How John Lennon’s Murder Led to Preventing Mass Shootings

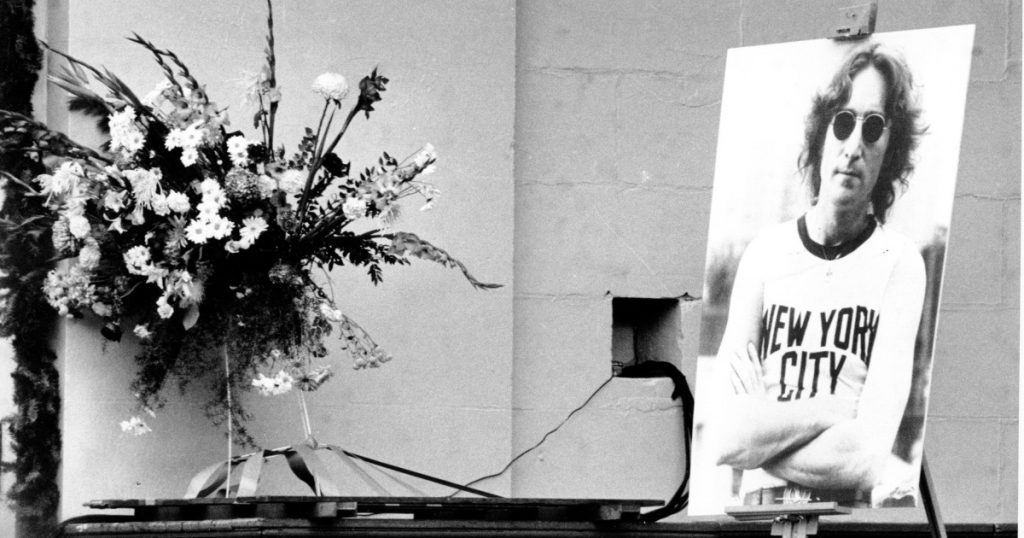

A week after the 1980 murder of John Lennon, a photo of him on display in front of his New York City home.Carlos Rene Perez/AP

Facts matter: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter. Support our nonprofit reporting. Subscribe to our print magazine.Editor’s note: This article is adapted from Mark Follman’s new book, Trigger Points: Inside the Mission to Stop Mass Shootings in America (HarperCollins). It first appeared as a guest column in David Corn’s newsletter, Our Land, a twice-weekly dispatch with stories and insights on politics and media. Subscribing costs just $5 a month—but you can sign up for a free 30-day trial of Our Land here.

The memorial gatherings spanned from New York and Chicago to London and Liverpool and many other cities around the world. Among the multitudes who defied winter weather and came together in public spaces throughout America, younger and older generations alike wept and embraced. Many clutched flowers or candles, or held up hand-drawn signs that read: “Imagine no more handguns,” “Give peace a chance,” or just “Why?” In New York’s Central Park on that Sunday, against a backdrop of leafless trees and a gray sky auguring snow, the tens of thousands who assembled stood still for an impossibly heavy ten minutes of silence, the vast hush of their mourning disrupted only by a helicopter circling overhead and the ambient murmur of the city carried on the wind.

It was mid-December 1980, and John Lennon was dead.

At the start of the following week, Dr. Shervert Frazier, one of the nation’s foremost psychiatric experts on violent behavior, arrived at Bridgewater State Hospital in Massachusetts. He knew the music icon’s devastating murder would resonate even more for forensic psychologist Robert Fein, a young protégé of his, and the rest of the growing team that Frazier had put in place at the maximum-security psychiatric institution.

Questions had been swirling in the media about Mark Chapman, the twenty-five-year-old assailant who for several days had waited around the Dakota building at the corner of 72nd Street and Central Park West. Late in the day on Monday, December 8, as Lennon had departed the posh residential building and paused to greet some fans out front, a grinning Chapman finally got an autograph from him on a copy of Lennon’s newly released album Double Fantasy. Then Chapman continued to linger.

It was almost 11 p.m. when Lennon and his wife and co-artist, Yoko Ono, returned from a recording session, stepping out of a limousine in front of the building. As the couple walked into the stately entryway, Chapman, wearing a black trench coat and fur cap, emerged from the shadows and reportedly called out, “Mr. Lennon.” He then took a “combat stance,” as a New York City chief of detectives described it, and fired four hollow-point bullets from a .38 caliber revolver into Lennon’s back. Lennon was rushed in a police car to Roosevelt Hospital, where doctors were unable to resuscitate him. Amid the shock and global outpouring of grief, Chapman was described by various news media and public officials as “an obsessed fan,” “deranged,” “a kook,” and “a wacko.”

