Trump’s Not Richard Nixon. He’s Andrew Johnson.

For more than a century the official narrative of the first presidential impeachment has been butchered and distorted, reduced to a historical curiosity, a showdown between two irresponsible factions in which voices of reason ultimately triumphed. You were likely taught (if you were taught at all) that the 1868 fight to remove Andrew Johnson from office centered on an obscure and dubious law, the Tenure of Office Act, and that “Radical” Republicans—their influence inflated in the aftermath of the Civil War—overstepped their bounds in a quest for even more power.

This viewpoint was memorialized most famously in John F. Kennedy’s Pulitzer-winning 1957 book, Profiles in Courage, which canonized Edmund G. Ross, the Kansas Republican senator whose last-minute decision reversal led to Johnson’s acquittal. The verdict, as recounted by Kennedy, was a triumph of sobriety and institutional scruple, of country over party, of pragmatism over ideology. It’s all of the stories official Washington loves to tell about itself, wrapped in one: When both sides are to blame, real heroism can mean doing nothing at all.

At this point, it’s a cliché to compare President Donald Trump’s present predicament to Richard Nixon and Watergate—the pathetic desperation of the crime itself, the bungling attempt at a cover-up, the release of an incriminating transcript. Fair enough. But the best parallel to Trump isn’t Nixon; it’s Johnson, a belligerent and destructive faux-populist who escaped conviction by the thinnest of margins. Though popular critics like Kennedy have long framed the Johnson impeachment as a fight over something small—an act of legalistic nitpicking—the stakes could not have been bigger. It was about what kinds of transgressions and values were worth fighting over in a country that in many ways was still at war with itself. Sometimes the biggest crimes aren’t criminal at all.

Thankfully you don’t have to take JFK’s word for it these days. Brenda Wineapple’s The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation, published this spring, is a welcome rejoinder to the impeachment whitewashing. Wineapple places the trial of the 17th president in the context of the violence and political turmoil that built up to it. In her lively account of the road to impeachment, the process was rife with bumbling and paranoia (yes, on both sides), but nonetheless centered on a profound question: whether the nation would continue on its path toward a pluralistic democracy or revert to the white supremacist state that had existed before Fort Sumter.

Johnson was a sort of anti-Lincoln, a stumpy, vengeful, subliterate tailor who rose through the ranks of the Democratic Party in East Tennessee by railing against elites. In 1861, he was the only Southern senator to stay loyal to the Union, leaving him not only without a state but largely without a party. Lincoln appointed him military governor of Tennessee, and later, hoping to shore up his support ahead of his re-election campaign, added Johnson to his ticket. Johnson showed up drunk to his own swearing-in, then hid out at a friend’s house in Maryland, ashamed to show his face. A few weeks later, he was president.

At first, the so-called Radical Republicans—the vociferously anti-slavery lawmakers who had pushed Lincoln to pass the 13th Amendment and provided the strongest support for the prosecution of the war—were optimistic that Johnson would be an ally in their quest to reconstruct the South. Johnson had once told a group of freedmen that he would be their “Moses,” and he suggested in meetings early on that he would commit himself fully to enacting Lincoln’s agenda.

But alarm bells began to sound. Johnson was erratic. He was wavering. Frederick Douglass met with him at the White House and came away disturbed. In the meeting, the president had suggested deporting millions of freedmen and appeared to be unfamiliar with who Douglass actually was. Johnson started granting mass amnesties to Confederate soldiers and appointing Confederates to key governmental posts. In the summer of 1866, a wave of racial pogroms broke out in former cities of the Confederacy, targeting freedmen—34 killed in New Orleans; 46 killed in Memphis. Why hadn’t Johnson done anything to stop it? Why was he suddenly blocking every effort by Congress to bring white supremacist violence in the South under control? People who had once seemed enthusiastic at the project ahead were beginning to talk about the I-word.

Wineapple quotes Wendell Phillips, the Massachusetts anti-slavery activist, speaking after Johnson’s appointment of an ex-secessionist governor in Raleigh: “Better, far better, would it have been for Grant to have surrendered to Lee than for Johnson to have surrendered to North Carolina.”

