Blake Masters Is Peter Thiel’s Dream Candidate—and a Total Nightmare for Democracy

Facts matter: Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily newsletter. Support our nonprofit reporting. Subscribe to our print magazine.In the spring of 2012, Blake Masters, who was in his final year at Stanford Law, sat in on a computer science class taught by Peter Thiel, the billionaire co-founder of PayPal. During a lecture titled “Founder as Victim, Founder as God,” Thiel argued a kinglike leader was essential to innovation. “A startup is basically structured as a monarchy,” he explained. “We don’t call it that, of course. That would seem weirdly outdated, and anything that’s not democracy makes people uncomfortable.”

Afterward, Masters tweeted that the lecture was the best 90 minutes he’d ever spent in a classroom and linked to the exhaustive notes he’d been taking on Thiel’s course. For months, everyone from tech bros to New York Times columnist David Brooks headed to Masters’ Tumblr to read them. It was heady stuff for a CrossFit-obsessed libertarian described by a law school classmate as being “notable for not being notable.”

Masters was the perfect Thiel protégé. Both men attended Stanford and Stanford Law as proud iconoclasts who chafed at limits on their freedom. But while Thiel alienated dormmates by performatively downing vitamins as they nursed hangovers, Masters had the social skills to make friends in environments as ideologically hostile as the vegetarian co-op he lived in at Stanford. He had the ideal résumé to help a famously awkward billionaire popularize his unorthodox views.

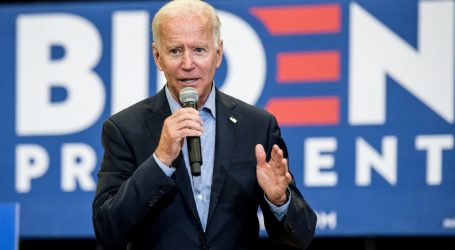

Blake Masters speaking with attendees at the “Rally to Protect Our Elections” hosted by Turning Point Action at Arizona Federal Theatre in Phoenix.

Gage Skidmore/The Star News NetworkMasters would never leave Thiel’s orbit. After finishing law school in 2012, Masters worked on a legal research startup with funding from his former teacher, co-authored a bestseller with Thiel based on the notes he’d taken from that class, and served as Thiel’s chief of staff and the president of his charitable foundation. Now, Masters is running for US Senate in Arizona with more than $13 million from Thiel behind him. If Masters wins his August primary, he will face Mark Kelly, the former astronaut and husband of former Congress member Gabby Giffords, in one of several races expected to decide which party controls the Senate.

Years ago, the two men’s focus on electoral politics would have seemed unlikely. Earlier in his career, Thiel wrote about creating floating colonies in the ocean, while Masters told people not to vote. Since then, both have had changes of heart about means, not ends. Instead of escaping state control, Masters and Thiel now hope to use its power to solidify the dominance of the founder class and end the technological stagnation they believe could lead to humanity’s extinction. To do so, they are willing to move fast and break things. But instead of disrupting taxi companies or hotels, American democracy is in their sights. A decade after his startup lectures, there should no longer be any doubt that Thiel’s sympathy for authoritarianism extends well beyond the private sector.

So he’s spending big to bend the American right to his will. He has also put at least $15 million behind Ohio Senate candidate JD Vance—another former employee, best known for his memoir Hillbilly Elegy—and helped arrange the Trump endorsement that secured Vance’s primary victory. In total, Thiel is supporting more than a dozen Republican candidates, most of whom have disputed the results of the 2020 election. And while he may soon have three senators whose rise he has helped fund—Vance, Masters, and Sen. Josh Hawley, another right-wing Stanford grad—it is Masters who would allow Thiel to effectively have a seat of his own.

