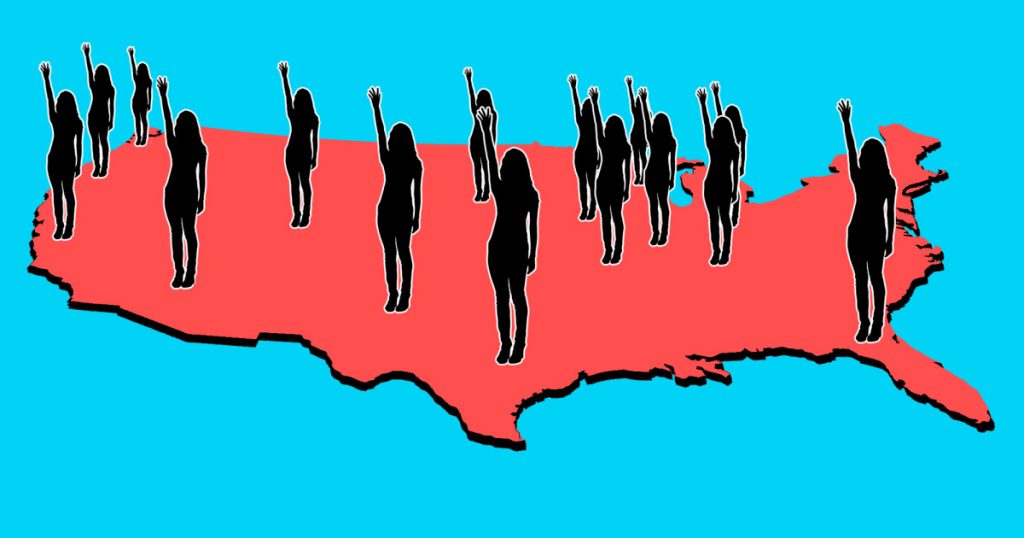

From Oregon to Maine, Statehouses Are Having Their Own #MeToo Reckonings

Mother Jones Illustration

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

As the #MeToo movement has gained steam following the damning sexual misconduct revelations against producer Harvey Weinstein in October, more and more women around the country have spoken out about a pervasive and unchecked culture of sexual harassment in American politics. So far, six lawmakers have been forced to leave Congress in response to related allegations, and statehouses around the country have been roiled by accusations from staffers, lobbyists, and even fellow elected officials. Stateline found that at least 18 state lawmakers who faced allegations of sexual misconduct have either resigned, announced they will resign, or been punished to some extent.

Here’s a rundown of the headline-making controversies at state capitols from Tallahassee to Seattle—and how legislatures have responded:

It started with a Facebook post. For years, Republican state Rep. Michelle Ugenti-Rita wrote on October 19, she had dealt with “unwanted sexual advances and lewd and suggestive comments regarding my body and appearance from male colleagues.” Weeks later, Ugenti-Rita told a local Arizona TV station that Don Shooter, chair of the Arizona House Appropriations Committee, had harassed her since she got to the statehouse.

Shooter denied Ugenti-Rita’s allegations, but the allegations kept rolling in. At least nine women, including the publisher of the Arizona Republic, have come forward with accusations of sexual misconduct.

Response: On November 10, House Speaker J.D. Mesnard suspended Shooter as appropriations chair. Two House attorneys are leading an investigation into the sexual-harassment allegations levied against Shooter, an inquiry Shooter says he requested.

On October 17, a letter signed by more than 140 women called out the California Legislature for its own “pervasive” culture of sexual misconduct following the Harvey Weinstein scandal. “Each of us has endured, or witnessed or worked with women who experienced some form of dehumanizing behavior by men with power in our workplaces,” wrote political consultants, current and former legislators, and Democratic and Republican party officials.

The Sacramento Bee then reported that three women came forward with allegations of sexual misconduct, and the Senate launched an investigation into State Sen. Tony Mendoza, a Democrat, who was accused of inappropriate behavior. In one instance, a young woman who worked as a fellow in Mendoza’s office said the senator invited her to his house after a party to review her résumé. A former legislative aide claimed Mendoza repeatedly texted her and invited her to attend after-hours engagements with him. He was stripped of his leadership positions but has since refused to step away from the state Legislature.

