“Document, Reassure, Keep Calm”: A Behind the Scenes Look at Training Citizens to Respond to ICE

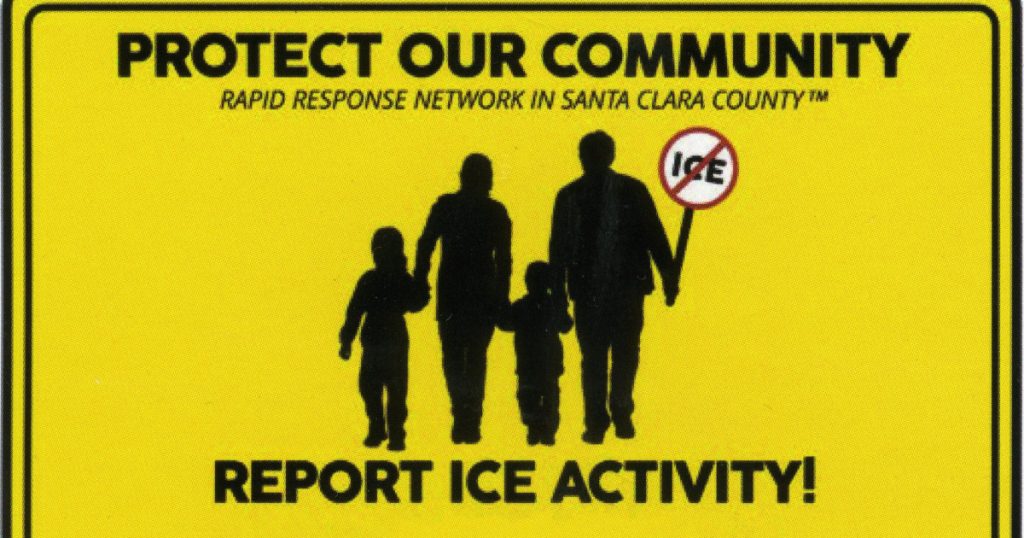

Courtesy Sacred Heart Community Service

Standing in front of a group in a small conference room at a community center in Cupertino, California, Megan Swift told the story of when she was too late. “I went in and they’d been grabbed,” she tells the crowd of 25 or so earlier this week.

About four months ago, she got an alert that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents were nearby and that they were detaining people. Most of the time she has gotten these alerts in the past, they were false alarms. But that day in early March, the threat, calling her to a specific address in San Jose, was real—”It was a house full of life that was just empty,” she explains. When she showed up, the door was wide open and the TV was still on, suggesting she’d missed the raid by just a few crucial moments. “That day made me recommit.”

“It was a house full of life that was just empty.”Swift is a trainer with the Rapid Response Network in Santa Clara County, a group of about 800 volunteers in the Northern California area that is tasked with responding to and documenting local ICE activity. The network runs a 24-hour hotline that anyone can use to report ICE sightings in their neighborhood. The hotline dispatcher will then contact volunteers in the area to observe and take notes about or video of the interactions between ICE and undocumented immigrants. They want to ensure that ICE agents aren’t violating immigrants’ rights and also to get enough information to connect detainees with immigration lawyers after they’ve been arrested. When the incident is over, once the ICE agents leave the scene—or if responders arrive to find it was a false alarm—volunteers canvass the neighborhood, pass out cards with the hotline information, and remind undocumented families of their rights if ICE agents are to show up.

Rapid response networks like this one have popped up around the country in the past few years as a response to President Donald Trump’s harsh immigration policies. In California alone, there are roughly 25 known and active networks. Others have ramped up their efforts in Wyoming, Colorado, and elsewhere.

Since the Rapid Response Network’s inception in May 2017, it has seen a steady increase in volunteers, says Carol Stephenson, the group’s community defense advocate who organizes these trainings and manages the responders. Recently, Stephenson and Swift have noticed a change in motivation among their volunteers, who are largely concerned citizens or documented immigrants not at risk for deportation. When previously the volunteers felt simply angry or frustrated, they say now they’re energized and ready to take direct action to protect their community.

“We’ve written letters. We’ve voted accordingly. We’ve grumbled to our neighbors and co-workers,” Swift says. “This [training as a rapid responder] is the next step.”

