Amy Coney Barrett Is the Least Experienced Supreme Court Nominee in 30 years

Mother Jones illustration; Getty; Zuma/Images from left: Win McNamee/Zuma, Michael Reynolds/CNP/Zuma; Karen Bleier/Getty, Getty

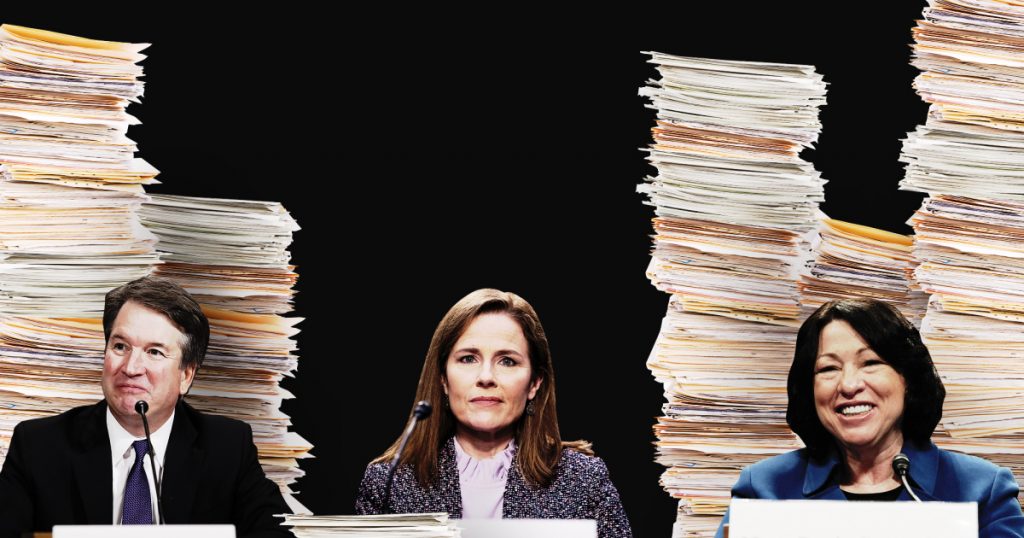

For indispensable reporting on the coronavirus crisis, the election, and more, subscribe to the Mother Jones Daily newsletter.Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett took some heat from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) during her confirmation hearing last week, when he pressed her on her failure to turn over additional relevant documents to the committee, including an anti-abortion newspaper ad she’d signed in 2006. Barrett responded that she had submitted 30 years’ worth of material to the committee, and that she had simply missed the 15-year-old ad. “I produced 1,800 pages of material,” she insisted, implying that this submission was voluminous.

In the world of Supreme Court nominees, however, 1,800 pages of documents barely registers as a footnote. Chief Justice John Roberts rustled up 75,000 pages of records for his 2005 confirmation hearing—just from his time serving in Republican administrations. The Senate reviewed about 170,000 pages of records before confirming Justice Elena Kagan and 180,000 for Justice Neil Gorsuch. No one even comes close to the document dump from Justice Brett Kavanaugh. The Senate Judiciary Committee waded through more than 1 million records during his 2018 confirmation fight, including a supplemental submission of 42,000 the night before his hearing started.

Page counts, of course, are not a perfect proxy for experience, but the relative paucity of Barrett’s is an indication of just how circumscribed her legal experience has been compared with virtually all of her predecessors—and even one nominee who was ultimately denied the position. The permanent record of the 48-year-old former Notre Dame law school professor is in direct proportion with her resume, which is strikingly thin for someone nominated to a lifetime position on the Supreme Court. By almost any objective measure, Barrett is the most inexperienced person nominated to the Supreme Court since 1991, when President George H.W. Bush nominated Clarence Thomas, then just 43, to replace the legendary Thurgood Marshall.

Barrett’s limited CV did have an upside: It’s one reason that Republicans have been able to rush her confirmation hearings and vote on her nomination, which the Judiciary Committee did Thursday without a single Democrat in the room. (The full Senate will vote on it Monday.) There’s simply not that much in her record to review.

But Barrett’s insular professional history raises some pertinent questions about her nomination that go beyond how she might rule on hot-button social issues: How did a professor from a second-tier law school with such a shallow reservoir of experience manage to leapfrog to the top of the list of potential Republican Supreme Court nominees? And why were Republicans, who have spent decades obstructing legislation that would help women advance in the workplace, so eager to promote this particular under-credentialed, female candidate?