There’s a lot about the Johnson impeachment that should feel familiar, because, as with Trump, undergirding the whole enterprise was an act of betrayal: The president’s loudest critics believed that he had sold out the country and its democratic institutions to a hostile power. In Johnson’s case, that power was the Confederacy. After five years of fighting, nearly a million deaths, and billions in unpaid debts, Johnson was restoring to power the enemy that had just been defeated. High-ranking Confederates were creeping back into positions of influence. Enemy agents—the Ku Klux Klan and its ilk, not FSB hackers—brazenly attacked the foundations of a free republic and terrorized freedmen while the president and his supporters downplayed their existence and enabled their work.

Then, as now, it was easy to fall down a rabbit hole. There was no Ritz-Carlton in Moscow, but members of Congress spent months searching for evidence that would implicate Johnson in the death of his predecessor. Rep. James Ashley (R-Ohio), a floor manager for the 13th Amendment, went searching for non-existent correspondence between Johnson and John Wilkes Booth. Rep. Benjamin Butler (R-Mass.), a crooked walrus of a man who would later serve as impeachment manager, wondered if the 18 pages missing from Booth’s diary might have implicated the president. The House investigated Johnson’s drinking. They asked if he was frequenting prostitutes. His behavior was just so inexplicable to them. There had to be some explanation.

And there really was some weird shit going on. Take the case of John Surratt. Although most of the Lincoln conspirators were quickly captured, convicted, and executed by military tribunals, Surratt somehow escaped to Canada and then to Rome—where he changed his name to “John Watson” and joined the Papal Guard.

The Johnson impeachment was fundamentally about values and power, and about what kind of country would emerge out of its greatest conflict. Plenty of people understood that bloodshed was the price of inaction, that there was nothing courageous about meek deference to power.You may be thinking, “Wait, is there another Papal Guard?” No, there is not. John Surratt was a Zouave. He wore a fez with a pom-pom on the end and big poofy pants and carried a musket, and when an American traveling abroad ran into him, Surratt fled to Egypt. He evaded capture for a year, long enough, somehow, for the statute of limitations to expire on kidnapping the president—the conspirators’ original plan, before they switched to murder. By then the military tribunals had been disbanded. He got a friendly jury in Confederate-curious Maryland and, by 1868, was a free man.

Strange, yes. Infuriating, very. But hardly, as Rep. George Boutwell (R-Mass.) suggested, evidence of a sinister plot. After all, the Lincoln conspirators would have assassinated Johnson too, if the man tasked with doing it hadn’t got drunk and lost his knife. There’s an Andrew Johnson in every group.

All of this chimes with our current conspiratorial moment . Unable to square what is happening with their understanding of how things are supposed to work, people start looking for totalizing explanations. They come to believe that the absence of smoke means someone must be covering up a fire, and that is never a good path to go down. That’s how otherwise well-balanced people wind up getting political news from Tom Arnold.

But there was only one true Johnson scandal, just as there is only one true Trump scandal, and though the particulars are very different—the former’s class resentment was the inverse of the latter’s class entitlement—they share a common element: an open hostility to democratic ideals. That was Andrew Johnson’s high crime, and there was nothing conspiratorial or nitpicky about it. He was doing it in plain sight. The rest was noise.