“It’s not so much that there is more ICE enforcement, it’s that people are on high alert.”That, of course, makes sense given the current environment; just last week, Trump tweeted that ICE would “begin the process of removing” millions of undocumented immigrants, particularly families, from the country. While later Trump announced he was delaying the action, and it’s unlikely that raids of this magnitude will actually happen, his statements have worked to instill even greater fear within the undocumented community.

As a result, just in the past week, the Rapid Response Network saw registrations for its trainings double, to over 40 from the usual 20 people. Though attendance Tuesday night in Cupertino isn’t as full as expected, Stephenson and Swift say they have had an especially busy month with over six trainings in June, up from the usual two trainings per month. Recently, they’ve also seen increased attention in a few specific cities with high immigrant populations, like Mountain View, and in sanctuary cities, like San Jose. In both, they try to canvass a few times a week to ensure people there know who to call next time ICE is nearby.

And last weekend specifically, Swift and her peers noticed more calls from people who were scared and wanted to make sure the hotline was working and the network was still active.

On average, they send responders out about five to six times a month. They say there’s been an increase in calls in the past few months, but mostly, they’ve been false alarms. “It’s not so much that there is more ICE enforcement, it’s that people are on high alert,” Swift says.

The group, in turn, works to dispel rumors. At the training Tuesday, Stephenson and Swift emphasize that when volunteers are canvassing a neighborhood, they shouldn’t say that they have received reports of ICE agents nearby. “You’re there to document, reassure, and keep calm,” Stephenson tells the group. Instead, the women suggest volunteers ask people in the area if they’ve seen any recent ICE activity.

They warn to look for American-made SUVs with “impossibly blacked-out windows” and white cargo vans.Trainers get pretty specific in the sessions, down to what ICE agents might be wearing and what cars they might be driving. They warn to look for American-made SUVs with “impossibly blacked-out windows” and white cargo vans. Often, agents will be dressed in regular street clothes, but they’ll have weapons and badges on their belts which can make them harder to spot from afar. Stephenson also tells me that she’s seen a change in their tactics: In the past year, agents have been less likely to knock on someone’s door. Instead, they’ll wait until someone gets in their car and pull them over. People will always stop for law enforcement, she says, and they have to show identification if they’re driving.

Perhaps the most important takeaway of the training this week was that as responders, volunteers can’t interfere with any federal agents or try to stop any arrests from happening. “This is not about us. It’s about protecting the community,” Stephenson says to the group. They tell responders not to interact with the detainees in any way—not to record them or give out any legal advice in the moment.

Stephenson and Swift center the training on the worst case scenario: ICE agents are at someone’s door, responders have shown up, and not only are the ICE agents trying to detain someone, but they’ve started coming after the responders—either telling them to stop recording or threatening arrest. While they’ve never had this situation actually unfold, they say it helps to outline the role that every responder should play in case it does.

Stephenson and Swift reassure the volunteers that recording and observing is within their rights. “We are not at risk. We do not want any of our actions to be taken out on someone who may be detained,” says Stephenson.

In an ideal scenario, the network wants five individuals at each incident—each with a specific job depending on experience and level of comfort. The first and most important role, according to the trainers, is the camera person tasked with recording the ICE agents. The second works as the notetaker who is expected to record details of the interaction, like license plates, badge numbers, hate speech or profiling from the officers, and any type of physical force or weapons used. Swift and Stephenson caution the group against adding their own judgement to their notes since they are often used by attorneys as evidence. “We just want the details verbatim without emotion in it,” Stephenson says. After any ICE activity, responders send in their photos, videos, and notes to the Rapid Response Network dispatchers, who will send it directly to the detainee’s attorney and delete them.

As those two people are recording, a third person works as the ICE liaison; in the unlikely event that agents start to question or harass the camera person or other responders, this person would distract the agents away from the person recording, perhaps by asking a lot of questions or playing the role of a concerned and confused resident. Finally, they also suggest a second camera person there to record the first camera person, as a backup in this worst-case scenario, and then one last person to walk around and talk to community members who are near the scene.

Some of the 25 at the training on Tuesday are there after being personally affected by deportations. Jocelyn Rodriguez is a US citizen, but both her parents have been deported. When her dad was arrested at work, he didn’t know his rights, she says. A big reason why she signed up to be a responder was so she could learn how to protect undocumented people like her parents.

“This information needs to be more accessible,” Rodriguez tells me. “We’re not doing our job as citizens to help people feel less afraid.”