Beginning in March, I sent repeated interview requests to Masters, who never replied. Last week, I sent him an extensive list of 24 fact-checking questions, which he also ignored. Thiel also did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Arizona voters who want to comprehend just how unusual Masters is must understand the full pantheon of his influences. They include Curtis Yarvin, who describes himself as America’s foremost absolute monarchist blogger; Murray Rothbard, the reactionary economist who suggested libertarians use right-wing populism to push their agenda; and Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, whom Masters has praised (with caveats). Another favorite is Lee Kuan Yew, the late dictator of Singapore who oversaw a miraculous economic transformation while crushing the civil liberties of those who stood in the way.

But no one is as influential as Thiel, who confessed in a 2009 essay, “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” He went on to warn that the “fate of our world may depend on the effort of a single person who builds or propagates the machinery of freedom that makes the world safe for capitalism.”

Thiel is setting himself up to be that builder. Masters is one of his tools.

In late April, Masters attended a candidate forum in the ballroom of Scottsdale’s Gainey Ranch Golf Club, a 27-hole oasis located on what was once an Arabian horse farm. Wearing a slim-cut navy suit, the 6-foot-3 former basketball player could have passed for a wealthy son visiting any of the prim seniors attending the event. The event’s emcee was a bald man whose LinkedIn profile mentions service in an “anti-terrorism” unit in Rhodesia’s white nationalist regime. To win, Masters would have to convince a primary electorate that skews white and geriatric that a thirtysomething who’d spent most of his adult life in California was the voice of Arizona Trumpism.

After dispensing with the requisite autobiography—raised in Tucson, married to his high school sweetheart, the father of three young boys—he pivoted to the doomsaying that has become his signature campaign spiel. “Conservatism can’t beat progressivism going the speed limit. You got to get people in there who know what time it is, who are going to play offense, because then and only then will we have a chance to save this, the greatest country in the history of the world,” Masters can be heard saying in a recording of the event. “Put me in in August and I guarantee you I will beat Mark Kelly by five points. Imagine me debating him as you’re listening to us tonight.” With that, it was time for the audience’s questions.

Asked about Kelly, Masters responded sarcastically. “‘Oh, I’m an astronaut. Have you heard I’m an astronaut?’” Masters said, imitating the senator. “‘You know, when I’m on the space station and I look at that big blue ball I realize we’re all in it together.’ And it’s like, ‘Shut up, Mark.’” The punchline had the crowd laughing. Such swaggering contempt is typical Masters, who speaks with the self-confidence of a man who has always considered himself to be exceptional and is unsurprised that the world agreed.

Over the course of the Q&A, Masters said he backed impeaching Joe Biden over his border policy, attacked generals for being too woke, and warned that Social Security and Medicare would disappear before his fellow millennials became eligible. “Sorry,” he said. “But plan for that now.” (According to the financial disclosure Masters submitted last year, much of his own substantial wealth was held in cryptocurrencies.)

Many of the more than a dozen friends and acquaintances of Masters I’ve spoken with, including the best man at his wedding, have been shocked to see the transformation of someone who used to consider himself an open-borders libertarian turn into an America First nationalist whom Tucker Carlson calls “the future of the Republican Party.” “He was not a shitty, hateful person,” says a former college roommate. “He was a misinformed libertarian white 20-year-old. But honestly, they were a dime a dozen at Stanford.” But even as a young man, there were signs that Masters would be almost uniquely suited to fall under the sway of an icon like Peter Thiel.

When Masters was 4 years old, his family moved to Tucson and settled in a gated community alongside one of Arizona’s best golf courses. His dad, Scott, had attended the Air Force Academy before joining the nascent software industry. His mom, Marilyn, would go on to run a Kumon tutoring center.

Masters got an early introduction to the progressive pedagogy he now loathes as a second grader in public school. Masters wrote a letter to a local paper stating his opposition to clearing desert land for new houses. His conservative parents saw it as evidence that their son was being indoctrinated with left-wing environmentalism. A couple of years later, they were frustrated when Blake was taught that Christopher Columbus was a racist who murdered Indigenous people.

