Kamala Harris Will Make Sure Racial Justice Is a Key Part of Joe Biden’s Climate Agenda

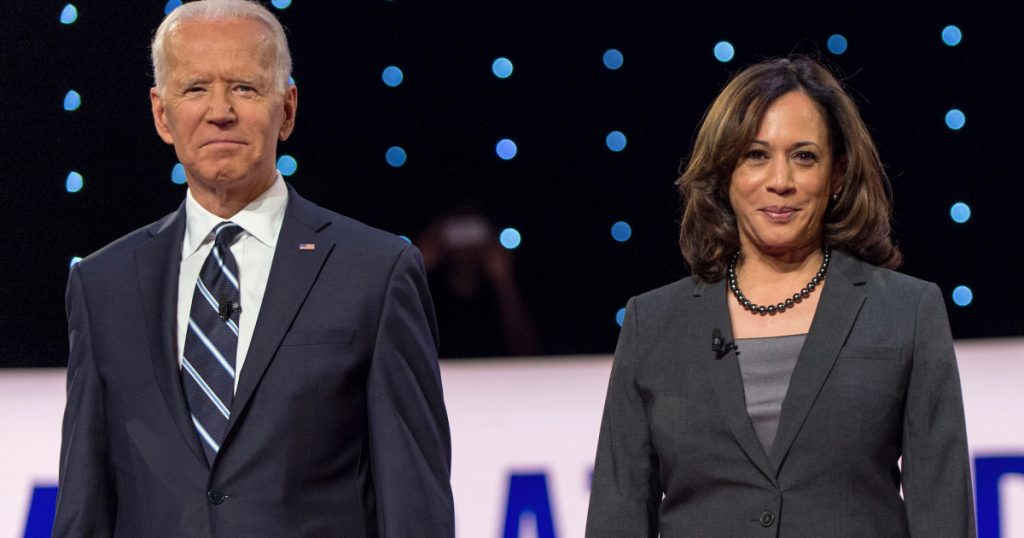

Brian Cahn/ZUMA

For indispensable reporting on the coronavirus crisis and more, subscribe to Mother Jones’ newsletters.Kamala Harris made history on Tuesday, becoming the first Black woman to be the vice presidential pick on a major party ticket. But she makes history in other ways, too. Her addition to Team Biden will focus a new spotlight on an issue Harris has championed in the Senate: addressing the racism of environmental pollution.

While climate change has grown in importance to Democratic voters in recent years, so has drawing the connection to racial injustices. We’re only now starting to reckon with a long history of white environmentalists and leaders chronically overlooking this crisis. And the coronavirus pandemic, which has disproportionately impacted Black and Brown Americans, is making the stakes clearer than ever—and makes addressing the pollution in these communities all the more urgent.

The past few years have been something of an evolution for the junior senator from California; when Harris entered the presidential race last year, she didn’t have as robust an environmental record as many of her opponents. Still, she campaigned to the left of Biden on climate change, calling for a nationwide ban on fracking when Biden has not gone so far, and firmly embracing the Green New Deal, a moonshot left plank of investment to bring down climate pollution (even calling for eliminating the filibuster to do so).

Perhaps most notably, last year Harris partnered with Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) to propose a draft bill, the Climate Equity Act, that would require an equity score to assess any environmental project’s impact on frontline communities, much in the same way the Congressional Budget Office scores the economic costs and impacts of bills. The proposal requires an extra level of scrutiny for White House executive actions on low-income communities and people of color, as well as feedback from those affected communities, and it creates a new Climate and Environmental Justice office to coordinate all the impact assessment efforts. Amid the veep speculation, Harris made headlines again this summer by officially introducing the act.

One of her last moves before the VP announcement was to partner with Sens. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Tammy Duckworth (D-Ill.) on a bill to reverse a 2001 Supreme Court decision that made it harder for Black Americans to sue under the Civil Rights Act for the disproportionate pollution in their communities. The Environmental Justice for All Act would also require the Environmental Protection Agency to consider the historical, cumulative pollution in a community before it could approve a permit for a new factory or highway.

“COVID-19 has laid bare the realities of systemic racial, health, economic, and environmental injustices that persist in our country,” Harris said in a statement in July. “The environment we live in cannot be disentangled from the rest of our lives.”

Another key plank of Harris’ environmental agenda has been an aggressive stance on the federal government’s role investigating fossil fuel companies for fostering climate change denial—a position that has highlighted her record as an attorney general in California. As my colleague Jamilah King explains, Harris’ “entire career could be defined by taking the ‘inside track’—trying to effect change within a broken system.” Last year, when I interviewed Harris in her final weeks on the presidential campaign trail, meeting at a frequently flooded site in Dubuque, Iowa, she was eager to talk about holding these actors responsible; she promised “that we’re going to put pressure on the big companies to do what is required and what is responsible.” She added, “let’s get them not only in the pocket book, but let’s make sure there are severe and serious penalties for their behaviors.”

It’s already clear that this positioning is having an impact: Joe Biden recently released his own platform focused on environmental justice, directing 40 percent of the federal government’s spending on clean energy to go to disadvantaged communities. In it, he also drew from policies that Harris herself has pushed, specifically including accountability for fossil fuel companies in Department of Justice investigations.

Many of these promises would fall flat if a president doesn’t appoint officials with a strong commitment to climate action to carry them out. Harris said as much in the interview last year, noting the importance of appointing climate leaders throughout the government’s ranks. Maybe she’ll be that voice.

“The president of the United States gets to appoint her cabinet,” she told me at the time. “And for me this issue of the climate crisis relates to every aspect of what we do.”