A Tribute to My Improbable Tea Party Friend

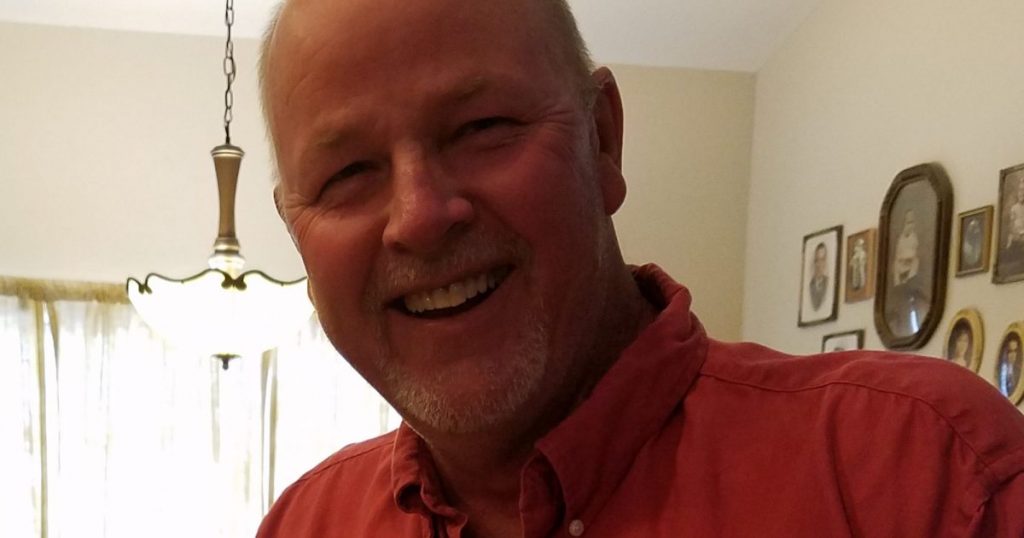

Robin Stublen, on his birthday last year, before he was diagnosed with cancer.Courtesy of the Stublen family

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

On paper, Robin Stublen and I should never have been friends. He was a Donald Trump-supporting self-identified redneck who hated Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, thought liberals were ruining the country, was deeply offended by NFL players taking a knee during the national anthem, and supported oil drilling off the coast of Florida, where he lived. I am a bleeding-heart liberal who fears what Donald Trump is doing to the country, thinks it’s about time that political protests hit the NFL sidelines, and abhors oil drilling off the coast of Florida, even though I don’t live there and never will.

Improbably, though, we were friends, at least until this month: Robin died on December 19 at the age of 61.

Had my exposure to Robin been limited to internet communications, surely we would have hated each other. As the returns came in showing Trump winning the presidential election, Robin wrote on his Facebook page, “Folks that sound you hear is the jet engines warming up to take all those liberal sons-of-bitches the hell out of this country!!” But behind every random and divisive Facebook posting is a human being, and Robin was a complex and endearing one.

I first talked to Robin in 2009, when I was covering the burgeoning tea party movement and he was one of its original organizers. He had unsuccessfully run for office a couple of times in Charlotte County, Florida, but at the time he joined the tea party, he told me he “mowed lawns and killed bugs” for a living.

My employment at Mother Jones served as interview repellent for grassroots tea party types, so I had trouble getting some of my subjects to talk. But Robin talked, and he kept talking to me for the next eight years. His chattiness stemmed in part from that fact that he represented the ideals of the tea party in its purest form: He hated the establishment in both political parties, thought the government spent too much money, and was interested in exposing corruption regardless of where he saw it. Accountability, for him, was to be applied equally to libtards and to his fellow anti-Obama crusaders.

In the beginning, most of this talking was work for me. But as I got to know Robin, we started discussing kids and spouses, trading pet and vacation photos, and bonding over our frustration with the high cost of college tuition. And then this spring, within a week of each other, we were both diagnosed with cancer, and suddenly our political differences seemed impossibly small, and our friendship so much bigger.

“There’s only one rule: No cussing,” Robin warned a group of tea partiers who’d assembled for an open mic rally in Punta Gorda, Florida, in 2010. It was unusually cold and rainy that day, and the rally was attended by only about two dozen people, mostly elderly and seated on lawn chairs. After ceding the mic to a guy who launched into a long-winded call for auditing the Fed, Robin looked out at the gathered activists and conceded to me with a laugh that his demographic skewed a little gray. It did not have the trappings of the “angry mob,” as the tea party was often described, he acknowledged.

