Why the Green New Deal Is So Vague About Food and Farming

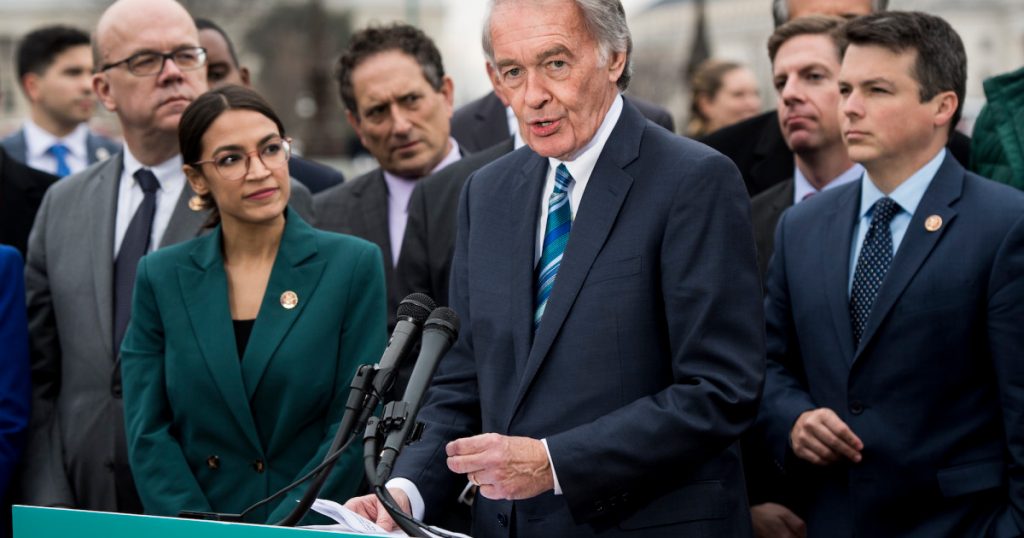

Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) hold a press conference on the Green New Deal outside of the Capitol on February 7, 2019. Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/AP Images

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

The Green New Deal resolution, released last week by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), offered broad visions for socially just and climate-ready food and farm policy. It called for a “10-year national mobilization” to “eliminate pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector” by “supporting family farming,” “investing in sustainable farming and land use practices that increase soil health,” and “building a more sustainable food system that ensures universal access to healthy food.”

These statements are undeniably vague, and that drew the ire of some observers. Washington Post food columnist Tamar Haspel took to Twitter to “give it a C, or maybe C-,” declaring the family farming and food access planks so vague as to be “basically meaningless” and the soil health piece to be “on target but really broad.”

Tech investor Ramez Naam noted in a widely shared Twitter thread that the document “does talk (vaguely)” about reducing farm-related greenhouse gas emissions, which is “better than nothing.” But then he dropped the hammer: “[I]t’s one and only proposed solution—local ag—is a non-solution.” It was an odd critique, because the resolution’s tiny agriculture section makes no mention of local farming. Naam then lays out what he thinks should be in the document. (Note: ARPA-A is a reference to the US Department of Defense office whose research led to the development of the internet.)

What would climate policies focused on agriculture & industry look like?a) An ARPA-A in the Dept of Ag, driving science to remove methane from livestock & otherwise tackle ag & deforestation.b) Incentives for farmers to adopt new tech to reduce methane & other emissions. 17/

— Ramez Naam (@ramez) February 9, 2019

But here’s the thing: Both Naam and Haspel miss the point. The Green New Deal, in its current form, isn’t about rolling out policy proposals that are “politically feasible,” as Haspel put it in a tweet in response to mine, or as Naam put it, “actually passable.”

I don’t think there’s a shortage of NGOs or food justice groups suggesting policy. The problem is weeding through those ideas to find ones that are A) effective and B) politically feasible.