Raul Bocanegra, a Democratic assemblyman, stepped down from office after six women came forward with allegations of unwanted sexual advances or unwelcome communication. In 2009, the California Assembly Rules Committee had disciplined him for groping another female staffer.

On December 8, Democratic Assemblyman Matt Dababneh announced his intention to resign from the Legislature at the end of the month. Four days earlier, lobbyist Pamela Lopez filed a complaint with the California Assembly and accused Dababneh, who has been in office since 2013, of following her into a bathroom in Las Vegas, telling her to touch his genitals, and masturbating in front of her—allegations Dababneh denied.

Response: The California Senate Rules Committee announced that it would relinquish control of sexual-harassment investigations and leave the work to an outside law firm. Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León, who is challenging US Sen. Dianne Feinstein in the 2018 election, moved out of a house he stayed in with Mendoza, and a spokesperson told the Sacramento Bee that de León did not know about the allegations until they were reported on this year.

On November 28, a former legislative aide filed a complaint against Republican state Sen. Randy Baumgardner, claiming that he had slapped and grabbed her buttocks several times over the course of three months in 2016. In a separate incident, Megan Creeden, a former intern, told the local radio station KUNC that Baumgardner made inappropriate advances toward her and pressured her to drink with him in his office. (Baumgardner refused to comment in a statement to KUNC.)

Meanwhile, state Rep. Steve Lebsock faced complaints of sexual misconduct from fellow Democratic Rep. Faith Winter and former lobbyist Holly Tarry. Lebsock, who is currently running for office to become state treasurer, has resisted calls for his resignation and claimed some of the allegations are “significantly exaggerated” and others “completely false.” On December 14, Lebsock released the results of a polygraph test that he says shows he’s innocent.

Response: Colorado House Speaker Crisanta Duran and Senate President Kevin Grantham called for legislative changes to improve the ways sexual-harassment complaints are handled. On December 15, lawmakers voted to hire a consultant tasked with examining the Legislature’s approach to addressing sexual harassment and to bring aboard a human resources employee. Both lawmakers called for a review of existing misconduct prevention policies. Grantham told the Denver Post he wanted an alternative online option for reporting complaints, and Duran requested that a third-party investigate misconduct allegations, a departure from the current system where the House speaker and Senate president handle complaints.

In October, after a state senator was discovered to have had an affair with a lobbyist, the Florida state Senate made changes to how sexual-harassment complaints are reported, directing all claims to the Senate president’s office. Then, another scandal broke: At least six women who worked in the state capitol told Politico Florida that Republican state Sen. Jack Latvala, then the state Senate’s budget chairman, had sexually harassed them.

The accusers included lobbyists and staffers from both parties, and many of them chose to stay anonymous for fear of retribution. After State Senate President Joe Negron ordered an ethics investigation, one accuser came forward: Rachel Perrin Rogers, a state Senate aide who accused Latvala of groping her and of making inappropriate comments. Latvala, who is running for governor, called Politico‘s story “totally fabricated” and vowed to clear his name.

Response: On November 3, following Politico‘s report, state Senate President Joe Negron ordered an investigation into Latvala’s actions, calling the allegations “atrocious and horrendous.” On December 20, Latavala told Negron in a letter that he planned to resign from his seat in January, following two Senate reports that found “probable cause” that Latvala engaged in “inappropriate and unwanted physical contact” with Rogers and propositioned a lobbyist for sex in exchange for support on a vote, a claim that could bring criminal charges. (He has not said whether he would continue his campaign for governor.) On November 7, several female lawmakers, led by state Sen. Lauren Book, proposed bolstering Florida’s ethics laws to make it illegal for elected officials to use sexual coercion as a bargaining chip for official acts. Currently, the state law makes it a crime for an official to ask for and get gifts but doesn’t mention sexual harassment.

On December 13, Gov. Rick Scott, who called on Latvala to resign if the allegations are proven true, imposed an executive order that forced state agencies to adopt sexual-harassment policies that required training for all employees and outlined how to report and investigate misconduct complaints. The agencies would also designate someone other than an employee’s immediate supervisor to receive sexual-harassment complaints and prevent contact between the accuser and the accused for the duration of the investigation. The order doesn’t extend to the state Legislature, however.

