Coal Communities Fear Exclusion From Environmental Justice Initative

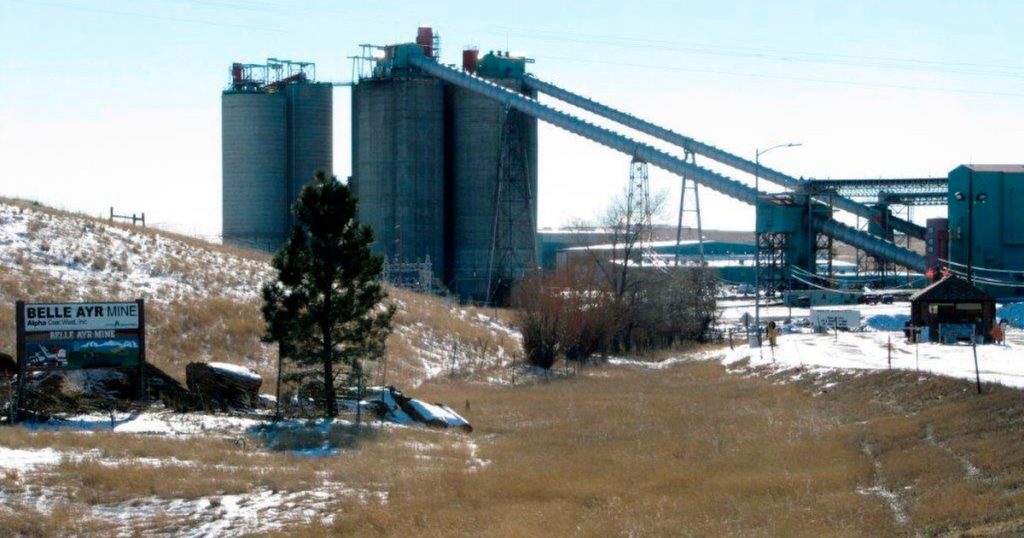

Belle Ayr Mine near Gillette, Wyoming Mead Gruver/AP

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Officials from declining coal communities in Wyoming worry that the Biden administration’s environmental justice agenda is hurting their ability to compete for billions of dollars in federal clean energy and infrastructure grants, including funding that’s intended to help communities that stand to lose the most from the nation’s transition away from fossil fuels.

According to reporting from Wyofile, historic coal towns like Gillette, Wyoming, are failing to obtain federal clean energy grants despite a faltering economy and what they call strong applications. Local officials and economists from the University of Wyoming say it’s because Campbell County, in which Gillette is located, doesn’t qualify as a “disadvantaged community” under President Joe Biden’s Justice40 initiative.

Like many rural towns that have long depended on revenue from the coal industry, Gillette could be walking toward a financial cliff amid plummeting coal prices and as a growing number of the nation’s coal-fired power plants shut down. Since 2008, coal production in the region has declined by half and coal mine employment has shrunk by a third. A University of Wyoming report projects that the state’s coal mining industry will lose nearly a quarter of its customer base in the next decade.

“You would think Gillette would show up as a disadvantaged community because of the economic impacts they’ve had due to changes in coal markets,” Kara Fornstrom, director of the University of Wyoming School of Energy Resources’ Center for Energy Regulation and Policy Analysis, told Wyofile. “But they don’t show up because a lot of the screening factors are per-capita income compared to the national average.”

Federal officials and environmental justice advocates, however, say the situation is not that simple.

Biden created Justice40 through executive order in 2021 as part of his broader effort to address the nation’s persistent socioeconomic and health disparities. It directs federal agencies to deliver 40 percent of the “overall benefits” of their environmental and energy investments to “disadvantaged communities that have been historically marginalized and overburdened by pollution and underinvestment.”

The directive has broadly compelled federal agencies to prioritize so-called disadvantaged communities when awarding grants for clean energy or environmental projects—sparking a national debate over which communities should be included in that definition.

The White House has developed an online tool to identify those communities but has been criticized by some activists who say the tool leaves out important demographics. tool’s methodology, saying it excludes middle-class Black families who live in disproportionately polluted neighborhoods due to racist policies like redlining. He promised to “fight just as hard” for any ailing rural Wyoming community that gets left out like those Black families were.

But Maria Lopez-Nunez, another member of the White House advisory council, said Justice40 isn’t meant to help just any community currently experiencing economic turmoil. While many rural areas have begun to face financial hardships in recent years, Lopez-Nunez said, the point of Justice40 is to help communities that have been historically overburdened by pollution and disenfranchised from political power and wealth. “What we’re trying to do with Justice40 is fix old legacy issues,” she said. “It’s not meant to address what might happen when we move away from fossil fuels.”

By definition, Lopez-Nunez added, Justice40 only accounts for 40 percent of the federal clean energy funding, meaning 60 percent remains for municipalities that fall outside the current scope of the program. Various federal agencies also interpret Justice40 slightly differently, meaning there is some flexibility in the way they reward their grants and who they decide qualifies to receive them, said a spokesperson for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 8 office, which oversees Wyoming.

The Department of Energy, for example, uses its own screening tool with its own set of metrics to identify disadvantaged communities, the EPA spokesperson said. And both the DOE and the EPA have expressed a willingness to award funding related to environmental justice to communities that aren’t initially identified as “disadvantaged” but provide compelling reasons for receiving the grants, the spokesperson added.

In fact, the Biden administration has anticipated that the clean energy transition would harm coal communities and has set aside federal funding specifically for that issue. Earlier this year, federal officials announced new policies that aim to ensure that rural regions hit by mine closures and shuttered power plants can get an economic boost from new federal energy and infrastructure funding. Those policies include access to nearly $38 billion in existing federal funding that coal communities can use to build new infrastructure, reclaim old industrial sites, and revitalize their economies.

The Department of Energy, for example, announced $450 million from the infrastructure law that can be used to build clean energy projects on current and former mine sites.

“Coal workers and residents in energy communities have been the backbone of the American economy for decades,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in April, announcing the new policies, “and they must be at the center of our nationwide economic investment.”