— Tamar Haspel (@TamarHaspel) February 7, 2019

Last week’s Green New Deal document doesn’t aim to be a set of policies ready to sail through the current Congress. Rather, it’s a resolution that, as its very first line puts it, recognizes the “duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal.” It’s a set of policy goals—ones that are, by design, quite ambitious: “net-zero greenhouse gas emissions through a fair and just transition for all communities and workers,” “to create millions of good, high-wage jobs and ensure prosperity and economic security for all people of the United States,” and more.

But it is bluntly agnostic on what policies should be put in place to achieve these goals, stipulating that they should emerge “through transparent and inclusive consultation, collaboration, and partnership with frontline and vulnerable communities, labor unions, worker cooperatives, civil society groups, academia, and businesses.” Filling in the blanks of what specific legislation is to come out of the deal is left up to the public.

This is an extremely unusual strategy for US politicians. Normal legislation involves a congressperson proposing “politically feasible” or “passable” policies and then trying to push them through the bill-to-law process. But Ocasio-Cortez and Markey seem to be acknowledging that the standard strategy has stalled when it comes to climate change. What is politically feasible when climate deniers control the presidency and the Senate? What’s passable when the oil and gas industry showers Washington, DC, with more than $66 million in campaign cash every two-year election cycle?

Ocasio-Cortez and Markey’s idea is to generate an upswell of grassroots support for policies that aren’t feasible under President Donald Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.)—but might soon be if the political tides change. And the way they seek to drum up that support is to consult the public directly for policy ideas, building buy-in as they go. The outside-inside strategy also explains why Ocasio-Cortez is keen to mount primary challenges against Democratic colleagues whose campaign contributions might make them reluctant to support bold climate action. “All Americans know money in politics is a huge problem, but unfortunately the way that we fix it is by demanding that our incumbents give it up or by running fierce campaigns ourselves,” Ocasio-Cortez said on a conference call with supporters last year. “That’s really what we need to do to save this country.”

Will the Green New Deal strategy work? No one has any idea. But the old tactic of pushing feasible climate legislation through Congress has little to show for it. Back in 2009, Markey (then a member of the House of Representatives) mounted a massive effort with then-House colleague Henry Waxman to push comprehensive climate legislation through the DC sausage machine, at a time when Democrats controlled the presidency, the House, and the Senate. After the Waxman-Markey bill, as it was known, narrowly passed in the House, it had quite a slog in the Senate, as Ryan Lizza showed in his wonderful 2010 New Yorker tick-tock. By the end of the process, Lizza reported, the bill’s Senate sponsors had “abandoned their attempt to cap the emissions of the oil industry and heavy manufacturers and pared the bill back so that it would cover only the utility industry”—and soon after watered down the cap on utilities, too. It failed anyway—and the Green New Deal is the Democrats’ first attempt at climate legislation since.

Agriculture policy too is paralyzed by big industrial interests, geared for decades now to encourage overproduction of a couple of chemical-intensive crops, polluting water and destroying soil in the process. Indeed, as my reporting showed at the time, Big Ag interests managed to exempt farming from Waxman-Markey’s greenhouse-gas emission cap even before the bill left the House.

“The influence of special interests is now at an extremely unhealthy level,” former Democratic presidential nominee Al Gore told Lizza in 2011, explaining the Waxman-Markey bill’s sad path to collapse. “And it’s to the point where it’s virtually impossible for participants in the current political system to enact any significant change without first seeking and gaining permission from the largest commercial interests who are most affected by the proposed change.”

So that’s the context for the Green New Deal. Rather than consult and gain permission from Big Ag and dirty energy before enacting climate legislation, they’re going straight to the public. I like Raam’s idea of setting up an ARPA-like research team within the Agriculture Department tasked with finding more climate-friendly farming techniques—even though it’s not likely feasible under current leadership. Let a thousand flowers bloom. I’ve been talking to various scientists, farmers, and activists in the sustainable agriculture, soil health, and food access spaces about what an effective Green New Deal could look like. I’ll report back soon.