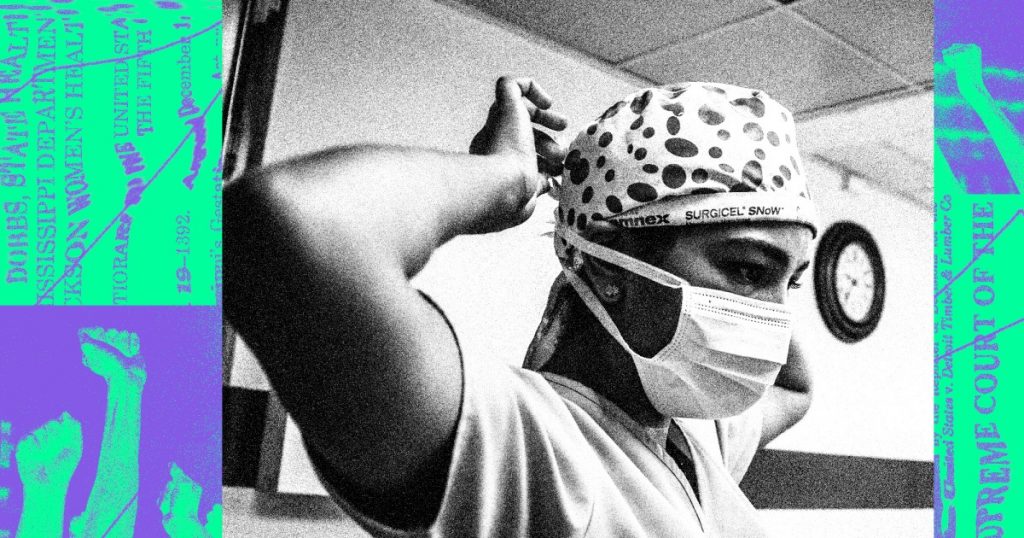

Dr. Deborah Bartz, an OB-GYN and board-certified specialist in complex family planning at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, divides her time between patient care and research. In her capacity, she provides abortion care and also trains the next generation of physicians in abortion care.

We chatted the week before the Supreme Court overturned Roe about how flagship research hospitals like Brigham and Women’s might expand abortion care to signal their support for that care to the public, and physicians have a role in pressuring their hospital systems for systemic policy change.

“It really hamstrings us to just talk about academic clinicians when honestly, all physicians have a stake in this, and all physicians can and should put more skin in the game, which includes private, non-academic OB-GYNS,” Bartz said. “It also includes internal medicine doctors, emergency medicine doctors. I honestly think that I put the responsibility more on individual physicians than I do on hospital systems.”

Bartz said all physicians—regardless of the kind of hospital they work in or their specialty—need to make a concerted effort along three fronts: “Become more informed and talk openly about abortion, become more knowledgeable about pathways into abortion care, and consider providing abortion care themselves.”

All physicians can “improve the referral lines, the quality of referrals to get patients into abortion care,” Bartz said. So, for example, “if a patient is in any practice—an internal medicine practice, an emergency medicine visit, what have you—and has an unintended pregnancy and is seeking abortion services, all physicians can and should become better informed about accessing abortion services specific to where they practice,” Bartz said.

In other words, physicians should not be discharging abortion seekers to Google. Rather, they should be equipped with an up-to-date knowledge of clinics in their area, relevant legal restrictions, and so forth.

Bartz practices in a state where Medicaid, as well as most private insurers, covers abortion care. However, when I asked her about the relatively higher cost of hospital abortions, especially when dealing with an un- or underinsured population, she stressed the importance of people donating to abortion funds.

Shifting the needle for systemic change in hospital policy requires physicians—a highly paid, powerful labor group that nonetheless has never been unionized—to have a plan for how to engage with administration. Dr. Alhambra Frarey, an OB-GYN at Penn Medicine, told Rewire News Group that “meeting with health system administrators and using statements of support from professional [medical] organizations is a good place to start.”

