For Disabled Workers, Discrimination Is Common—If You Even Get to Apply

Mother Jones; Getty

Fight disinformation: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter and follow the news that matters.After becoming blind in his late 20s, designer and artist Marco Salsiccia had to learn to navigate the world through assistive technology—like a screen reader, software that speaks digital text and image descriptions aloud. Leveraging that experience, Salsiccia began work as an accessibility specialist, eventually working part-time at a well-known tech startup based in San Francisco (a key site of disability rights activism since the late ’60s).

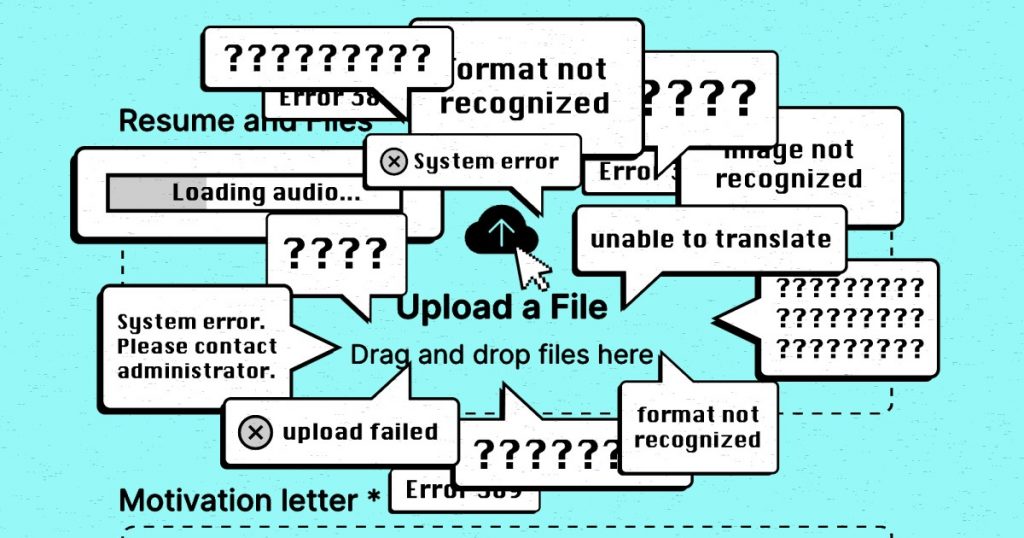

Over five years later, a full-time role opened up. Salsiccia set out to apply. His screen reader gave him the job description—which he’d also helped write. Next, he was prompted to upload a resume. But that part of the application, on an outside platform, hadn’t been tested with screen readers. His fell silent.

“I had to get my wife who is sighted to come over and do that for me,” Salsiccia says. “It pulls all autonomy away.”

Before landing her current job, Amy Albin, a blind 25-year-old in New Jersey, worried that emails asking for accommodations would just end up in a “black hole.”

“While I’m waiting to get accommodated, the next people are already being interviewed and hired,” she says.

Albin now works for assistive tech provider Vispero, where she is able to help make workplaces more accessible.

Salsiccia’s experience isn’t unusual for Blind job seekers, but it’s a problem that could easily be avoided with pre-launch testing. Many employers choose not to—which leads to fears like Albin’s about asking.

Most Blind people, and those with low vision, face accessibility barriers to employment, including on job boards, tests and screening, and on-the-job training, as highlighted in a 2022 report by the American Foundation for the Blind. Nearly 80 percent of people without disabilities are employed—for Blind job-seekers or those with low vision, it’s barely two in five.

“We’ve had a collective experience that taught us [that] disclosing your blindness too early can result in simply not being allowed to move further,” says Daniel Frye, an attorney and the National Federation of the Blind’s director of employment and professional development.

October is National Disability Employment Awareness Month, when many US corporations’ social media posts celebrate their disabled workers, sometimes even quoting one on how great the company is. But as stories like Salsiccia’s reveal, even at the biggest and best-resourced companies, accessibility is often an afterthought at best.

Tech failures are the tip of the iceberg. In practice, employers also deter disabled applicants by loading job listings with questionable or avoidable demands: being able to lift up to 50 pounds at an accountancy job; mandatory, full-time returns to office—a turn-off for, among others, millions of Americans with regular flare-ups of autoimmune disorders; rushed timed interviews for people with conditions like traumatic brain injury, who may need more time to process questions.

Accommodating those conditions can make good business sense. Any company with a federal government contract worth $10,000 or more is expected to set a goal of having at least 7 percent of employees identify as having a disability, per the Rehabilitation Act. Accommodations like flexible hours for medical appointments attract a wide range of staff. Others, like limiting scents that may trigger severe health reactions, come at little or no cost. Making workplaces and tech accessible from the start is cheaper than paying for retrofits, says Teresa Goddard, a consultant with the Job Accommodation Network, which provides resources on accommodation to both employers and workers. But the biggest cost to firms could be the applicants they lose. “Job-seekers who experience barriers,” Goddard says, “might simply choose to pursue other opportunities.”

Companies don’t have to provide feedback about why they didn’t hire someone, which can make discrimination impractical or impossible to prove. Even if they do, employers can claim that an accommodation causes “undue hardship.” And, Frye says, the “emotional energy involved with filing an appeal” with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is considerable. The EEOC does sue employers for discrimination, as it did last week in the case of a staffing company that allegedly wouldn’t place Blind workers in customer service positions—provided people to come forward about their experiences.

That leads to a valid fear on the part of Blind people, and those with other disabilities: not much keeps prospective employers from passing them over if they find it complicated, expensive, or just undesirable to offer accommodations like assistive tech.

The Job Accommodation Network suggests some key steps for employers, like management training on accessibility devices, best practices, and the benefits of accommodating telework, along with dedicated funding and staff to manage accommodations. And in July, the EEOC released guidance on companies’ legal obligations to accommodate Blind people and others with low vision from the hiring process to employment.

In his new role at Deque Systems, a web accessibility company, Salsiccia gets to push clients to think seriously about developing the most accessible apps.

“I really love talking with designers,” Salsiccia says, “getting them to think beyond the visual and more about how everyone uses their technology.” He has similar conversations with quality assurance engineers about testing with tools like screen readers. Having those discussions “further up in the pipeline,” Salsiccia says, “is the best way to go about this.”