Another state, another letter. On October 24, more than 160 men and women signed an open letter demanding changes to a toxic culture in Springfield. The letter laid out how women, candidates, staffers, and lobbyists encountered sexual harassment while working in Illinois’ political scene, from a committee chair saying a female staffer had a “nice ass” to a candidate who made advances on a fundraising consultant and refused to pay her. “Every industry has its own version of the casting couch. Illinois politics is no exception,” the letter stated. “Ask any woman who has lobbied the halls of the Capitol, staffed Council Chambers, or slogged through brutal hours on the campaign trail. Misogyny is alive and well in this industry.”

On November 1, state Sen. Ira Silverstein, a Democrat from Chicago, left his position as head of the Senate Democratic majority caucus a day after activist Denise Rotheimer told lawmakers he’d made inappropriate comments about how she looked and had barraged her with Facebook messages and calls when she worked with him on legislation. Silverstein denied the allegations, adding that he apologized if his actions made her feel uncomfortable.

Response: Following the allegations against Silverstein, Illinois Senate President John Cullerton announced on November 1 that lawmakers would have to take a seminar on sexual harassment when they returned to Springfield. Unlike other states wrestling with the fallout from sexual-misconduct allegations, Illinois lawmakers quickly passed a bill that empowered the state legislative inspector general to investigate 27 unanswered ethics complaints and another that mandated sexual-harassment training, as well as a resolution that created a sexual-harassment task force. The Illinois General Assembly had been without a legislative inspector general for more than three years.

In late September, Kirsten Anderson, a former GOP communications director in the Iowa Senate, settled a sexual-harassment lawsuit against the State of Iowa in which she argued she’d been fired hours after she filed a complaint in May 2013 describing a toxic work environment. Republican State Senate Majority Leader Bill Dix didn’t dispute Anderson’s allegations but maintained that Anderson had been relieved of duties for poor work performance.

In the lawsuit, Anderson accused former Republican Senate policy analyst Jim Friedrich of saying the “c-word” in reference to women and making racially charged jokes. Friedrich resigned on September 13.

Response: After the settlement, Republican leaders planned to hire a director of human resources but eventually changed course. Instead, Dix tapped Mary Kramer, a former Republican Senate leader and human resources director, to advise the Iowa Senate on improving the workplace environment. And the Senate released an internal review of its workplace culture between December 2012 and July 2017, showing that the Senate had ineffective policies to address workplace harassment; at least one Republican caucus staffer had made “sexually suggestive comments to others,” the Des Moines Register reported.

In Topeka, the #MeToo movement began with legislative staffers, advocates, and interns. Abbie Hodgson, who worked as chief of staff for state Rep. Tom Burroughs, a former state House minority leader, told the Kansas City Star on October 25 that a male lawmaker had asked her to have sex during a Democratic fundraiser. She described how female interns were called by several male Democratic lawmakers to serve as designated drivers. “I expressed my shock, concern and outrage to Rep. Burroughs and asked if he was going to do anything about it. He said no,” Hodgson told the Star. Burroughs disputed the account and said he took immediate action. Following Hodgson’s revelations, interns came forward with their own accounts of inappropriate remarks, with one former intern telling the Star that the Legislature could be a “very sexually objectifying environment.”

Response: Lawmakers asked the Women’s Foundation, a women’s advocacy group that helped reform Missouri’s sexual-harassment policies in 2015, to review on the state Legislature’s 23-year-old policy, which some lawmakers acknowledged they didn’t know existed. Meanwhile, Democratic lawmakers in the state House will receive sexual-harassment training before they return to session in January.

Kentucky’s Courier Journal reported in November that the state’s House speaker, Jeff Hoover, reached a sexual-harassment settlement with a legislative staffer over allegations from 2016. Three other Republican representatives—Reps. Jim DeCesare, Brian Linder, and Michael Meredith—and Hoover’s chief of staff signed the settlement, prompting calls from Gov. Matt Bevin for lawmakers to “censure and remove” those involved in the arrangement.

