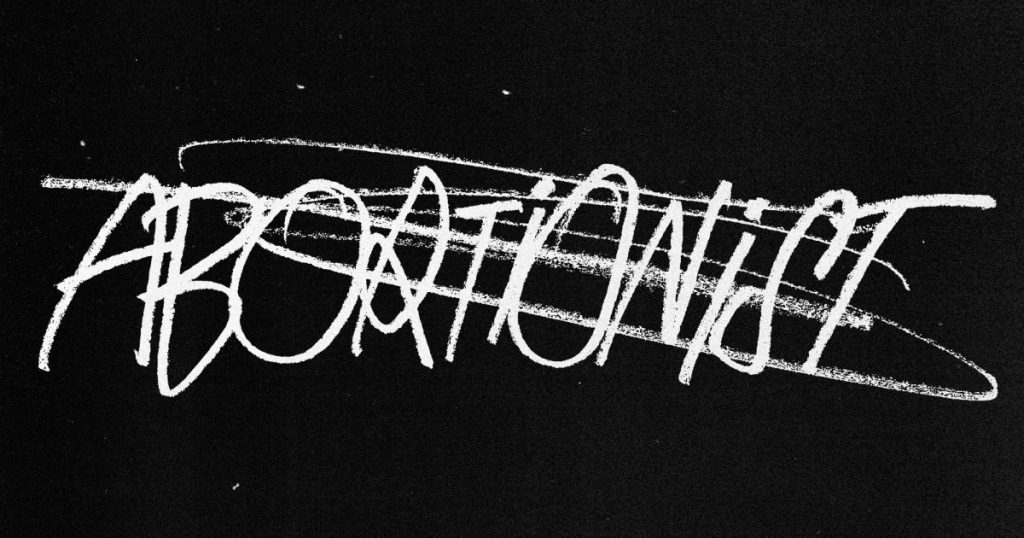

“Abortionist”: The Label That Turns Healthcare Workers Into Criminals

Bráulio Amado

Fight disinformation: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter and follow the news that matters.In 2007, after Paul Ross Evans pleaded guilty to leaving a bomb outside of a women’s health clinic in Austin, he assured the judge: He never meant for anyone to get hurt. “Except,” he clarified, “for the abortionists.”

For almost two centuries, the moniker “abortionist” has branded those who help terminate pregnancies as illegitimate, dangerous, and, in turn, allowable targets of violence. Before Roe v. Wade, the label turned midwives and doctors into criminals to be cracked down on by the state. After the 1973 decision, right-wing movements continued to deploy the term to imply only back-alley doctors performed abortions.

In 2022, the sobriquet showed up once more in the halls of power: “Abortionist” was used four times in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, channeling a fraught history.

Until the late 1800s, abortion and reproductive health were primarily handled by women—midwives, many of whom were Black, Indigenous, or immigrants. As medicine professionalized, male doctors viewed this skilled group as a threat to their business. Birth, they argued, ought to take place in a hospital. “The midwife is a relic of barbarism,” Dr. Joseph DeLee, a prominent 20th century obstetrician, proclaimed, “a drag on the progress of the science and art of obstetrics.”

The restructuring of gynecological medicine went hand in hand with a budding movement to criminalize abortion. In 1860, governors of every state received a letter from the president of a young organization, the American Medical Association. Ghostwritten by Horatio Storer, a Harvard-educated surgeon, the letter was part of an AMA campaign touting a new idea: Abortion should be illegal because life begins at conception—not, as previous laws considered, at “quickening,” when fetal movements are first detected. Under this logic, as Storer made it his mission to convince the masses, practically all abortions should be a crime.

A key part of the propaganda was to insist most abortions could not be health care. Following an 1864 AMA meeting in New York, Storer took up the argument in a famous essay. If a “practitioner of any standing in the profession has been known, or believed, to be guilty of producing abortion, except absolutely to save a woman’s life,” he explained, the physician “immediately and universally [would be] cast from fellowship, in all cases losing the respect of his associates.” The message was clear: We are doctors and they are abortionists. (The AMA awarded Storer its Gold Medal for the article.)

His argument prevailed. During the late 1800s, statehouses wrote new legislation banning abortion, police stations filled with local practitioners offering the procedure, and newsrooms took up the cause, relegating reproductive care to the crime blotter. (The first known usage of “abortionist” comes courtesy of an 1843 article in the New York Herald noting the arrest of Madame Costello—known for her euphemistic newspaper ads for women, promising to help “those who wish to be treated for obstruction of their monthly periods.”) By the early 1900s, abortion was illegal in every state.

More than a century later, we’re once again in an era of reproductive criminalization, and “abortionist” has reemerged in prominent places. In an April 2023 ruling that stayed the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone, US District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk mentions the term 11 times. Last year, Fox News called doctors “late-term abortionist[s].” And Southern Baptist Convention President Bart Barber wrote, following Dobbs, that “the abortionist is the murderer.”

A moniker that supposedly condemns violence is being used once more to condone it. In this landscape, anyone who—to borrow the language of Texas’ restrictive law—“aids or abets” abortion can be seen as an abortionist.

Grace McGarry was at work in the Texas clinic the day Evans planted the bomb there. She was not performing surgeries; she was a patient advocate. Yet, the explosives could have killed her, too. “Oh, he means me,” she later realized, after Evans told the court he had wanted to hurt the abortionists. “He doesn’t just mean my doctors. He means me.”