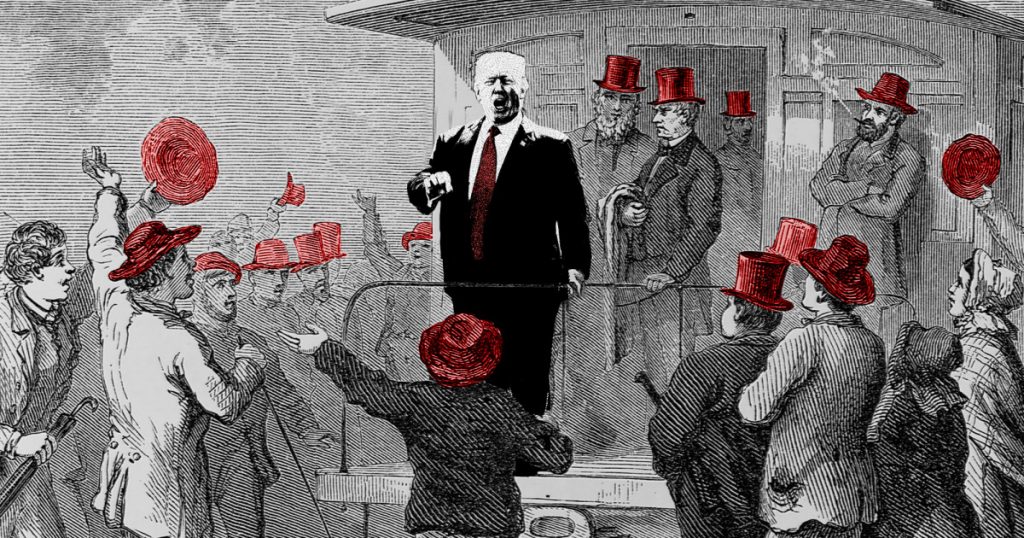

Mother Jones illustration; Library of Congress, Washington Post/GettyJohnson did not react well to all this chatter about his loyalties. In 1866, he decided to go on the offensive, embarking on a national tour to shore up his support. It was called the “Swing Around the Circle,” and it was insane. The closest I can come to describing is, maybe, what if George Wallace spoke at Altamont? It’s tough to find a true analogue. Presidents just don’t really talk like Johnson did on that tour, no matter what lurks in their hearts. Even Nixon didn’t talk like that, and Nixon hired a Jew-counter.

There are echoes of the Johnsonian aesthetic, though, in Trump. Suggesting that a political opponent should go back to her country has a Johnson-like ring to it. Smiling as a crowd chants “send her back” is a bit more like it. Casual cracks about political violence and treason, menacing libels of vulnerable classes, endless chatter about “lies” and “enemies,” a persecution complex big enough you could send the 13th Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry Regiment through it—that was the essence of the Swing Around the Circle.

Here, via Wineapple, is Andrew Johnson in St. Louis:

“I have been traduced and abused,” he shot back, his voice tremulous with self-pity. “I have been traduced, I have been slandered, I have been called Judas Iscariot,” he shouted. And just because he exercised his veto power over the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill or Civil Rights, his enemies said he ought to be impeached. The sympathetic members of the crowd cried out, “Never.”

“Yes, yes!” he answered, and then speaking of himself in the third person, cried, “They are ready to impeach him.”

“Let them try it,” his supporters answered back.

But he was incoherent. “There was a Judas once,” Johnson babbled, “one of the twelve apostles. Oh, yes! And these apostles had a Christ, and he could not have had a Judas unless he had twelve apostles.

“If I have played the Judas, who has been my Christ that I have played Judas with?”

It was bewildering. Again, he yelled, “Why don’t you hang Thad Stevens and Wendell Phillips?”

And they never show the crowd!

Johnson’s message, though, was disturbingly lucid: He was the only man standing between you and the mob, and you all know who the mob is. Phillips and Rep. Thaddeus Stevens (R-Penn.) should be hanged because they were ready to turn to the country over to the Black man while putting the white man in chains. He was saying, with his words and actions, that the tragedy of New Orleans and Memphis was that freedmen had tried to exercise power in the first place. These were the stakes.

Still, there was no rush to impeachment. It would take two more years of false starts before enough Republicans came around to the idea. For one thing, because it was untested at the presidential level and used sparingly anywhere else, no one really agreed on what constituted an impeachable offense. The Constitution said “high crimes” and “misdemeanors.” Okay—what are those? The handful of previous cases didn’t offer much help. One federal judge had been convicted of joining the Confederacy; another had been acquitted for, in Wineapple’s phrasing, “using rude language.”

Congress is an institution that craves structure. These are the people who invented the subcommittee. Stevens, a brilliant parliamentarian and Congress’ most ardent advocate for racial equality, cut through all of the agonizing with a simple answer: An impeachable offense is whatever the hell a majority of the House and two thirds of the Senate wants it to be.

“I do not hold that it is necessary to prove a crime as an indictable offense, or any act malum in se,” he said. In fact, Democrats who lamented that impeachment was being used as a political process were correct. It was! “I agree with the distinguished gentlemen from Pennsylvania, on the other side of the House, who holds this to be a purely political proceeding. It is intended as a remedy for malfeasance in office and to prevent continuance thereof.” But Stevens’ colleagues wanted a smoking gun, a clear legal infraction to hang their case on.

Things continued to get worse as Congress twiddled its thumbs. What eventually pushed Congress over the line was Johnson’s violation of a weird law called the Tenure of Office Act, which had been passed over presidential veto in early 1867 and prohibited the president from firing cabinet members without permission from the Senate. The law is a little arcane and was later found unconstitutional, but it responded to a real crisis.