“How did she go from really good law professor to the short list?” asks Angie Maxwell, a political science professor at the University of Arkansas who studies conservative politics and feminism. “That’s not from being a law professor. That’s from partisan networks and groups she worked with, and that’s what’s concerning.”

Barrett has spent virtually all of her professional life in academia. Until President Trump nominated her to the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2017, she had never been a judge, never worked in the government as a prosecutor, defense lawyer, solicitor general, or attorney general, or served as counsel to any legislative body—the usual professional channels that Supreme Court nominees tend to hail from. A graduate of Notre Dame law school, Barrett has almost no experience practicing law whatsoever—a hole in her resume so glaring that during her 7th Circuit confirmation hearing in 2017, Democratic members of the Senate Judiciary Committee were dismayed that she couldn’t recall more than three cases she’d worked on during her brief two years in private practice. Nominees are asked to provide details on 10.

Barrett has never tried a case to verdict or argued an appeal in any court, nor has she ever performed any notable pro bono work, even during law school. The ABA’s code of professional responsibility says lawyers should aspire to provide 50 hours a year of free legal services, with an emphasis on serving the poor in recognition of the fact that “only lawyers have the special skills and knowledge needed to secure access to justice for low-income people.” Chief Justice John Roberts famously met some of these requirements by representing a mass murderer on Florida’s death row.

In response to the Senate Judiciary Committee’s questions about her pro bono work, Barrett said she probably helped with such cases during her two years in private practice, but she couldn’t recall any details. Instead, she described her family’s participation in Angel Tree drives and volunteer work at a local soup kitchen—worthy projects undertaken by families all across America but not even close to the official definition of pro bono work.

Yet Barrett’s name was already being bandied about as a Supreme Court candidate almost as soon as Trump took office. She didn’t make the list of potential Supreme Court candidates his campaign released during the 2016 campaign, probably because she’d never been a judge. The president fixed that problem in 2017, when he nominated her for a seat on the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. The American Bar Association deemed her well-qualified for the post, and within three months of her investiture in 2018, White House officials were interviewing her to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy.

By comparison, the American Bar Association had reservations about Brett Kavanaugh when George W. Bush nominated him (for the third time) to serve on the DC Circuit in 2006—his inexperience and his “sanctimonious” performance during oral arguments counted against him. But by the time Trump picked him to replace Kennedy, he had spent 12 years on the appellate court and written hundreds of opinions. Trump’s other appointee, Justice Neil Gorsuch, had been an appellate court judge for 11 years before Trump nominated him to fill the seat vacated by the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Justice Sonia Sotomayor had been an assistant district attorney in New York City, a solo practitioner, and later a corporate litigator and law firm partner. She had been a federal judge, first at the trial court level, and then on the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, for 17 years before Obama tapped her for the Supreme Court.

Not all Supreme Court justices have logged decades on the lower courts before moving up the ladder. The late Chief Justice William Rehnquist, for instance, had never been a judge when President Richard Nixon appointed him. Barrett’s defenders often compare her to Justice Kagan, who also came to the court after working mostly in academia. Kagan had never been a judge, but she had wide-ranging legal experience when President Barack Obama nominated her in 2010, including significant public service experience. In 1993, she took leave for a summer from her teaching position at the University of Chicago law school to serve as special counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee. Her job there? Working on the Supreme Court nomination of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the legendary feminist Trump chose Barrett to replace.

Kagan later spent four years working in the Clinton White House, first as associate White House counsel and later at the domestic policy counsel. Clinton nominated her to a seat on the DC Circuit in 1999, but the GOP-led Senate never acted on the nomination. When Obama tapped her for the Supreme Court, critics complained that Kagan, like Barrett, had never tried a case. But unlike Barrett, Kagan had no trouble satisfying the Judiciary Committee’s questions about the most notable 10 cases she’d worked on in private practice at the Washington, DC, law firm Williams & Connolly before she went into academia. At the time of her nomination, she was the solicitor general, the first woman to hold the post, where she argued frequently before the Supreme Court, wrote briefs, and oversaw the work of nearly two dozen lawyers before the high court.

As for Kagan’s 15 years in academia, she wasn’t just any law professor, teaching three classes a year as Barrett did during her 15 years as a full-time law professor. In 2003, Kagan became the first female dean of Harvard Law School, where she had also studied. At the nation’s largest and most prestigious law school, Kagan oversaw a $400 million capital campaign, an operating budget of $180 million, and 500 employees.

