A Minnesota Killer and Serial Rapist Will Serve Less Than Six Years for the Murder of Lorri Mesedahl

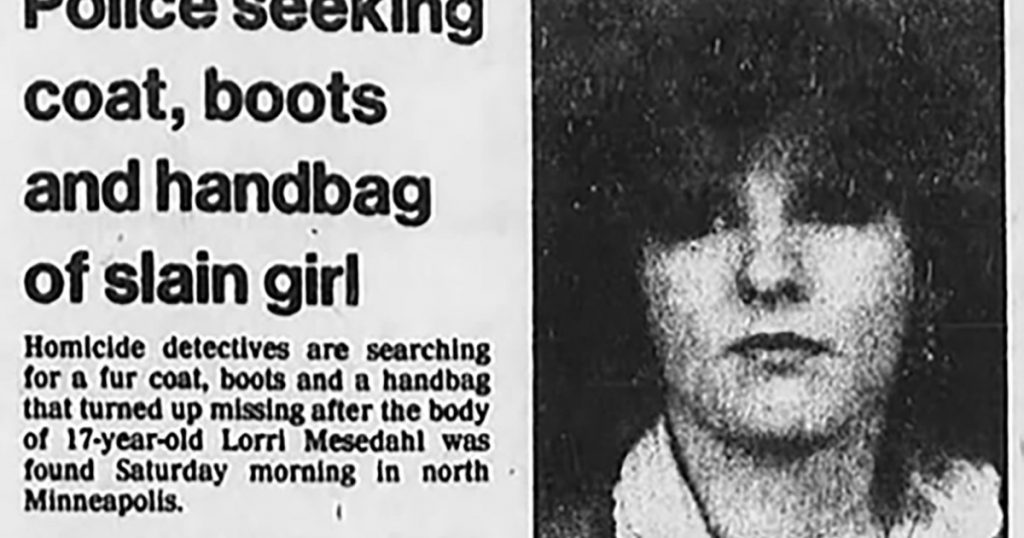

A Star Tribune article on Lorri Mesedahl’s murder in 1983.Newspapers.com

A Minneapolis murderer and serial rapist, Darrell Rea, slipped through the fingers of local law enforcement for decades after killing 17-year-old Lorri Mesedahl in 1983—sexually abusing his stepdaughters and raping two more women in the years that followed. On Tuesday, in Hennepin County District Court, Rea was sentenced to 10 years and one month in prison for the second-degree murder of Mesedahl with intent, under Minnesota’s sentencing guidelines from the early 1980s. He will likely serve just over five years before being released under supervision. He is 64 years old.

Rea denied involvement in Mesedahl’s death and did not express remorse in the courtroom. (Through his lawyer before the sentencing, Rea broadly denied the criminal accusations against him and declined to answer specific questions or comment further on allegations.)

As detailed in my investigation published this week, Rea could be not be charged for either the rapes of Barbara Briggs or Mary-Scott Hunter, even though there is DNA evidence linking him to the assaults, because of the three-year statute of limitations in effect when the attacks took place. (A similar situation is facing magazine columnist E. Jean Carroll, who last week accused President Donald Trump of raping her in a New York department store in the mid 1990s, according to former Bronx sex crimes prosecutor Roger Canaff.)

Hennepin County prosecutors also declined to charge the sexual abuse of Rea’s stepdaughters, Monique Stevens and Naomie Rondo, which started in the late 1970s.

“Darrell won the game,” said Del Young, Mesedahl’s stepbrother, through tears in his victim impact statement to Judge Tamara Garcia on Tuesday morning. “No matter what happens in this court here today.”

In coming to Rea’s guilty verdict last month, Judge Garcia considered evidence from the 1988 attack on Briggs, whom Rea raped and stabbed in the neck. Still, Briggs was not permitted to read her victim impact statement aloud in the courtroom this week, but she shared it in writing with the judge. “I have come to the conclusion I will never see justice,” she wrote. “This 10 year sentence is just enough to get him madder. A slap on the wrist.” She signed it: “scarred, sad, and feeling hopeless at times.”

Minneapolis Police Sergeant Chris Karakostas at the spot where Lorri Mesedahl’s body was found.

Madison PaulyStevens and Rondo, Rea’s stepdaughters, gripped each other’s hands tightly in the courtroom. They too submitted victim impact statements to the judge, but were not permitted to read the statements aloud. “I get out of bed every morning and tell myself I am going to face the day,” Stevens wrote. “I am not going to let this man define me. I am not going to let what happened to me, define who I am.”

“The abuse I suffered changed who I became and shaped my personality,” wrote Rondo. She added, “I am a fighter and refuse to let the abuse control me.”

Just before she read Rea’s sentence, Judge Garcia acknowledged their statements, telling the courtroom, “I would like all of you who wrote to me to know that I have heard each and every one of you.”

Hunter, who was raped by Rea in 1987, told me she is glad she did not have to deliver a victim impact statement in court. “I am not afraid to be vulnerable with people, but I consider it a sign of trust (or a leap of humanistic faith) when I am,” she wrote to me recently. “I believe that when folks are willingly and honestly vulnerable with each other, it’s a real gift. And, for obvious reasons, he doesn’t deserve that from me.”

Though Rea’s sentencing concludes the Mesedahl murder case, the law enforcement team that investigated the crime—and other crimes by Rea—isn’t done. “I think any investigator who worked, even touched this case, or knows anything about it, would agree that the probability that there are other victims out there, either living or dead, is probably pretty good,” Minneapolis Police Sergeant Chris Karakostas told me. As I detail in the investigation:

Now that Rea has been convicted of murder, he will be legally obligated to hand over a new DNA sample. And unlike the bloodstain from Briggs’ shirt, this one will be uploaded to the FBI’s national database. From now on, it will be automatically compared to unknown DNA from crime scenes across the country. When Rea’s DNA enters the system, Karakostas will be waiting to see if more hits come back from cases outside Minnesota. One day, he speculates, there could be another prosecution. In that future case, a judge could rule that the experiences of Hunter and Stevens count as corroborating evidence. Maybe they could still get some kind of day in court. “There’s a lot of women out there that really don’t have some justice for what happened to them,” Karakostas says.

Just before Rea entered the courtroom Tuesday, Karie Gibson, a member of the FBI’s behavioral analysis unit and part of the law enforcement team that worked on the Mesedahl case, leaned over to speak to me. “I don’t think today’s the last day we’ll be hearing about him,” she said.

Read the full investigation here.

This piece has been updated.