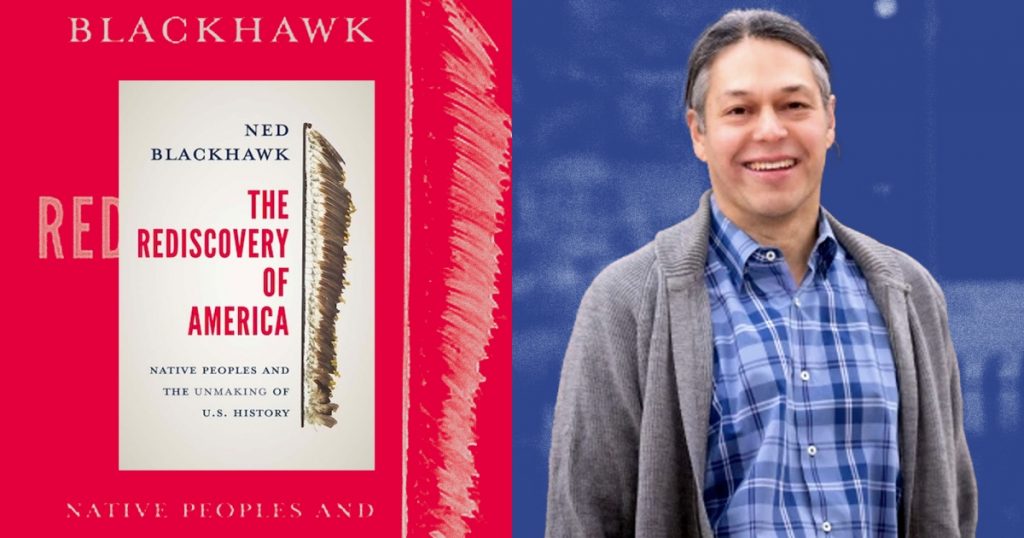

Ned Blackhawk Wants to Unmake the US Origin Story

Mother Jones; Dan Renzetti/Yale University Press

Fight disinformation: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter and follow the news that matters.In recent years, there has been greater awareness of the need to recast American history by including the stories of this nation’s original inhabitants. Museums have created lesson plans to impart to students a more comprehensive understanding of the erasure of Native peoples and more universities are offering courses on Native history. Ned Blackhawk’s The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History is a new, sizable contribution to this larger effort to denaturalize entrenched understandings of the nation’s story.

Deeply researched and engagingly written, the book is a monumental achievement. Spanning five hundred years, Blackhawk’s book recovers the histories of Native peoples who had as much a hand in creating this nation as their colonial counterparts. “A full telling of American history,” writes Blackhawk, the Howard R. Lamar Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University, “must account for the dynamics of struggle, survival, and resurgence that frame America’s Indigenous past.” Too often, works of history are written from a consolingly placid perspective; Blackhawk’s book teems with dramatic encounters between Native actors and white Americans and often gives a sense of how certain events came within an eyelash of happening differently or not at all. The volume asks the discipline of American history to question itself. And it feels especially urgent in a moment when many Indigenous people are newly imperiled, by anthropogenic climate catastrophes, pipelines, and polluting infrastructure.

In March, I asked Blackhawk about his new book, the paradigm of settler colonialism, and the potential of “Red Power.”

An idea that animates your book is that “encounter—rather than discovery—must structure America’s origins story.” Can you say more about this?

Discovery is not only a flawed category of historical analysis but also an unjust legal doctrine. The “Doctrine of Discovery” was used by the U.S. Supreme Court to legitimate federal taking of Indian lands and was just recently repudiated by Pope Francis for its centuries of harm. There are sections in my book about the centrality of Indian affairs to the emergence of American federalism after the Revolution that highlight the deliberations of early U.S. state leaders to organize the early Republic to effectively extend U.S. authority over interior Native lands and peoples.

More broadly, if we conceive of U.S. history as a process of European discovery, we fall into a series of problematic analyses that perpetuate long-standing limitations and often falsehoods. I believe that encounter invites alternative understandings of the American experience. It recognizes commensurate and multipolar sovereigns within an undetermined world, and more accurately reflects the early American historical experience when Europeans and colonial societies often remained small and less central social and political actors, especially in the earliest generations of settlements.

