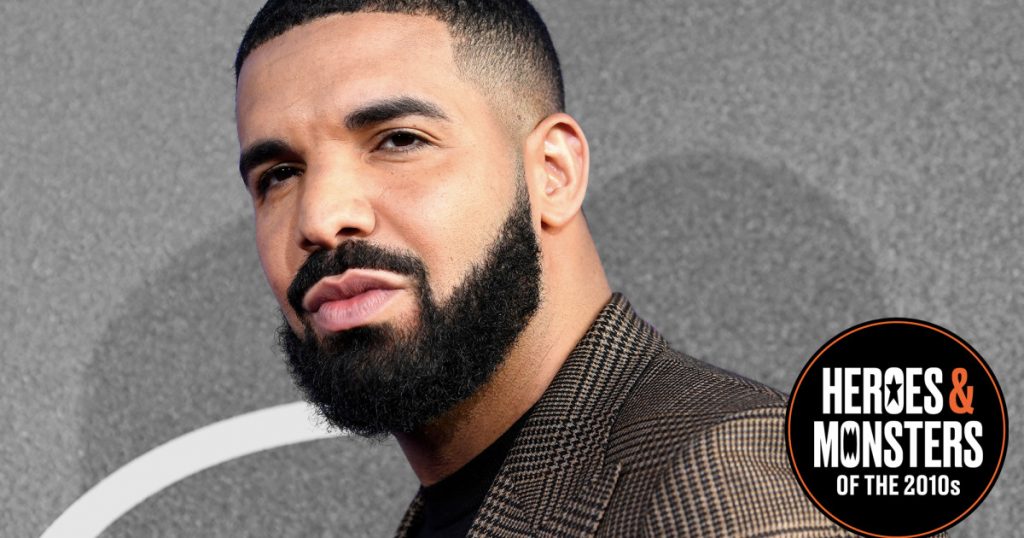

Monsters of the 2010s: Drake

Mother Jones illustration; Frazer Harrison/Getty

The staff of Mother Jones is rounding up the decade’s heroes and monsters. Find them all here.

Aubrey Graham is a person. “Drake” is a social phenomenon. He’s that dude who lives in sweatpants and Adidas slides, who ignores your texts for weeks then sends “Wyd” at 2 a.m. and you end up replying just ‘cuz the sex is decent. Drake is that controlling douche dating your friend (“Soon as you see the text, reply me”) who thinks he knows what’s best for her (“I know exactly who you could be”) even though he lives with his mom. Drake is always showing you his new SoundCloud demo, which is indiscernible from his last SoundCloud demo. You know you can do better than Drake, but his selfishness is so simple and familiar as to feel almost sweet.

The literal Drake was the most streamed artist of the decade, as well as its top digital sales artist. His hits were inescapable: “The Motto” (2011) cursed us with “YOLO” mentality. “Started from the Bottom” (2013) raised questions about Drake’s credibility, since he started as a middle-class Canadian actor on Degrassi. The video for “Hotline Bling” (2015) was seemingly made for viral GIFs (see above), and then there was “What’s My Name?” (2010) and “Work” and “Too Good” (both 2016), plus other collabs with Rihanna—who is, in fact, too good for him.

While not afraid to show emotion, Drake’s music glorifies ego-drunk, patronizing maleness. It’s not that he’s soft; it’s that he uses the softness as a weapon, a sort of predatory vulnerability. He’s been known to text and dine with teenage girls.

Everything about him carries the whiff of inauthenticity. He doesn’t write his lyrics—and shrugs off any suggestion that it matters. After rapper-songwriter Meek Mill called him out for using ghostwriters in 2015, the two traded diss tracks for years, the sparks from which reignited Drake’s feud with Pusha T, who said Drake’s fakeness was no secret: “The lyrics pennin’ equal to Trump’s winnin’/The bigger question is how the Russians did it.” Pusha later called attention to a photo of Drake in blackface and suggested the rapper had a secret love child, which Drake soon admitted.

Rap legends from André 3000 to Kendrick Lamar have chimed in to disparage ghostwriting, yet Drake, who was recently booed off stage, keeps topping the charts with songs like “In My Feelings.” If 12 people helped him write it, are the feelings really his? And if “Drake” is less a person than a team-designed product, do we only have ourselves to blame for buying it?

The figure of the manufactured pop star is as old as stardom itself, but the acquiescence to it, by wised-up people who know exactly what they’re buying, feels like something new. Drake is the rapper for our hyper-real age, singing in fluent post-irony to disillusioned zoomers. The villainy of Drake is that of the 2010s, of fake news, “social” media, Kardashians. He has been acting since he was 15. And the next time he hits us up, we’ll try not to text back, but in this desert of the real, we’ll take what we can get.