Congress Is Set to Make the Rich Richer—Again

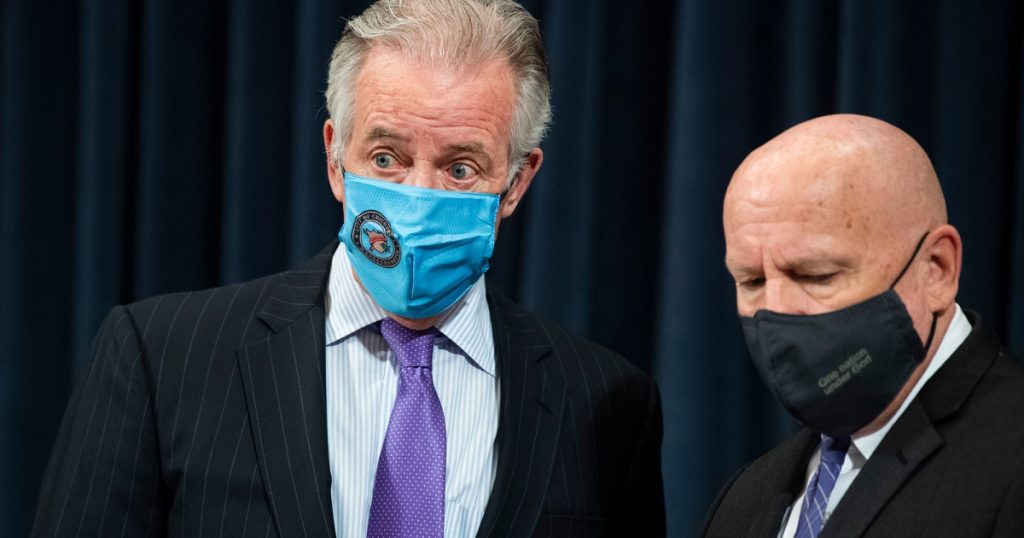

Reps. Richard Neal (left) and Kevin Brady.Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call/Zuma

Fight disinformation. Get a daily recap of the facts that matter. Sign up for the free Mother Jones newsletter.Powerful members of Congress, with the backing of the retirement services industry, are set to advance bipartisan legislation that will expand on the accomplishments of past “retirement reform” bills—namely, enriching wealthy individuals and Wall Street money managers at taxpayer expense.

Over the past 25 years, as I described in a recent Mother Jones article, federal lawmakers, notably Sens. Rob Portman (R-OH) and Ben Cardin (D-MD), have championed a series of bills that relaxed longstanding limits on government-subsidized retirement plans, resulting in an explosion of the savings gap between rich and poor Americans.

Federal tax breaks for private plans (as opposed to Social Security) now cost the US government almost $380 billion per year—a staggering sum—and those subsidies skew heavily in favor of the wealthiest, including tens of thousands of Americans who have millions of dollars saved and require no further help.

Last September, the House Ways and Means Committee introduced language intended for the Build Back Better bill (see page 665) that would have prevented taxpayers with $10 million or more in retirement savings from making additional contributions to a tax-subsidized plan. But even that modest proposal didn’t survive the sausage-making process.

The latest retirement package comes from another bipartisan duo, Reps. Richard Neal (D-MA) and Kevin Brady (R-TX), the House Ways and Means chairman and ranking member, respectively. The pair has revived their Securing a Strong Retirement Act of 2021 (SECURE 2.0), which follows on a similarly named bill (the SECURE act) that Brady and Neal pushed through Congress in 2019.

In a 2022 working paper titled “The Great American Retirement Fraud,” Michael Doran, a finance expert at the University of Virginia school of law, commented on the earlier legislation: “Although it included a few sensible provisions (along with many unimaginative ones), the thrust of SECURE was to increase retirement-savings subsidies and decrease retirement-plan regulation, just like the Portman-Cardin bills from the 1990s and the early 2000s.”

SECURE 2.0, which Brady and Neal intend to hitch to some piece of fast-moving legislation in the coming days, “offers more of the same,” Doran wrote: It “would further relax the required-minimum-distributions rule and would further increase contribution limits, both to the unambiguous benefit of affluent individuals. Among its few sound provisions, SECURE 2.0 would require automatic enrollment for section 401(k) plans.”

Indeed, a 2012 study quoted in the bill’s official summary suggests that automatically enrolling workers (other than those who opt out) in company 401(k) and 403(b) plans would markedly increase participation among younger, lower-paid workers, and could even wipe out the racial participation gap, which tends to be substantial. But giving low-income workers access to a retirement plan doesn’t mean they’ll have any money to save.

I recently spoke with Deana Bradley, a 38-year-old who for 16 years has worked as a cook at a nursing home in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Bradley has two grown children and two in middle school. She gets $15 an hour for weekday shifts—$21 on weekends. Her company used to offer a 401(k) match, but no longer does, and she’s not participating. She cannot, in any case, afford to put aside more than about $80 per month. “I’m paycheck to paycheck for sure,” Bradley told me.

Lots of Americans live paycheck to paycheck. In 2019, according to data from the Federal Reserve’s most recent Survey of Consumer Finances, families from the bottom 25 percent of America’s wealth distribution who participated in a tax-advantaged retirement plan had median savings of only $4,700. But participating families from the wealthiest 10 percent of the population had a median of $700,000 socked away.

SECURE 2.0 offers tax credits to small businesses to help set up new retirement plans, and to encourage bosses to give workers a matching contribution. But the latter credit is paltry, maxing out at $1,000 per employee per year, depending on how much the worker contributes. That’s the same maximum amount that low-income workers can claim under the federal Savers Credit, which another SECURE 2.0 provision promises to promote more effectively. One expert I contacted called this provision “a bad joke.”

The problem with the Saver’s Credit isn’t marketing, he said, but the fact that it is aimed at workers who don’t make enough to contribute to a retirement plan in the first place. (To claim the full $1,000, a single worker with taxable income not exceeding $20,500 must contribute $2,000 annually—about 10 percent of their earnings, or more.)

SECURE 2.0 also increases “catch-up” contribution limits and expands the age at which retirees must start cashing out their plans—both of which, as I explained in the earlier piece, are benefits that low-paid workers can’t realistically utilize. But these provisions will allow affluent Americans, at public expense, to shift more assets from their taxable investment accounts into tax-exempt retirement accounts.

These various retirement packages are catnip for both parties. (“There’s no question, it would move across the floor with more than 400 votes and a lot of momentum,” Brady told Roll Call.) That’s partly because they benefit key voting constituencies. But it is also because, by means of budgetary trickery, the bills can be made to appear as though they pay for themselves. “The ‘pay-fors’ are gimmicks, which generate revenue in the budget window, but lose money eventually,” explains attorney Steven Rosenthal, a senior fellow at the Brookings-Urban Tax Policy Center who follows retirement policy closely. “Congress should be embarrassed.”