Your book is sweeping in scope, comprising 500 years of U.S. and Native American history. Can you briefly describe how you came to write this book?

I was quite shocked in graduate school to encounter simultaneously the great depth of U.S. historical inquiry and its nearly complete disavowal (at the time) of fundamental themes of Native American history: sovereignty, diseases, violence, resistance, dispossession, bilateral treaty-making, federal dominion and reservation self-governance.

I recently wrote about this disregard in a piece called “The Iron Cage of Erasure,” and have spent much of my career trying to intervene into assumptions about the making of America. There has been a recent generation of scholars who have uncovered a vast historical universe previously outside the scope of much of U.S. history, and my new book is indebted to this ongoing “rediscovery” of American history.

The theory of settler colonialism emphasizes, among other things, that violence is not a series of discrete events but rather a mode of state formation. The theory has been increasingly invoked of late in discussions of racism, sovereignty, and land access.

To what extent is settler colonialism a useful framework for thinking about American history, and what are some of the limitations?

It’s been quite exciting to see this paradigm come into formation and then explode over the past two decades. Many may not know that the theory of settler colonialism originated with Indigenous Studies who critiqued prior models of global colonialism that focused more on “post-colonial” than “settler colonial” societies.

The paradigm is process based. It recognizes the ongoing dialectic of colonialism as a feature of contemporary “settler” societies. While indebted to the settler colonial turn, many historians—myself included—worry about some of its totalizing features. As an idea that emphasizes “Indigenous elimination” as one of its central features, it often minimizes the agency, adaptation, and resurgence of Native American communities.

Can you briefly explain the doctrine of “plenary power”?

The Founding Fathers of the United States inhabited a multipolar world where Indigenous peoples and nations remained recognized powers. While often vilified—as in “merciless Indian savages” found in the Declaration of Independence—early U.S. leaders nonetheless understood Indian nations and sovereignty to be critical aspects of U.S. statecraft. The Senate’s first treaties are all with Indians, and Indian affairs informed the first bilateral treaties with European nations—starting with Jay’s Treaty of 1794.

This recognition of Indigenous authority became codified in the U.S. Constitution, most notably in the Commerce Clause’s granting of federal authority over “Indian tribes” and in recognition of “treaties made, or which shall be made… (as) the supreme Law of the Land.” I write at some length about the early contests around these powers, in particular Jefferson’s ironic reluctance to concede to the Executive and Senate’s exclusive, joint authority over the treaty power—after he became President, Jefferson used the same powers to get approval of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty.

This type of treaty-making often riled the Republic. Southerners—like Jefferson and later Andrew Jackson—bristled at the suggestion that Indians could potentially retain through treaties territorial jurisdiction and sovereignty within the U.S. legal system. Their followers did even more, especially in Jacksonian America when Indian Removal dominated national politics and prompted constitutional crises.

Plenary Power—as a doctrine—began largely in the 1850s after the formal portions of eastern Indian removal had concluded. It holds that Congress (including the House of Representatives) has authority to override U.S. treaty commitments with Native nations. Indians challenged these principles throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century, but a series of rulings established precedents that Congressional laws have “plenary power” and can thus override Senate treaty commitments—despite their standing as the “supreme Law of the Land.” So, Indian lands, resources, and even children grew threatened by new congressional laws, leaving Native nations with very limited protections. This doctrine has more recently been used to authorize other congressional actions and often seizures.

What is the ideology of “Red Power”? How did activists and organizers sow the seeds of the modern American Indian sovereignty movement?

Red Power refers to particular forms of Native American politics, advocacy, and activism that generally prioritize communal over individual rights. In its clearest articulations, it is a vision of Native American sovereignty that is dynamic, future-oriented, and historically determined in which bilateral relationships between the federal government and Native nations are not only upheld but also give way to greater forms of tribal self-governance and self-determination. It is an ideology that has animated Indian Country from over half a century and is identifiable not only in activist take-overs but also in arts, literature, music, film, and other forms of creative expression. I examine, for example, what became known as the “New Indian Art Movement,” that arose at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, established in 1962. It drew 130 students from nearly seventy tribes in its first semester. Trained by prominent Native artists who served on its faculty, many such as T.C. Cannon (Caddo/Kiowa) became national successes, “advancing an aesthetics of vibrancy and futurity… that both defined an era and reimagined the future.”