Masters with Green Fields friends Collin Wedel and Noah Gustafson (left to right). Courtesy Noah GustafsonFor sixth grade, they enrolled young Blake in Green Fields Country Day School. At its founding in the 1930s, the school sought to merge East Coast elitism with West Coast frontier individualism: Boys lived in cabins, practiced on the shooting range, and were provided their own horses as they prepared for schools like Exeter and Choate. By the time Masters started in the late ’90s, Green Fields was co-ed with about two dozen kids per grade.

As an eighth grader, Masters experienced love at first sight when he met a girl named Catherine Chewning. The feeling was not mutual for a young feminist whose poetry in the Green Fields archives included lines like:

But you stayed hiddenUnder a layer of your manhoodAnd refuse to agreeSo I’m done trying to helpI’m leaving you to rot in your conceited mind

There’s no evidence that Catherine was writing about Masters, who she came around to in high school and married in 2012. Catherine now homeschools their three boys, and her family shares a backyard with her mother and stepfather, whose Facebook page is filled with liberal posts. One of the articles he shared last year was headlined “Elite Universities Have Promoted Destructive Republican Leaders.”

Masters and the best man at their wedding, Collin Wedel, also met in middle school, and others considered them the best students at a school full of bright kids. Masters was a popular three-sport athlete; Wedel was a sweet nerd. “You can find people who went to preschool with [Ted Cruz], who are like, ‘Oh, yeah, that guy was always an asshole,’” Wedel says, only slightly exaggerating. “That is not Blake.”

Wedel, a partner at a corporate law firm in California, says that when it came to politics, Masters was mostly interested in libertarian monetary policy, although he also wrote an op-ed for the school paper in favor of the Iraq War. In their senior yearbook, Green Fields faculty made tongue-in-cheek predictions about where the class of 2004 would end up. Wedel, they wrote, was going to be the Democratic nominee for president. “Unfortunately for Collin,” they added, “he will be defeated by Blake Masters, America’s first Libertarian President.”

Predictions from Green Field faculty in Masters and Wedel’s high school yearbook.

In his first year at Stanford, Masters made friends with many progressive students, including two women I’ll call Rebecca and Christina. (Both requested anonymity.) As sophomores, the three of them ended up sharing a room in Columbae, a left-wing vegetarian co-op where decisions were made by consensus. As the year progressed, Rebecca remembers Masters getting more and more militant about his libertarianism. “It became difficult to have meaningful conversations with him,” she says. “We were like, ‘Dude, Ayn Rand is supposed to be a phase.’”

Masters’ years in Palo Alto were in some ways comparable to Thiel’s. After coming to the United States from Germany as an infant, Thiel spent part of his childhood in apartheid-era South Africa, where his father oversaw engineers working on a uranium mine that was part of the regime’s secretive nuclear weapons program. The Thiels then settled in California, and Peter—a chess prodigy who was bullied by his classmates—went on to Stanford.

While there, he co-founded the conservative newspaper the Stanford Review, which was known for its “virulent” homophobia, as Max Chafkin reports in his Thiel biography, The Contrarian. One column argued that homophobia should be rebranded “miso-sodomy”—hatred of anal sex—to foreground “deviant sexual practices.” The author of the column, Nathan Linn, would go on to work for Thiel, who spent much of his life as a semi-closeted gay man. Several years after finishing Stanford Law, Thiel co-wrote a book, The Diversity Myth, that railed against progressivism at his alma mater, including its decision to provide benefits to LGBTQ employees’ domestic partners.

Like Thiel, Masters fought back against his peers with a mix of provocation, political purism, and disdain. In the one article he wrote for the Stanford Daily, Masters argued that voting is usually immoral because it leads to others being forced to pay taxes: “People who support what we euphemistically call ‘democracy’ or ‘representative government’ support stealing certain kinds of goods and redistributing them as they see fit.” He urged his fellow students not to participate in the 2006 midterms.

Masters moved off campus junior year but remained active in the Columbae community. For a co-op talent show that Masters was unable to attend during his senior year, he sent a video in which he rapped while wearing what was meant to resemble Native American war paint. “I’ve got the war paint on, as you can see,” he rhymed over a beat in the video, which was shared with Mother Jones. “Who said what about cultural insensitivity?”