It Could Take Weeks to Find Out If Democrats Won the House

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

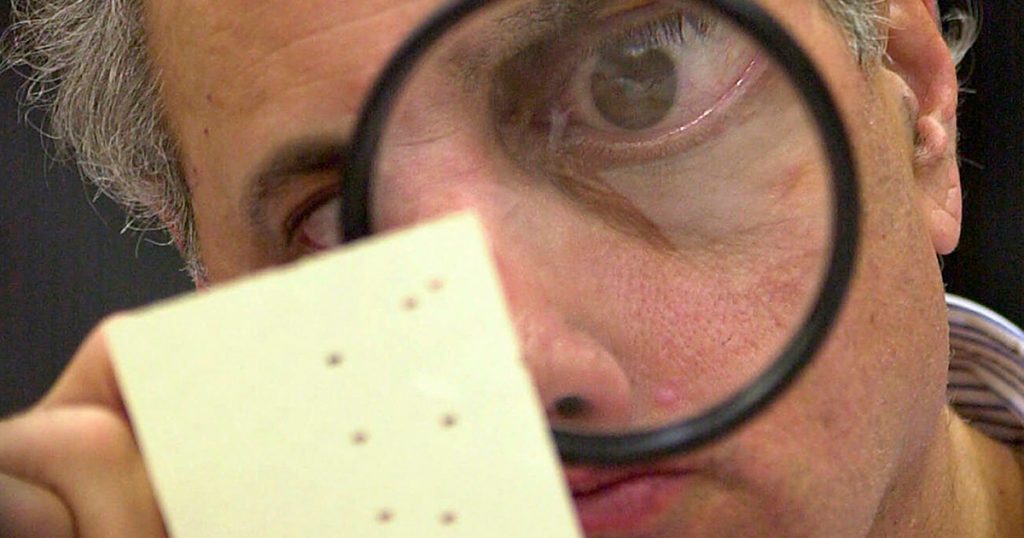

Remember this?

Alan Diaz / APIf you’ve been nervously counting down the days until the November 6 election, we’ve got some bad news for you: You might have to wait quite a bit longer before you know who will control the House. That’s because roughly a dozen key races are taking place in states where election officials often spend days or even weeks counting votes, making it difficult for media outlets to project the winners of close contests.

“The length of time it takes to come up with definitive results drives a lot of folks in the world of politics crazy.”California—home to at least seven competitive House races, according to the Cook Political Report—can take an especially long time to tally results, thanks in part to the state’s expansive vote-by-mail system. In 2014, the Associated Press couldn’t call the victories of Reps. Ami Bera and Jim Costa until more than two weeks after Election Day. Two years later, it took the AP 20 days to call California’s 49th congressional district for Rep. Darrell Issa. The state’s “top-two” primary took place on June 5 this year, but it wasn’t clear which candidates would move on to the general election in the 48th congressional district until June 24.

“The length of time it takes to come up with definitive results drives a lot of folks in the world of politics crazy,” says Darry Sragow, a longtime California political strategist and USC political science professor. “You’ve got candidates and campaign workers and party leaders and voters who are hanging on, waiting for the outcome, and in a close race you may not know for quite some time who the winner is.”

And since California’s swing districts are central to Democrats’ strategy to retake the House, the stress of delayed results could be felt well beyond the Golden State. Democrats need to gain 23 seats overall, and there’s a pretty good chance they won’t have reached that number by the time West Coast results start trickling in. If some of these crucial California races are close, the slow ballot-counting process could mean that the country will have an extended wait to find out which party will have a majority.

A similar scenario could play out in Washington state, where Democrats are targeting three GOP-held House seats. The state conducts its elections entirely by mail, and about half the vote generally doesn’t come in until after the night of the election, according to the AP. And Maine’s new ranked-choice voting system could mean a sluggish vote-counting process in the tossup 2nd congressional district. Mainers waited more than a week early this summer for the announcement that Janet Mills had won their state’s Democratic gubernatorial primary.

Any long delays could be problematic in a year when voters are so invested in the election—and when politicians, particularly President Donald Trump, have been spreading baseless fears about rigged elections and voter fraud.

All levels of government and Law Enforcement are watching carefully for VOTER FRAUD, including during EARLY VOTING. Cheat at your own peril. Violators will be subject to maximum penalties, both civil and criminal!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 21, 2018

The reason some California races are counted at a snail’s pace—aside from the sheer number of votes in the country’s most populous state—lies in the steps officials have taken to try to maximize voter participation.