Robin had invited me to visit to see the tea party at work, and I met him in person for the first time on that trip. Then in his early 50s, he was a big guy, solidly built and mostly bald. Robin was originally from West Virginia but loved his adopted state, even though he hated the beach. He gave me a grand tour of Punta Gorda, which had been almost entirely flattened by Hurricane Charley six years earlier. Driving around town, Robin provided running commentary on all the places that had recently been rebuilt. He explained what it was like to live through the storm and talked about his involvement in the disaster response.

It was then that I decided Robin would be the world’s greatest neighbor. At Christmas time each year, he put up around 350,000 lights on his house in such a fantastic holiday display that people would drive from all over the county to see it. He eventually put out a donation box, and over five years raised $12,000 that he donated to the local Kiwanis club.

For the next seven years, we stayed in touch, even as the tea party fizzled out. He sent me tips about fraudsters and railed against the deep-pocketed groups that stepped in to co-opt his movement, including the Koch brothers, whose nonprofit Americans for Prosperity ended up putting a lot of Florida tea party volunteers on its payroll. Robin was authentic, and he believed in grassroots political action. He also lived modestly. His idea of an indulgence was taking his mom to Outback Steakhouse on Mother’s Day. The high salaries and expensive perks with which tea party leaders rewarded themselves as the movement expanded offended him.

I had long ago come to realize that despite my disagreements with him, he was a genuinely good man. So we just kept talking.Not all of his political activity burst with virtue. In 2010, he told me that President Barack Obama’s Organizing for America had posted online a “virtual” phone bank publicly listing all the names and phone numbers of Democrats who had voted in 2008 but didn’t vote regularly. Robin and other tea party activists had seized on it as a database for prank calls. They called Democrats and urged them to vote for extreme GOP Senate candidates like Nevada’s Sharron Angle and Delaware’s Christine O’Donnell. “Whenever I want a couple of giggles, I call the Democrats,” he said. “Why not? If they’re really that stupid, you gotta have fun.”

Robin eventually abandoned the tea party, but he also helped institutionalize it. He worked to help elect Rick Scott as Florida governor in 2010, and when Scott took office in 2011, he hired Robin to do constituent services and outreach. It was the perfect job for him, given his glad-handing skills. He agonized a bit about going to work for the government, which he’d spent so much time railing against. Ultimately, though, he told me he needed to get out of the sun. Years of working outdoors had given him pre-cancerous skin lesions, and his knee hurt.

He was initially an enthusiastic supporter of Scott, but he quickly found fault with the administration. Robin had high standards that most politicians seemed fatally doomed to fall short of, especially Scott, who made headlines six months into his first term when polls showed that he was the country’s most unpopular governor. His budget cutting took a toll on state residents that I documented in a Mother Jones cover story. Robin forgave me the rough treatment of his boss, and throughout 2014, we regularly handicapped Scott’s reelection odds. Robin was sure he’d lose to Charlie Crist, the Republican-turned-independent-turned-Democrat, but Scott pulled it out, and Robin continued to work for him doing communications in the state transportation department.

Politics was always our main currency, and we traded gossip about the insipidness of Marco Rubio, Robin’s home-state senator, even as we clashed about other things, like Obamacare. Politics aside, Robin was a true friend. We met in person only once, briefly, after my 2010 visit, but he never failed to send me holiday wishes and texted me to “eat MEAT” when I was sick. Once, he somehow discovered that I’d had an irregular EKG at a check-up and urged me to get it looked at because, he said, “You are the only liberal I really like.”

Trump tested our bond. In September 2016, I posted on Facebook a Mother Jones story about an ad Democrats had made for Hillary Clinton that featured an interview with Alicia Machado, the former Miss Universe whom Trump had called “Miss Piggy.” Robin responded with outrage, in part because her comments in the video were in Spanish, and he suggested that the Miss Piggy remarks might have been made up. His defense of Trump’s behavior ticked me off, so I asked him if he’d want his daughter to work for Trump. He replied, “Yes, without a doubt. My wife too if she wanted.”

I was appalled. For a host of reasons, that episode might have ended our friendship. It was the sort of conversation that’s been happening all over the country, wrecking Thanksgiving dinners, cleaving friendships and marriages. Instead, I realized that I didn’t want to live in an echo chamber, and Robin was a good defense against that. Besides, I had long ago come to realize that despite my disagreements with him, he was a genuinely good man. So we kept talking.

