America’s Ultrawealthy Already Got Their V-Shaped Pandemic Recovery

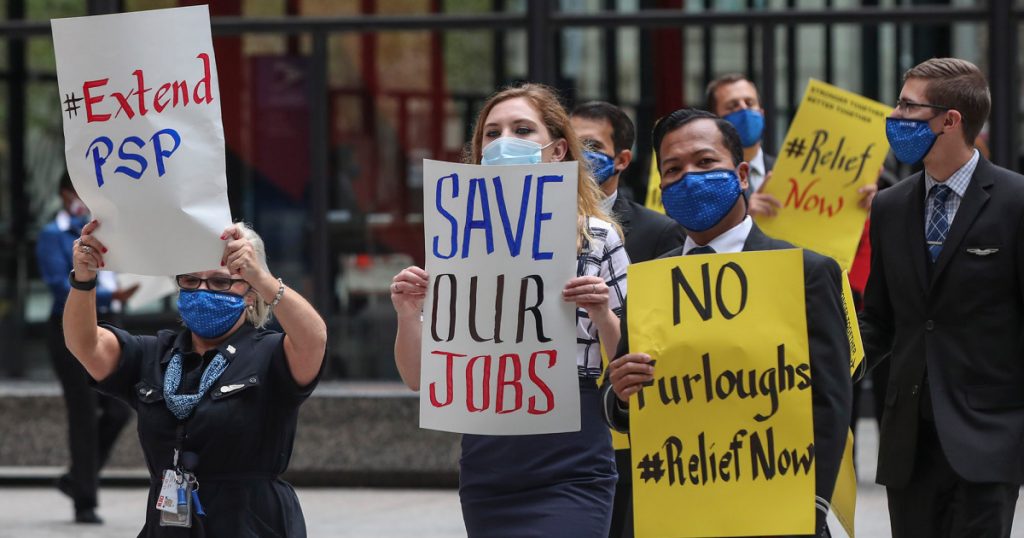

Airline workers in Chicago call for Congress to pass a new coronavirus relief package.Kamil Krzaczynski/Getty

For indispensable reporting on the coronavirus crisis, the election, and more, subscribe to the Mother Jones Daily newsletter.When America started going into pandemic lockdown back in March, the situation was scary and uncertain for rich and poor alike. The wealthy feared that their industries, investment portfolios, and personal fortunes would be greatly diminished. Low- and middle-income people feared that their jobs and pantries would dry up, that they would be evicted and foreclosed upon. With prospects now fading for a pre-election stimulus bill and the Trump administration’s promise of a V-shaped recovery yet to materialize, America’s most vulnerable remain fearful. But our richest citizens are enjoying a strong comeback.

Earlier this week, Wealth-X, an analytics firm that crunches data on the world’s most fortunate people, released its World Ultra Wealth Report 2020. The report covers 2019 mainly, but it includes a section on how ultra-high net worth individuals—those with net assets of $30 million or more—have fared during the pandemic.

Very well, thanks. Economically, things were looking pretty fabulous for this elite group before COVID came calling. As of 2019, the United States, with about 4 percent of the planet’s population, boasted more than 32 percent of the world’s ultrawealthy individuals. From 2016 to 2019, America’s ultrawealthy set grew by 28 percent, to 93,790 people, while their combined assets grew to more than $11 trillion—an even bigger increase.

Then came coronavirus. From the end of 2019 through the end of March 2020, Wealth-X reports, the combined ultrawealthy populations of the US and Canada plummeted by 23 percent. Almost 24,000 folks dropped out of that elite category. But the performance of the equities markets do not reflect the lived reality of most people, and those in the highest tiers tend to obtain most of their income from investments. When the markets rebounded, so did the most fortunate. By the end of August 2020, America’s ultra-high net worth population was back to where it was on January 1, and their overall wealth was down less than 1 percent for 2020—not bad, considering the previous year had been an unusually profitable one for this demographic.

At first, the pandemic threw quite a twist into the book I’ve been working on these past two years. Titled Jackpot, it digs into the experiences of America’s wealthiest citizens in an age of near-Dickensian economic inequality, and how our relentless urge to accumulate affects our society. Having done most of my reporting pre-COVID, I had to reconnect with all my wealthy sources to see how the crisis was affecting them. Some were understandably fearful for both their fellow citizens and personal fortunes, but it soon became clear that most would do just fine—if not exceedingly well, as so many of America’s billionaires have.

One source, the founder of a successful technology company that went public and was later acquired for more than $1 billion in current dollars, had just closed a fresh funding round on one of two startups he’d seeded. The other startup, a point-of-care diagnostics company, quickly pivoted to COVID testing. “We got lucky,” he said, and more personally, “as it turns out, I had a lot of cash.” So his financial advisors were helping him find promising moneymaking opportunities in the down market.

Another ultrawealthy source, whose industry faced an “existential” crisis, he told me, soon realized that the situation could prove very profitable for his private equity portfolio (so long as his industry recovered within a few years). A third, who also had lots of cash on hand when the markets tanked in the spring, used the opportunity to invest in companies that stood to profit from the pandemic, and short-sold the broader market as a hedge, a play that may yet pay off.

According to Wealth-X, nearly 38 percent of the wealth held by the planet’s richest people is in liquid form: cash, income, and dividends. This liquidity, and ready access to capital, are among the perks of the well-heeled. They enable a person to pounce on juicy business opportunities even as the underlying economy is screwing the pooch.

The government has taken care of the wealthy, too. Lobbyists slipped provisions into the CARES Act that amount to a tax break of more than $160 billion that will largely benefit the kinds of folks I’ve been interviewing. “Nice provisions,” one responded when I described the new tax breaks; “What the fuck?” replied another. I called up Steven Rosenthal, a tax attorney and senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. Rosenthal, who used to work for Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, was vehemently opposed to this bailout for the ultrawealthy. “The owner society is really doing quite well through the government’s help,” he told me. “The way I look at it is you’ve got capitalism for gains and socialism for losses.”

The privileged few who can afford to hire lobbyists were “genuinely scared about losing businesses and wiping out a good chunk of their fortune. I understand that,” Rosenthal added. “But their fright is not the same kind of fright as people who are going to be thrown out on the street.”