Overall, says California Voter Foundation president Kim Alexander, “I think we do a much better job than other states on several fronts.” These include election security and verification—and making voting and registering to vote easier and more convenient.

“Most importantly,” Alexander says, “the biggest shift that’s happened in California in the last couple decades is that we have a growing number of voters who are voting by mail.”

In the 2016 general election, nearly 60 percent of Californians who voted did so by mail. In the 2018 primaries, that figure was nearly 70 percent.

“We’re trying to make sure we can count as many ballots as possible.”Voting by mail offers many advantages. It can be easier for residents of rural areas, older voters, and people with mobility issues. But California’s particular system of mail-in voting can also be extremely time-consuming. In many states, mail-in ballots won’t be counted unless they reach officials by Election Day. Californians’ ballots just have to be postmarked by Election Day and received no more than three days later. Similarly, Washington accepts ballots that are postmarked as late as Election Day. That’s easier for voters, but it means election officials don’t even receive all the ballots until several days after the election.

Once county officials in California finally receive all the ballots, they have to identify any that weren’t completed satisfactorily. For instance, election officials (with help from computers) compare the signature on each mail-in ballot envelope to the one on file from that voter’s registration documents. Most mismatches have innocent, non-fraudulent explanations—for example, someone’s signature may simply have evolved since they registered to vote years earlier, Alexander says. In past elections, officials simply invalidated these ballots, likely resulting in the disenfranchisement of some voters who had done nothing wrong. But in November’s elections, for the first time, officials will have to give voters a chance to fix the issue.

Under a new law, officials are required to attempt to inform voters about problems with their signatures so the voters can fix them. Haste is not mandatory, though. Officials have as long as 23 days after the election to notify voters, who would then have to verify their signatures—which they can do by mail, email, or fax, or in person—within 29 days of the election.

Then there’s conditional registration and provisional voting. Conditional registration is aimed at people who missed the voter registration deadline. In many states, these people are simply out of luck. Even in California, they aren’t allowed to vote by mail or at their local polling place. But they can register—and cast a ballot the same day—at designated locations, usually their county elections office. That ballot will be counted on the condition that officials can confirm the person is eligible to vote.

Californians can conditionally register right up to (and on) Election Day, so people who weren’t aware of registration deadlines, or couldn’t meet them, aren’t shut out of the voting process. But this also adds to the complexity and duration of vote-counting because officials then need to verify voters’ eligibility and check that they haven’t already voted elsewhere before the ballots can be tallied.

Provisional voting is intended for people who believe they’re registered even though their names aren’t on their polling places’ official voter lists. It is also useful for people who signed up to vote by mail but later want to vote in person—a helpful contingency for those who lose their mail-in ballots. Without this option, many people would miss their chances to vote. Nearly every state offers provisional ballots, but there’s a lot of variation in how voter-friendly these policies are. In the 2016 election, Californians cast more than 1.3 million provisional ballots—far more than in any other state, and 9 percent of all votes in California. Nationwide, provisional ballots accounted for less than 2 percent of all votes cast in 2016.

That means still more work for county election officials, who have to check that provisional voters are actually registered and haven’t already cast a ballot somewhere else—which the officials mostly can’t do until all the non-provisional ballots have been counted. Another hiccup arises when people vote provisionally outside of their assigned local polling places. Voters can cast their ballots at any polling place in their home county. But when people vote at polling places other than those they’re registered at, they often mistakenly vote on local down-ballot races they aren’t eligible to participate in—a city councilmember for a different neighborhood, for instance. When that happens, election officials have to individually remove those down-ballot votes, and that adds time to the process.

Election-watchers have voiced some concerns about provisional ballots, and voters have expressed skepticism that they are all counted. (Only a small percentage of provisional ballots in California get rejected, however—just 1.32 percent in 2016 and half a percent in 2014, according to MIT’s Elections Performance Index.)

At the same time, the United States Commission on Civil Rights has criticized the “indiscriminate use of provisional ballots” in California.

“This upsets me,” Alexander says, referring generally to the criticisms of policies designed to make voting easier. “People say, ‘Oh, California has so many people voting provisionally. That means that they don’t have their act together.’ Well, no—we’re giving people a failsafe that other states don’t give them, and we’re trying to make sure we can count as many ballots as possible.”

“I look at some of these other states that are like, ‘Oh, our election’s over; we’re done three days later,’” Alexander says. “I think, ‘OK. Who got disenfranchised in the process?’”