For Queer Parents Like Us, the Demise of Roe Feels All Too Familiar

Facts matter: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter. Support our nonprofit reporting. Subscribe to our print magazine.This week, as my youngest child prepares to graduate from high school under the looming shadow of the end of Roe v. Wade, I find myself remembering a moment soon after the birth of his older brother. Our overly sleepy newborn needed a blood test. Stitched and battered, I shuffled into the office of a hospital administrator who called me only Mom and rattled off the perfunctory questions—Name? Social? Medical record number?—except, for the first time, the questions weren’t about me but about my son. It was the first time, too, for a particular hitch of unrecognition: “Mother’s name?” she asked without looking up. “Father’s name?”

“Mothers,” I corrected her. “He has two mothers.”

The birth of a first child transforms a couple into a family; the arrival of our son was also a moment in the birth of a movement, one that in a relatively short time has transformed the world from a closed place to a more open one. This is what we want for our children—to see the world grow with them. But with the death of Roe, I wonder if the opening that has defined our parenthood will snap closed again. I wonder what else we have that will get taken away.

Back in that hospital administrator’s office, my own mother was sitting beside me. She and my father had come to the Bay Area for the birth of their first grandchild, who was like the trump card we’d played on all of their disappointment that I was gay. They could meet the news of my engagement with Do you really want to do this? They could stagger through the wedding like zombies. But the first grandchild? They couldn’t say meh to a baby. And they didn’t—they were smitten. A baby didn’t magically fix my relationship with my parents, but it did fix something. Later that night, after the visit to the hospital, my mother gushed: “You’re so brave!”

I didn’t feel brave. I felt like I was just living the life I meant to live. I’d spent my 20s chanting We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it! Boomer lesbians had babies together before we did. This wasn’t new. And yet, in the history of the world being written and erased under our feet: so fragile, so new.

Gay and lesbian families with children are certainly new to the law, and our family’s history records the evolution of that legal status in strata whose clay is still damp to the touch. My wife and I first married in 1999, in a big, beautiful ceremony in the Berkeley Hills with a rabbi, a klezmer trio and a DJ. We smashed a glass and ate passion fruit mousse cake covered with gardenias. The one thing our wedding did not have: recognition from the state.

Our children were born into this legally liminal relationship, and extraordinary legal remedies were required to ensure that they would be recognized as fully and completely ours. When our oldest son was born at the turn of the millennium, the state did not recognize my spouse as his legal parent on his birth certificate. There was a workaround that allowed her to adopt him, but it was just that—a workaround.

At that time, the only biological mothers entering into adoption agreements were women who had chosen to give up their babies. When I sat down in the little downtown Oakland house that had been converted into our lawyer’s office, that is the paperwork she handed me: the forms a mother would sign when she was legally relinquishing her child. Flooded with all the juicy hormones of weepiness and attachment, I read the relevant paragraph twice and then a third time. There was no asterisk, saying, No, not really. I just met this boy and I am never giving him up. Was I actually going to sign this thing? I was terrified.

Our lawyer leveled her gaze at me across the wood-paneled room that looked like my father’s den: “Sign it.” That first adoption required multiple social worker visits to our home—a home in which two committed partners had planned and conceived the child—and culminated in an audience with a judge.

Our second son was born three years later, in 2004. The State of California by then allowed same-sex parents to adopt their partner’s biological children through what’s known as a second-parent adoption, a slightly less onerous process that was designed for step-parents, and still included lawyers and legal fees, social workers and judges, but at least it omitted the breathtaking declaration of surrender.

It wasn’t until 2008 that my spouse and I were able to go down to the county courthouse to hear the words guaranteed to raise goosebumps for any queer couple of that era: “with the power invested in me by the State of California.” Our school-aged children were there with their pals, each little fist clutching a single Gerbera daisy. We got to the courthouse just in time. That November’s election gave us our first Black president, but also a ballot measure called Proposition 8—a state constitutional amendment that took away the right of couples like us to marry in our home state.

The California ban remained in place almost five years before a 2013 US Supreme Court decision rendered it unconstitutional. But true security for our marriage and for our family as a legal entity didn’t come until 2015, when the Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges made marriage equality the law of the land.

People who aren’t gay—and even some who are—sometimes don’t believe me when I remind them that we’ve only had the right to marry for a handful of years. The decision was recent enough that, when our younger son needed to provide proof of residency to play on his regional Little League All Stars team, the certifying umpires refused to accept a water bill in my spouse’s name and an electrical bill in mine and a mortgage in both as proof of residence. “Sorry,” the coach emailed early on a Saturday morning. “They need proof that you’re a family.” How many heterosexual families, I wondered, had to submit a marriage certificate to send their sons out to the infield?

In the seven years since Obergefell, though, we’ve seen how relieved fellow parents, neighbors and strangers have been to give up the assumption of heterosexuality. “What does your partner do?” they ask now, instead of your husband. Most people we encounter seem happy to find themselves in this new world that acknowledges humanity’s various realities. They want to be in on what in another era might have been a secret.

And in these past seven years, teens in our sons’ circle have been proudly identifying as queer and non-binary in numbers and ways that were unthinkable when I was in high school. This is progress. This is what we want for our children.

It’s so tempting to believe, as Martin Luther King Jr. preached, that the arc of the moral universe bends towards justice. But with the recent legal assaults on gay and trans children in Florida, Alabama, and elsewhere; the banning (and perhaps burning) of books; and the likely reversal of a cornerstone Supreme Court decision that has shaped women’s access to health care and opportunity for most of my time on this planet, it seems that, with enough brute force, the arc can also be bent in the opposite direction.

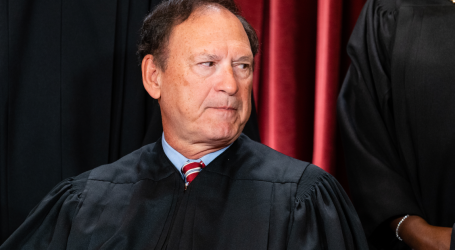

It’s a strange moment to be a queer family whose young men have come of age only to see some of their own freedoms revoked. Reproductive freedom, after all, shapes the lives of men and women alike. It seems possible, too, that my children, who professed boredom, ate cupcakes and sailed paper boats at the Oakland Rose Garden after they watched their parents get legally married, may also watch that right get taken away. Samuel Alito, the justice who authored that draft Roe-abolishing opinion, was likewise among the court’s Obergefell dissenters. (Clarence Thomas and the late Antonin Scalia penned their own opposing opinions.)

I worry for my sons and their peers; I worry that these young people who have grown up facing the specter of environmental devastation will see their own rights stripped from them one by one and just give up. Too long a sacrifice, Yeats wrote, can make a stone of the heart. I’ve seen signs of this nihilism, which can seem the only antidote to anxiety and despair. It’s not what I want for my children.

This week, as my son walks across the stage and flings his cap into the air in that ceremony that marks an end of childhood yet is paradoxically called a commencement, I will do my best to remember that what seems like an endpoint is only ever a point along the way. What matters is that you don’t give up, I want to tell my sons and their friends, remembering those defiant marches of my 20s, voices raised, fists waving, remembering the aisles of Target now stocked in June with rainbow flags. No matter what, you keep going.