Frazier, based at McLean Hospital near Boston, had just returned from a trip to Washington, DC, where he was serving on a committee for the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences. He asked Fein to gather the Bridgewater team, which included sixteen psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers. The timing for the news Frazier shared with them had become serendipitous: His IOM committee had been talking in recent months with the US Secret Service about developing behavioral science research to enhance capabilities for thwarting assassins.

One in every four presidents since the founding of the country had been the target of an assassin’s bullet, and the contemporary era was even more fraught with danger for top political figures. Following the slayings in the 1960s of President John F. Kennedy, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., and Senator Robert Kennedy, targets also had included Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter. There were two close calls involving President Ford, and a perpetrator who wanted to kill Nixon had gone on to gravely wound Alabama governor and presidential candidate George Wallace. Secret Service leaders were intent on improving the agency’s knowledge and tactics. To that end, Frazier told the assembled group that he had made an ambitious promise to a group of mental health experts and law enforcement officials: The Bridgewater team would produce the definitive study on mentally ill assassins.

Fein and the team were taken aback by the unexpected mission, but the conversation quickly focused on the fresh tragedy in New York City, including Chapman’s notably bizarre behavior after he pulled the trigger. “I’d go away if I were you,” he had said to a woman who approached him just moments after the gunfire to ask what happened. Chapman was not interested in escaping. He had dropped his weapon and had hung around nearby on the sidewalk, where he pulled out a copy of The Catcher in the Rye and thumbed through it briefly until police swooped in. He apparently wanted to convey that he embodied Holden Caulfield, the landmark novel’s embittered young protagonist. Chapman had grown up devoutly religious during a period of his youth in Georgia and had deemed Lennon to be among the “phonies” of the world, resentment he may have rationalized in part over Lennon’s famous assertion in a 1966 interview that Christianity would decline and the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.”

Chapman’s performance at the crime scene, however, was more than a jarring example of an assassin’s pathological identification with a fictional figure. Unbeknownst to Chapman, he had just created a new version of a “cultural script”—a kind of narrative template for future killers to mimic.

Assassins and mass murderers sometimes looked to notorious predecessors for inspiration, picking up on their appearances and actions in what would come to be called copycat or contagion behavior. Behavioral science experts were already familiar with a related historical phenomenon known as the “Werther effect,” which referred to a contagion of suicides in eighteenth-century Europe that followed the literary success of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. Some of the novel’s readers dressed up like its romantically despondent protagonist and shot themselves, sometimes even with a copy of the book in hand. Chapman would gain certain disaffected admirers, a harbinger of the emulation behavior that would animate rampage shooters in the decades ahead and draw the attention of threat assessment experts.

The Bridgewater team knew that the potentially dangerous vitriol focused on celebrities and politicians went beyond the shocking attacks known to the public. The facility housed some men who had threatened to kill the US president or other high-profile figures, a danger now made vivid by Lennon’s death. What drove these would-be assassins? “Let’s start with what more we can learn here,” Frazier said to Fein and his colleagues, urging that they examine such behavior by also talking directly with the Secret Service. And they had to complete this research project quickly—in time for an elite gathering of mental health and law enforcement leaders that Frazier was helping to organize that would take place three months later in Washington.

Over the coming weeks, Fein and several colleagues pored through Bridgewater case files, reviewed their interactions with violent offenders, and met with Secret Service agents from Boston and Washington. By early March, they had finished their report.

At that point, Frazier, Fein, and their research colleague Sara Eddy traveled to the nation’s capital to meet behind closed doors with Secret Service leaders and a handful of luminaries from research institutions around the country. A primary goal of the confidential gathering was to establish active working ties between special agents and top experts on behavioral science, mental health, and the law.

But were federal agents really going to start working hand in hand with psychologists to thwart murder plots? The role of law enforcement was to investigate crimes, not to prevent them. Even with the unique protective mission of the Secret Service, which relied on arresting suspects under what was known as the federal “threat statute,” such a development was unlikely.

The bland title of the new report from the Bridgewater team hardly exuded lofty ambition for collaboration: “Problems in Assessing and Managing Dangerous Behavior.” Yet the opening section contained the contours of a new discipline. It described how experts could work together to “identify, assess, and manage” the relatively tiny number of people who might consider or take action to kill top public figures.