Similarly, Bartz said sharing patient stories with administrators is one step to create change from the bottom up. Frarey also suggests “organizing a diverse group of physicians from different areas of practice” to drive home to administrators that abortion care is not an issue narrowly affecting only family practice and OB-GYN departments.

But what policies should physicians attempt to change? Frarey’s recommendations for physicians looking to leverage their unique privilege within hospital systems focused on putting pressure on restrictive abortion care policies, hiring more abortion providers, and providing financial assistance to patients.

For example, some hospitals allow abortions to be performed only for maternal or fetal health indications, even when state law would allow abortions for any reason.

Frarey suggested expanding services to reflect the limits of the law in such cases.

But even when hospitals provide care to the limits of the law, they may not have a sufficient number of abortion providers to meet demand, and those providers in turn may not have dedicated time in the operating room. Frarey noted that hiring more abortion providers in hospital settings, ensuring those providers have dedicated operating room time, and then “expanding [that] OR availability in anticipation of an influx of patients from restricted states,” would all work together to meet the needs of patients now that Roe has fallen.

As far as funding abortion care, she suggested that hospitals in Hyde Amendment states, “establish an affordable cash package rate for services.” Hospitals, of course, are not going to want to provide services at a loss. Frarey said physicians could work with abortion funds and hospital administration to establish funding streams for affordable abortion services. Hospitals could then take at least some of the caseload off already overworked clinics.

A practicing emergency physician in the Bay Area working at a nonacademic hospital articulated a sense of powerlessness among many physicians to leverage their labor power collectively, due to the way that their training teaches them to show up “even when working conditions are dangerous or unhealthy” for themselves or for patients. Their name has been withheld for privacy reasons.

“Maybe I should be willing to lose my job. I can get another job,” they said.

The “culture of medicine,” they pointed out, teaches physicians that they do not hold the power to collectively influence a system within which they nonetheless wield immense individual power. But that power will be needed now more than ever.

Practically, the physician stressed the need for emergency departments to prepare for the “worst case scenarios” that family care physicians and OB-GYNs consider extremely unusual, such as botched mechanical abortions and complications from medication abortion.

“That’s really my job, to anticipate the worst-case scenario, and then I can manage anything else,” they said before Roe was overturned. “It may not be common after Roe falls that we see complications from self-managed abortions coming into the emergency department,” they insisted, but uncommon “is not zero.”

The physician said that currently, emergency physicians are primarily tasked with managing ectopic pregnancy, which is when a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus. One avenue to expand care is for emergency physicians to broaden their training to include more education in miscarriage management and manual uterine aspiration (MUA). Physicians, the anonymous physician suggested, could work with administrators to provide abortion care within the emergency department whenever legally possible.

Asked about the role of large research hospitals and whether they bear a particular responsibility in the current ecosystem of reproductive health care, they said, “I do think it would be incredibly helpful for big academic centers to publicize their support of abortion care. These centers are the ones publishing studies and establishing new guidelines of care nationally for all fields of medicine. So, just in the way we look to them to say what’s the most up to date treatment for an aortic valve replacement, having them state that they publicly support abortion care as good, high-quality care for patients, that would be very powerful and empower all hospitals to follow suit.”

The medical-legal environment after Roe is still murky, particularly around issues like the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) and the extent to which the Biden administration might choose to penalize hospitals that do not provide lifesaving abortion care to the full extent of the law. As Bartz pointed out, hospitals are not the optimal setting for most abortion care—in an ideal world, clinics would handle the bulk of patients, while hospitals took care of medically complex, resource-intensive cases only. But we do not live in that ideal world. As wait times at clinics across the nation increase, every health care setting must do what they can.

One thing appears certain: While it is neither practical nor helpful to move the majority of abortion care back into a hospital setting, hospitals and the physicians who work in them cannot allow clinics and abortion funds to continue shouldering the social, legal, medical, and financial burden of this fight alone.