I did try to prod him out of his own information silo. For Christmas last year, I sent him a Mother Jones gift subscription, ensuring that he’d be inundated with fundraising requests from Planned Parenthood, the Sierra Club, and the Democratic National Committee for years to come. When the first issue arrived in February, with a cover story on the Trump resistance movement, he thought it was ridiculously funny. He texted me, “I saw the cover and had to laugh. You are a good friend. Not going to convert me or anything. :)”

I was never gladder that our friendship survived Trump than I was this spring, when, in a strange twist of fate, we were both diagnosed with cancer within weeks of each other—Robin with esophageal cancer and I with breast cancer.

I was never gladder that our friendship survived Trump than I was this spring, when we were both diagnosed with cancer within weeks of each other.When he told me the news, he knew his odds were not good. Robin was a realist. On the phone later, he cried and told me he loved me like a sister—though he acknowledged that he rarely talked to his own sister. I cried, too. A week later, I told him about my own cancer diagnosis, and from then on, we didn’t talk much about politics. Instead, we compared radiation notes and made inappropriate jokes about death and cancer that we couldn’t make with anyone else. Mostly we just talked about life, which suddenly seemed so much shorter.

Governor Scott personally ensured that Robin got the best medical care, for which he was grateful. But even so, his prognosis and ordeal were much worse than mine. Over the summer, he had surgery to remove part of his esophagus and stomach. He was connected to a feeding tube for months and denied the small pleasure of a good meal. Even so, he maintained a sense of humor and, much to my surprise, continued to worry about how I was doing. He texted me almost the moment I got home from the hospital after surgery. Robin checked in on me more than anyone else, including my parents, even though he was far sicker and more miserable than I was.

In September, Robin was able to shed the feeding tube just in time to jump into his new camper and evacuate for Hurricane Irma. I demanded regular updates, which he sent from the road. Fortunately, his house was spared. Once he got home, he was back on Facebook, denouncing the pantywaists bitching about the power company’s work after the storm:

Hurricane Irma hit on Sunday, September 10. It is now four soon to be five days later and people are pissing and moaning about not having electric.

Suck it up buttercup!!

Do you have any idea what these lineman are dealing with? Do you have any idea the conditions they are working in? They come from all over this great country. Many have never experienced this heat, humidity, mosquitoes before.

When we had hurricane Charley we were without electric for 14 days. No one complained. You know why? Most of the people had no roofs!! So if you have a home to go back to, if your home did not flood, if you did not lose everything, then STFU!

I was glad to see the fire had returned after his long summer struggle, which included radiation and chemotherapy treatments. Things seemed to be looking up for him. But about a month later, Robin came down with pneumonia, and while in the hospital, a scan showed that the cancer had spread to his liver. On November 17, he wrote to me, “I want you to be one of the first to know that I am terminal.”

He was devastated and especially worried about his family, particularly his wife Greta, a school speech pathologist to whom he’d been married and devoted for 35 years. Doctors would try immunotherapy, but the best-case scenario was that he’d get another 12 months; worst case, three or four. I asked if he had a bucket list. He didn’t. He only wanted to take his family to West Virginia to show them where to sprinkle his ashes. He told me he didn’t want a memorial service. I objected, suggesting he do it open mic-style, like the tea party rallies, and I told him I would come and bring my lawn chair like the old people. “You could,” he replied. “Of course you could use mine. I don’t need it.”

Robin after finishing chemo treatments in May 2017

I hoped to make it to Florida to see him, but as it turned out, he lasted barely a month. I last chatted with him the week after Thanksgiving, when he wasn’t able to eat anything because of his condition. And then, on Tuesday morning, I had a bad feeling. I realized that with all the chaos of the holiday season, I hadn’t checked in on Robin in two weeks, and he hadn’t contacted me, which was unusual. I went to Facebook to send him a message and discovered that he had died a couple of hours earlier.

After all these years of our odd-couple relationship, I’m still not really sure why Robin picked me as his friend, or why he chose to share his cancer journey with me the way he did. After Robin died, one of his friends posted on his Facebook page, “I know right now he is at the pearly gates arguing with St. Peter on how liberals should not be allowed in heaven.” But he’s wrong about that. Robin liked me, and I liked him. We were friends in a way that seems almost impossible in today’s climate, and my life has been so much better because of it. I will really, really miss him.