Bevin, who called the scandal a “cancer in our legislative body,” proposed an amendment at the Republican State Central Committee meeting on December 2 that would have asked for the resignation of anyone who entered settlements on sexual-harassment claims.

Response: Hoover stepped down from his position as speaker of the Kentucky House but has refused to leave his post. He has admitted to sending messages to the woman but says they were consensual. The other members left committee leadership positions but didn’t address their roles in the settlement.

Republican leadership took a different course after another state lawmaker was accused of sexual misconduct. On December 11, Kentucky’s Republican Party chair Mac Brown and four other House leaders called on Rep. Dan Johnson to resign after it was revealed that Johnson had been accused of sexually abusing a 17-year-old girl from his church in 2013. Johnson refused to resign, calling the allegations “unfounded.” On December 13, Johnson drove to a bridge outside Mount Washington, Kentucky, parked his car, and shot himself with a handgun. His wife says she wants to run for his seat.

A dozen women told the Boston Globe in late October about sexual misconduct that had persisted at the State Capitol over the last two decades. “Aides, lobbyists, activists, and legislators told of situations where they were propositioned by men, including lawmakers, who could make or break their careers; where those men pressed up against them, touched their legs, massaged their shoulders, tried to kiss them, grabbed their behinds, chased them around offices, or demanded sex,” wrote the Globe‘s Yvonne Abraham. The accusers and accused were unnamed.

Days after the allegations came to light, state House Speaker Robert DeLeo, who said he was “deeply disturbed” by the allegations, and state Senate President Stanley Rosenberg acknowledged that they had received complaints of sexual harassment before. “It’s not only a State House issue. You’re hearing stories in other states and nationally as well,” DeLeo told reporters.

Response: The story prompted DeLeo to order the House’s counsel to review the chamber’s policies and procedures, evaluate training materials given to legislators, and determine how the chamber investigates harassment complaints, all in the hopes of ensuring “a workplace free of sexual harassment and retaliation.” The counsel will send back recommendations in March 2018.

Meanwhile, members of the Women’s Caucus Sexual Assault Working Group requested that the state House move forward with a five-point plan to address sexual-harassment concerns. That plan included mandatory training for state employees and a survey on the scale of harassment in the Massachusetts Legislature.

In late November, Republican state Rep. Tony Cornish and Democrat state Sen. Dan Schoen each resigned from the Minnesota Legislature after they both were accused of harassing women. Lobbyist Sarah Walker claimed that Cornish, who had been in the statehouse for eight terms, had pressured her for sex and pushed her against a wall in his office. Cornish had also exchanged text messages with a fellow representative, Erin Maye Quade, with inappropriate comments. (Cornish denied most of the allegations.)

Cornish and Walker reached a settlement in which Cornish would resign, publicly apologize, and pay for any attorney fees. A MinnPost investigation found that Schoen, a freshman state senator, had sexually harassed several women and sent a picture of his genitals to one woman on Snapchat. Schoen told MinnPost that the allegations were “either completely false or have been taken far out of context.”

Response: The resignations embroiled the Minnesota Legislature. On December 11, two lawmakers proposed changes in the state House to allow staffers, lobbyists, and any members of the public to confidentially lodge sexual harassment and discrimination complaints with the House Ethics Committee. The Republican-led state Legislature will likely take up the issue when the session begins in February.

“During my five years as a state representative, I have personally experienced harassment in the Roundhouse,” state Rep. Kelly Fajardo wrote in a letter to House and Senate leaders in November. “I have also witnessed instances of harassment where colleagues and lobbyists have been subject to repeated profane comments and innuendo. I heard stories of sickening quid pro quo propositions where legislators offered political support in exchange for sexual favors.”

Fajardo, a Republican, urged the state Legislature to fix its two-page sexual-harassment policy and recalled her own experience with harassment. She added that the Legislature should enlist the help of an independent ethics commission to investigate harassment complaints, expand harassment policy to cover lobbyists and others, and make stronger retaliation protections for those filing a complaint. Women who have worked at the New Mexico statehouse echoed Fajardo’s remarks.

