Here’s Why the Carolinas Are So Much More Vulnerable to a Hurricane Like Dorian Right Now

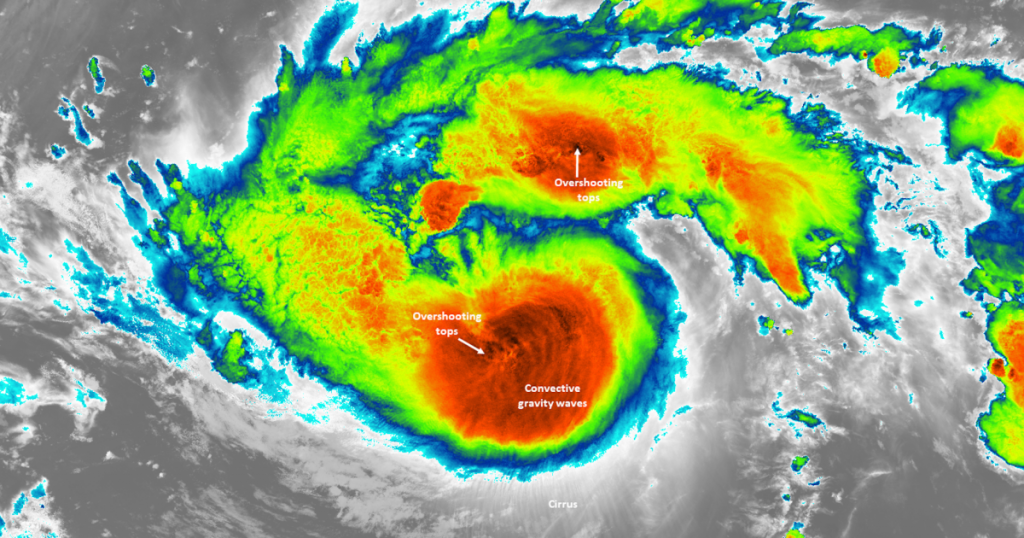

NASA

Puerto Rico has escaped the worst of Hurricane Dorian. And it looks like Florida might, too: On Saturday morning, the storm again shifted paths, and it appears likely to skirt Florida’s eastern coast instead of making a direct hit. That doesn’t mean the danger is over for Florida, and it does put the rest of the southeastern coast, especially Georgia and the Carolinas, in harm’s way sometime next week. South Carolina has already declared a state of emergency. Worse still is if the Category 4 storm makes landfall in vulnerable areas still recovering from last year’s Hurricane Florence.

The stakes have grown much higher when a hurricane threatens to hit the coast. There are a lot of reasons for this. As I explained two years ago, “Some are psychological, others are practical, and many are self-inflicted.” Climate change is part of the problem, with warmer temperatures fueling deadlier, wetter storms. Rising sea levels increase the chances of coastal flooding. But it’s also the blind spots that North Carolina politicians have developed on climate change. While seas are rising, these lawmakers have encouraged building in low-lying areas, and in some cases discouraged state law from reflecting scientific realities.

The Carolinas are flanked by low-lying narrow barrier islands that have seen housing and tourist development during the past few decades “in places where it probably should not have been,” according to the Associated Press. Much of that development has been subsidized by a federal flood insurance program that shelled out $1.5 billion to cover flood claims in two dozen coastal counties even before Hurricane Florence struck. Last year, when Florence made landfall as a Category 1 hurricane, it dealt the region $24 billion in damages and 53 deaths. The floodwaters breached hog lagoons and coal ash pits and threatened Superfund sites.

Unwise development isn’t the only problem. As in Florida, North Carolina politicians have also allowed climate change denial to dictate their decision-making.

In 2010, a panel of scientists advising the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission, which guides the state’s coastal development, issued a report projecting 39 inches of sea-level rise by the end of the century. The report triggered political backlash from developers and the Republican-controlled legislature, which preferred that the commission rely only on historical data. The state ended up passing a law requiring a broader range of projections to dilute findings that sea level rise would accelerate. Newer research has found that the sea level is rising even faster along the southeastern coast than global averages. Instead of considering the best science out there, the governor-appointed commission ultimately limited the science panel’s projections to 30 years into the future.

North Carolina’s Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper, elected in 2017, has begun to loosen these restrictions on how development plans incorporate the latest science. Last year, a month after Florence struck, Cooper issued an executive order to create an interagency climate change council. In late September, the Coastal Resources Commission will look at updating the 30-year limit placed on the science advisory panel as it prepares a five-year update to its 2015 report, according to The News and Observer.

Hurricane Dorian may end up reinforcing the hard lessons from Hurricane Florence in North Carolina—even if those lessons won’t reach President Donald Trump.

.@realDonaldTrump, who canceled a planned trip to Poland this weekend in order to monitor #HurricaneDorian, has just arrived at his golf course in Virginia, the White House says.

— Jeff Mason (@jeffmason1) August 31, 2019