Johnson’s secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, was appointed to the job by Lincoln. He was responsible for hundreds of thousands of soldiers throughout the occupied South and was the last line of defense for millions of freedmen trying to exercise their rights in the face of rising white supremacist terror—which, if Johnson had his way, the federal government would just ignore. Johnson wanted to get Stanton out of the way. This wasn’t really about checks and balances; it was a break-the-glass moment for Reconstruction.

The president abided by the law at first, and then changed his mind and fired Stanton four months later. His replacement was Lorenzo Thomas, a drunk desk jockey (Johnson had a type) whose main qualification seemed to be his lack of any. After he accepted the job, as Wineapple tells it, Thomas very meekly approached Stanton to tell him that he was in charge, then attended a masquerade ball, then got hammered, and was found the next morning wandering the streets of Washington telling pedestrians that he intended to raise an army to drive Stanton from his office.

Stanton moved his belongings into the War Department, barricaded the doors, and refused to leave the building. This wasn’t normal. Johnson had already said his critics should be hanged. He had stated he would not sic the Army on Congress—which is the kind of thing you only really say if you’ve thought about it. Now some neighborhood drunk was going to take over the War Department. The House finally had its actionable offense. In 1868, three years after Johnson took office, the chamber voted to impeach.

Stevens, Boutwell, and their allies were up against more than just an unhinged president with a drinking problem. They also had to deal with nervousness and dissent within their own ranks. Although Republicans were mostly united in their antipathy to Johnson, they broke down into disparate factions on impeachment. There were the die-hards, of course, and the outright opponents, but the rest were subject to the whims of the moment—people who believed that, yes, the president was bad, but they should convict him at the ballot box, or who gave lip service to the cause but whose true passion was fiscal responsibility. (This last one was a real concern: Because Johnson had no vice president, his removal would have placed Senate president pro-tem Ben Wade in the Oval Office—a nightmare scenario for hard-money bankers.)

In other words, they had to confront the Washington process scold. Today, the most ardent supporters of impeachment on the left are plenty familiar with the type—these are the people obsessed with the means of governance rather than its ends. In the minds of process scolds, the only thing worse than the problems is the act of doing something about those problems. They are duly concerned about possible threats to pluralism, but tut-tut about the discourse when a Muslim congresswoman says she wants to “impeach the motherfucker” who called for Muslims to be banned from entering the United States. Their response to investigations always involves more investigations. These are the people who invented the subcommittee.

For impeachers of any era, the process scolds represent their the most vexing opponent, because on a fundamental level they disagree about what impeachment should be for. Is this about a specific violation of the law? Does it require a narrow, targeted investigation? Or is it about everything?

These two articles of impeachment were the subtext of everything else. The president was a white nationalist who was nullifying a war.The impulse to make impeachment about something narrow and specific is what led Congress to devote the first eight articles of the Johnson impeachment to the Tenure of Office Act. But there was more to it than that. The ninth article focused on charges that Johnson had circumvented the chain of command to give direct orders to a general. (Not a small deal in 1868.) The next two articles are the ones that no one talks about—in its coverage of the Clinton impeachment, CNN dismissed Article 10 as a “historical curiosity”— but they got to the heart of the matter, because Stevens wrote them himself.

They’re sort of omnibus provisions. Article 10 indicts Johnson for his behavior on the Swing Around the Circle Tour—not just for his death threats against members of Congress and other critics, not just for a long, rambling aside about being Jesus (?), but also for his role in enabling white supremacist violence. It quotes extensively from his speeches. In St. Louis, for instance, he’d said that the people massacred in New Orleans were the real traitors, that the white people who did it were merely protecting themselves from the coming race war, and that the “Radical Congress” would “disenfranchise white men.” Article 11 focused on his denigration of Congress, and his overall pattern of obstruction. This was included not because it was merely rude. These articles were the subtext of everything else; Johnson’s antipathy toward Reconstruction was the reason there was a Tenure of Office Act. The president was a white nationalist who was nullifying a war.

You already know how it ends, of course. The trial lasted more than two months. There were tactical errors by the impeachment managers, and a whole lot of what people these days would call “gaslighting.” At one point, one of Johnson’s personal attorneys poo-poohed the notion that a new masked group was terrorizing the South; within three years, Johnson’s attorney general would be working for the Klan as a lawyer. Opponents of Reconstruction had to lie about what was happening because they, too, knew that this wasn’t just about cabinet appointments. After a characteristically strange trial presided over by a chief justice with presidential ambitions of his own, Johnson was acquitted by one vote—our friend Edmund Ross, of Kansas.