Vanessa Alarid, who worked as a lobbyist in New Mexico, recounted one such moment to the New York Times. Alarid said that while meeting with former state Rep. Thomas Garcia to discuss an upcoming bill, he told her, “You can have my vote if you have sex with me” and kissed her. She rebuffed the lawmaker, and the bill eventually fell by one vote. Garcia denied that he asked for sex in return for his vote.

About a week after Fajardo’s letter, State Sen. Michael Padilla, seen as a rising star in the Democratic Party, lost his position as Senate Majority Whip and dropped out of a race for lieutenant governor after concerns surfaced over decade-old harassment complaints from a past job. He denied the allegations, saying in November: “This is not who I am, and this is not a pattern.”

Response: State lawmakers began rewriting its sexual-harassment policy, which as it stands would leave investigations into lawmakers’ misconduct to a panel of legislators, rather than an independent entity. The House speaker or Senate president would examine complaints made against legislators, and the House and Senate at large can decide to punish a lawmaker who engages in inappropriate behavior. Senate majority leader Peter Wirth said he is suggesting new preventative training on harassment before the Legislature convenes in January.

In late October, a state memo surfaced detailing how state Sen. Cliff Hite made sexual advances on a female state employee over the course of two months. It included allegations that he repeatedly asked the employee for sex, despite constant refusals. He resigned abruptly on October 16 without explanation. Days later, Hite conceded that he engaged in inappropriate conversations with a state employee.

The list of Ohio politicians mired in sexual-harassment allegations grew after that. Michael Premo, who was chief of staff for Ohio’s Senate Democrats, resigned on November 13 following what Ohio Senate Minority Leader Kenny Yuko called “concerns of inappropriate conduct toward staff.” Days later, Republican state Rep. Wes Goodman resigned after Ohio’s House Speaker found out Goodman engaged in inappropriate, consensual behavior with another man in his state office, the Columbus Dispatch reported.

Response: In an open letter, dozens of Democratic female lawmakers and legislative staffers called on the state Legislature to make decisions beyond imposing sexual-harassment training to change the culture there. That includes increasing the number of female lawmakers in leadership roles and continuing “to convey that we have zero tolerance for harassment in our legislature.” State Sen. Charleta Tavares said in the letter that she was working on a bill to address sexual-harassment issues.

In mid-October, state Sen. Sara Gelser took to Twitter to accuse a fellow lawmaker of inappropriate behavior. She initially didn’t name the lawmaker, but days later, Republican state Sen. Jeff Kruse lost his committee assignments.

On November 15, Gelser filed a formal complaint against Kruse, alleging that the Republican senator touched her breasts and inappropriately touched her during a committee hearing. She called on the Legislature to expel Kruse as senator. In the complaint, Gelser noted that at least 15 other women had raised concerns about Kruse’s behavior. Kruse has denied that he engaged in inappropriate behavior and groping.

Response: Following the allegations, 130 women, from lobbyists to lawmakers, signed a letter modeled after the one sent by women who worked in California’s Legislature, calling on Oregon’s Legislature to create a culture “where it is expected that people (both men and women) will speak up when it is happening in front of them, and ensure that it is safe to report it when it happens in private.” On October 27, state House Speaker Tina Kotek announced the Legislature would hire a consultant to review the governing body’s harassment policies.

Emboldened by the #MeToo messages circulating on social media, several Rhode Island lawmakers came forward with their own stories of sexual harassment. Perhaps the most shocking came from State Rep. Teresa Tanzi, who, on October 16, told the Providence Journal: “I have been told sexual favors would allow my bills to go further.” She added that the remark came from “someone who had a higher-ranking position.” The story prompted Rhode Island’s attorney general to launch an inquiry into Tanzi’s allegation.

Reponse: House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello announced that House members and staffers would receive sexual-harassment training in January. Senate members and staffers will join them. Mattiello asked Tanzi to chair a commission to review the the issue of workplace harassment and assault. Meanwhile, on October 26, former state lawmaker Joseph DeLorenzo quit the Democratic Party—and his top party position—after he received backlash for remarks he made about Tanzi’s account during a radio appearance. “My first reaction is it goes right into the narrative that the far left wants portrayed out there,” DeLorenzo told WADK’s John DePetro. “Everything is sexual harassment today. If a woman walks into my office and I say to her, ‘Boy, you look nice in that dress’—sexual harassment. A woman walks in that I know—and we do this all the time, John—put your arm around her, give her a kiss on the cheek—sexual harassment, sexual harassment.”