Even Harriet Miers had a more substantial legal background than Barrett. Miers was the last woman a Republican president tried (though failed) to put on the high court. Then more than a decade older than Barrett is now, she was White House counsel for President George W. Bush when he nominated her in 2005 to replace retiring Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman on the Supreme Court. Conservatives ultimately torpedoed her nomination because they thought she’d go all wobbly on abortion or other conservative litmus-tests issues, much the way they believed George H.W. Bush’s nominee Justice David Souter did. Miers had once been a Democrat and conservatives attacked her credentials, suggesting that while she’d litigated and argued a host of cases in federal and state courts, they weren’t the right kind of cases. (Flash forward to Barrett, who has never litigated anything in federal court.)

The fight over her failed nomination obscured Miers’ rather impressive resume. Though never a judge, she had been a trailblazer in Texas, where she was the first woman hired at the big firm now known as Locke Lorde—and eventually its first female president. She was the first woman to head the State Bar of Texas. At one point, she even served as a witness in a sexual discrimination case against her own firm—the sort of experience Ginsburg might have appreciated in a colleague.

Outside the courtroom, Miers had a rich record of civic involvement and public service reminiscent of O’Connor’s, including serving two years on the Dallas City Council. And Miers did a considerable amount of real pro bono work, including representing a poor, single mother of six, with a ninth grade education, appealing all the way to the Supreme Court in a fight over disability benefits. (The court declined to hear the case.) When Bush was elected governor, he tapped her to clean up the troubled Texas Lottery Commission. Miers went to the White House with Bush, where she served as staff secretary, deputy chief of staff, and counsel to the president—the second woman ever to hold that post.

A recurring theme among Republicans is that Barrett is also something of a trailblazer—not because of any of her professional accomplishments or teacher-of-the-year awards, but because she will be the first woman on the court with school-aged children at home. “As a nominee for our nation’s highest court, Judge Barrett is an example to girls and young women in Iowa, and across America, that they truly can do it all,” Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) said after Barrett was nominated.

When President Trump took office, he immediately prioritized the federal judiciary in a way no other president has. To help him fill the bench with religious conservatives, he turned to the Federalist Society, a conservative legal organization established in 1982 that over the years has been funded with millions of dollars in dark money donations in an effort to stack the federal courts with conservative and libertarian judges for decades to come.

By July 2020, the group had helped the GOP-controlled Senate ram through a record 218 Trump judicial nominees—85 percent of them white, and 76 percent male. Its singular focus on youth and ideological purity among the nominees has been instrumental in lowering the standards for judicial office.

Trump has nominated 10 judges that the American Bar Association rated as unqualified to serve on the federal bench; seven of them were confirmed. Among those unqualified nominees was Brett Talley, an amateur ghost-hunter from Alabama who had blogged favorably about the Klan. (He withdrew from consideration.) And then there was Matthew Peterson, an elections lawyer nominated for a seat on the US District Court for the DC Circuit. The ABA rated him as qualified, but he withdrew his nomination shortly after his confirmation hearing, where he couldn’t answer questions from Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.) about basic legal concepts.

“They certainly value ideology and fidelity over traditional notions of careerism, qualifications and experience,” says Amanda Hollis-Brusky, a politics professor at Pomona College and the author of Ideas With Consequences: The Federalist Society and the Conservative Counterrevolution. “Their idea of someone who is a good judge is someone with a particular ideology, not someone who understands the craft.”

Lowering the standards for judicial nominations has benefitted a lot of mediocre men, but it has also accrued to the advantage of a few smart conservative women like Barrett, whose family life has put them at a disadvantage in racking up the sorts of legal qualifications normally required of a federal judge. “The pool [of conservative women lawyers] is so small that someone with her relative lack of experience on the bench is on the top of the list,” says the University of Arkansas’ Maxwell. Indeed, in 2016, when Trump released his original list of 21 conservatives he’d consider for the Supreme Court, only two of them were women currently serving on a federal court.

Barrett first joined the Federalist Society in 2005 and then again in 2014, after which she set off on an extensive speaking tour sponsored by the conservative legal outfit—a tour that bears all the hallmarks of a political campaign, only one targeted at the unelected post of Supreme Court justice. Between 2016 and the time Trump nominated her to the Supreme Court this year, she spoke at nearly two dozen Federalist Society events across the country, with the group picking up $15,000 in travel expenses for her in 2018 and 2019.

Barrett is not the only conservative woman with a shallow CV to benefit from an assist from the Federalist Society. Sarah Pitlyk, a former Kavanaugh clerk who had previously worked at an anti-abortion legal nonprofit, is now a Trump-appointed judge on the US District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri. A unanimous committee of the ABA rated her unqualified for the seat, in part because of “a very substantial gap” in her resume.