The clinicians observed that no scientifically valid method existed for determining “dangerousness” in people and that trying to predict over the long term whether a person would commit an act of violence was likely futile. But in individual cases it might be possible to anticipate such behavior in a useful way. “Rather than think about dangerous people,” they wrote, “we prefer to think about dangerous situations—situations involving a specific subject, a victim, and an act under specific circumstances.”

This was a striking leap forward from the traditional practice of violence risk assessment, which involved time-consuming clinical observation and analysis of an individual. Instead, the team of clinicians was suggesting how the Secret Service could tap psychological expertise in a much more immediate and pragmatic way.

They spelled out protocols for quickly evaluating subjects of concern. This included getting a handle on their mental health and their relationships with others, assessing any serious grievances they might have, and determining whether they appeared capable of carrying out a violent attack. The team further suggested setting up a national network of mental health practitioners experienced with violent offenders, proposing that these experts should be available as needed “around the clock” to consult with agents on evaluations and threat management plans.

The fact that the opaque and close-knit Secret Service still operated in old-school ways posed a challenge. The agency was created within the Treasury Department in 1865 to combat rampant counterfeiting—after being authorized by President Abraham Lincoln, in an uncanny historical twist, on the very day he would be assassinated. Its mission eventually came to include presidential protection after the assassinations of James A. Garfield in 1881 and William McKinley in 1901. Now, the better part of a century later, a rethinking of the agency’s ingrained culture and methods, catalyzed by the March 1981 gathering of experts in Washington, would prove consequential for the evolution of behavioral threat assessment. Secret Service leaders were enthusiastic about pursuing the innovative research and collaboration, though securing the necessary buy-in and funding amid the federal bureaucracy promised to be daunting.

But then, just three weeks later, the mission took on a sharp new urgency after a fresh horror unfolded in the nation’s capital. On the afternoon of March 30, 1981, as President Ronald Reagan departed from a speech to labor leaders at the Washington Hilton Hotel, a twenty-five-year-old man in a trench coat standing among the press corps in the light drizzle opened fire with a revolver. One bullet fired by John Hinckley Jr. ricocheted into Reagan’s torso, puncturing the president’s left lung and stopping an inch shy of his heart. Other shots gravely wounded Reagan’s press secretary, James Brady, leaving him paralyzed, and seriously injured a police officer and a Secret Service agent.

Hinckley had fixated for years on the teen actor Jodie Foster, watching her repeatedly in the 1976 film Taxi Driver, writing her letters, and stalking her at Yale University. He apparently came to believe he could win Foster’s heart if he became famous. Like the paranoid and alienated young protagonist in Taxi Driver, he would attempt a high-profile political assassination.

Several threads twisted together in Hinckley’s version of the cultural script. The screenplay for Taxi Driver had drawn inspiration from the diary of Arthur Bremer, the young man who had sought notoriety by targeting Nixon and later shooting Governor Wallace. Among the possessions federal agents found in Hinckley’s DC hotel room was a copy of Bremer’s diary.

The agents also found another volume: The Catcher in the Rye. Hinckley had paid close attention to Chapman. On audio tapes Hinckley recorded shortly after John Lennon’s recent murder, he had talked of how Lennon and Foster were in his mind “binded” together: “John and Jodie, and now one of ’em’s dead.” The recordings also contained Hinckley strumming a rendition of Lennon’s love song “Oh Yoko!” on a guitar, swapping in “Oh Jodie!” as he sang.

The shootings of Lennon and Reagan spurred groundbreaking research into an array of different killers. Fein would later collaborate with Secret Service agents to go inside prisons and psychiatric institutions around the country. Over several years, they devoted many hours to interviewing and building rapport with notorious offenders, including Chapman, Hinckley, and nearly two dozen others. The unique insights these experts gained into “pre-attack thinking” and behaviors became key to a growing method that years later would start to help thwart dozens of mass shootings.

Postscript: It is important to add here that the threat assessment experts who pursued this groundbreaking research went on to discover that mental illness was not the cause of most mass shootings, as was initially thought. The claim that mental illness “pulls the trigger”—often pushed after massacres by those advocating for no legal restrictions on guns—is wrong. I document this through extensive case research and the further history of behavioral threat assessment chronicled in Trigger Points.