In Austin, a whisper network documented alleged instances of sexual-harassment women faced from legislative staffers, lawmakers, and campaign workers. On November 13, the Texas Tribune reported that a pervasive culture of sexual misbehavior simmered in the Legislature without formal action, with the House operating under an outdated harassment policy.

On December 6, the Daily Beast reported that Democratic state Sen. Borris Miles propositioned a legislative intern for sex outside a bar in May 2013 and tried to forcibly kiss women on separate occasions when he was a state representative. Miles’ spokesperson told the Daily Beast the allegations “unfounded and implausible.” Meanwhile, several women accused state Sen. Carlos Uresti of inappropriate behavior, both as a senator and earlier in his career as a state representative. In a statement to the Daily Beast, Uresti, a Democrat, called the allegations “unfounded” and “erroneous.”

Response: On December 1, members of the Texas House revised its chamber’s sexual-harassment policy to clarify what constitutes misbehavior and require all House members and staffers to participate in sexual-harassment training by January. Meanwhile, the state Senate began examining whether to change its 22-year-old policy governing sexual-misconduct cases. The policy doesn’t delve into how complaints of misconduct should be handled, the Dallas Morning News reported. Despite a call from Annie’s List for Uresti’s and Miles’ resignations, no state senator has called on either fellow lawmaker to step aside, the Texas Observer reported.

While no lawmaker has been publicly outed for sexual misconduct, lawmakers, lobbyists and other women who have navigated the halls of Vermont’s statehouse have described varying levels of sexual harassment and sexism they’ve faced from lawmakers. When she was a newly elected legislator, Mitzi Johnson, now Vermont’s House speaker, told the alt-weekly Seven Days that she once refused unwanted advances from a male lawmaker. Another legislator, state Rep. Sarah Copeland-Hanzas, told Seven Days that she had to report a male lawmaker’s misbehavior to the Democratic majority leader after the lawmaker rested his hand on her behind in the cafeteria line. It never happened again, she says.

In early December, Vermont Public Radio reported that someone had filed a previously undisclosed formal complaint to the Senate Sexual Harassment Panel against a sitting senator in April, during the last legislative session. The senator’s identity and the nature of the complaint are confidential; state Sen. Becca Balint, who chairs the panel, told VPR that the panel met with the two sides and the matter was “settled without formal disciplinary action.”

Response: The disclosure, along with the stories sweeping the nation, prompted both state House and Senate leaders to consider changes to how the legislature addresses sexual harassment. The Legislature recently updated its harassment policy after former state Sen. Norm McAllister was charged with sexually assaulting a legislative intern in 2015. He was later acquitted of that charge but found guilty of arranging with a friend a trade of sex with his accuser for money. McAllister was ousted from the state Senate in January 2016.

On October 31, nine current and former legislative staffers and lobbyists described an atmosphere in the Washington statehouse in which inappropriate behavior and unwanted advances were the norm. On November 1, several women accused former state Rep. Brendan Williams of unwelcome sexual advances and harassment, including a lobbyist who claimed that Williams had inappropriately touched her during a work dinner. Williams, who left the Legislature in 2011, told the Associated Press that he stood by his record on “supporting the dignity and rights of women” and threatened a lawsuit “both against the person making the allegations and any media outlet publishing them.”

Then, a top Democrat in the state House revealed following inquiries that former state Rep. Jim Jacks abruptly resigned in 2011 after he was accused of sexual misconduct toward a legislative staffer at a bar. A former legislative staffer told the Northwest News Network that she had been harassed by Jacks two years before his resignation.

Shortly after, more than 170 women signed a letter to Democratic and Republican leaders, calling for a change in the culture at the Washington statehouse, “from one which silently supports and perpetuates harassment to one which supports and preserves safety.”

Response: On November 14, the state Senate facilities and operations committee imposed a yearly sexual-harassment training for senators and staffers. Washington’s House of Representatives also required training for lawmakers.

Top image credit: drbimages/Getty; StockImages_AT/Getty