During her confirmation hearing, Pitlyk explained that she had never taken a deposition or tried a case because she had arranged her schedule to spend more time with her four children. During her Senate testimony she described herself as “very fortunate” for having had the opportunity to work “at small firms with very accommodating and flexible colleagues who want the best for me and for my family in addition to the best for our clients. I have had the luxury of getting to be as protected as possible and as supported as possible by my colleagues.”

Would that all women lawyers were so lucky. The legal profession is tough on women in a way it is not on men, and those who succeed often do so at huge costs to their personal lives. A 2017 McKinsey study found that while women represented almost half of entry-level workforce legal jobs, only 19 percent of equity partners in the nation’s biggest law firms were women, and women were nearly 30 percent less likely than men to make the first level of partnership. Children are a major factor in the attrition rate.

It’s no coincidence that Sotomayor, Kagan, and Miers had expansive resumes but no spouses or children when they were nominated to the Supreme Court, even though all of the male justices are married with children. The late Justice Antonin Scalia had nine of them; Chief Justice Roberts’ 4-year-old son famously upstaged President George W. Bush by tap dancing through the press conference when Bush announced Roberts’ nomination. That’s one reason Republican members of the Senate Judiciary Committee couldn’t stop marveling about Barrett’s seven children during her confirmation hearing. Sen. John Kennedy even asked her who did her family’s laundry.

Clearly, one likely reason Barrett’s resume is so thin is precisely because she has seven children. Consider this: If she took all the paid family leave available to her while she was a full-time professor, she would have spent nearly two of the 15 years she worked at Notre Dame on leave. That’s not the sort of butt-in-the-chair performance expected of lots of lawyers, much less those on track for superstar status. She’s pulled off a work-life balance many liberal women lawyers would envy. And she’s done it at a conservative Catholic law school, within the confines of a patriarchal conservative religious movement that in many quarters still frowns upon working mothers, paid family leave legislation, contraception, and anti-discrimination laws.

“It’s striking because the Federalist Society has so few women, it’s not as if they are a pipeline to uplift women in general,” says Pomona’s Hollis-Brusky. Women like Barrett, she says, have “been granted these opportunities by men who approve of their life choices.”

Indeed, Barrett is aligned with a movement in which people like Fox News’ Tucker Carlson blame working mothers for the “decline” of men, or conservative Christian commentator and RedState editor Erick Erickson publicly condemns working mothers as bad for kids. Yet these same conservatives give Barrett a pass. Carlson, who once said he felt sorry for Elena Kagan because she was “never going to be an attractive woman” is over the moon about Barrett. “Amy Coney Barrett is a remarkable person, an unusual person, maybe the most impressive person to receive a Supreme Court nomination in memory,” Carlson told his 4 million viewers in September. She “represents everything that made this a great country.”

Historically, Maxwell says, the conservative movement has made an exception for women like Barrett as long as they are furthering its anti-feminist agenda. She compares her to another Catholic superwoman of the religious right, the late Phyllis Schlafly, mother of six, who worked full time to defeat the Equal Rights Amendment as part of her lifelong campaign to keep mothers out of the workplace.

“She’s clearly very intelligent,” Maxwell says of Barrett, but her nomination is reminiscent of the time when Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) was trying to find a woman to put on the 2012 GOP presidential ticket and emerged with Sarah Palin. The former governor of Alaska had five children, including one with Down syndrome. Barrett also has a child with a disability, as well as two kids she adopted from Haiti. Elevating a woman like Barrett, who’s managed to do it all, is one way the conservative movement likes to “thumb its nose at all of the things that women say are still obstacles,” Maxwell says. If one woman with many kids succeeds at the highest level of law and politics, she says, “it invalidates [the obstacles] for all the other women.”

Barrett also checks another important box for the religious right: Men who would like to see the Supreme Court overturn the landmark abortion rights case Roe v. Wade have long hoped to have a woman cast the deciding vote. “It washes away the stench of it being sexist if it’s coming from a woman,” Maxwell says. Having not just a woman but one with seven children poised to overturn Roe explains conservatives’ outsize enthusiasm for a nominee whose professional record falls short when compared with most Supreme Court justices. “That is really part of the symbolic strategy,” Maxwell says. “I can still have it all, adopt the babies, have all of the children, cherish life, and still have all the success that every woman wants.”