Decades after Profiles was published, Ross continues to haunt Washington as a sort of patron saint of forbearance whose name is invoked whenever a constitutional crisis is in the offing. As the Watergate scandal accelerated in 1973, Kansas Sen. Bob Dole told reporters he had started reading up on Ross. “I wouldn’t mind losing my seat if the man is innocent and I voted to clear him,” he said of Nixon.

In 1999, in the midst of the Clinton impeachment, the New York Times heralded Ross as the name that comes up “whenever people talk about courage, honor and duty.” Ross was “a man who lived to see himself vindicated by history,” and “chose personal ruin rather than betray his principles,” the author wrote, while casting Johnson as a victim of partisan overreach. The impeachers “wanted to punish the defeated Confederate states rather than continue Abraham Lincoln’s policy of reconciliation, as Johnson did.”

Johnson—and Ross—benefited from a myth that took hold over the century that followed their impeachment drama. Successive generations of historians flipped the script on Reconstruction, framing white Southerners as victims of a tyrannical Northern regime. Reconstruction governments were painted as hopelessly corrupt, and Radical Republicans—such as Stevens—were on a power trip. The Lost Causers had joined up with the process scolds.

By the time Clinton went on trial in the Senate, a more reasoned consensus had emerged among historians, but the political press continued to portray Johnson as a victim. It got to be too much for Columbia University professor Eric Foner, the nation’s foremost Reconstruction scholar, who lashed out at the coverage at a 1999 panel.

“It’s unbelievable how ignorant of American history they are,” he said.

“They got in their mind the idea that well, Clinton’s a good guy who a bunch of fanatics in Congress were trying to get rid of, so that’s what happened to Andrew Johnson, and a good analogy. It was appalling.”

At least a part of the JFK myth is true: After casting his vote against conviction, Ross was vilified by members of his party, and he did lose his seat in the Senate. But it wasn’t a terribly long exodus—he was later appointed governor of New Mexico, and eventually many of his one-time critics were ready to move on. James G. Blaine, a Maine Republican who voted to impeach, later argued that conviction “would have resulted in greater injury to free institutions than Andrew Johnson in his utmost endeavor was able to inflict.” Ross’ rehabilitation coincided with a shift in his own party. White Republicans steadily lost enthusiasm for Reconstruction in the decade after the impeachment, and Jim Crow took hold across the South.

But JFK—or Ted Sorensen—left out some important details about the courageous Ross. For one thing, his vote wasn’t as critical as it’s been portrayed; Johnson’s defenders had more potential no votes in their pocket that they didn’t end up using. More importantly: He was probably bribed to vote that way! Or at least, the people doing the bribing seemed to think as much. There was a lot of shadowy stuff going on in the run-up to the vote, and Ross himself owed his job to some fairly brazen horse-trading back in Kansas. When the president’s acquittal was complete, Ross quickly returned to Johnson with a laundry list of favors, including patronage jobs for his personal associates as Indian agents, and ratification of a treaty giving away Osage lands to a railroad company. That’s a far different story about institutions and ideals. Sabotaging efforts at protecting the civil rights of Black Americans in order to profit off American Indians really does take some of the shine off the halo.

It is all the more striking because the people Kennedy takes to task in these chapters are, in many cases, his most distinguished Massachusetts predecessors. Butler is referred to, on multiple occasions, as “the butcher of New Orleans,” because a resident of the city was executed for treason on his watch in 1862; the actual massacre of Black residents of New Orleans that precipitated the impeachment is never mentioned. Kennedy takes aim at Sen. Charles Sumner (who at the time of the Johnson impeachment still bore the scars of a savage beating at the hands of a South Carolinian); and Wendell Phillips, of the National Antislavery Society; and George Boutwell, an abolitionist who served as impeachment manager and whose seat in Congress Kennedy would one day hold.

Kennedy and Sorensen show their hand later in the book when they savage Adelbert Ames, another Massachusetts Republican, who moved to Mississippi in the 1870s to serve as governor during Reconstruction.

No state suffered more from carpetbag rule than Mississippi. He was chosen Governor by a majority composed of freed slaves and Radical Republicans, sustained and nourished by Federal bayonets. One Cardoza, under indictment for larceny in New York, was placed at the head of public schools and two former slaves held the offices of Lieutenant Governor and Secretary of State. Vast areas of northern Mississippi lay in ruins. Taxes increased to a level fourteen times as high as normal in order to support the extravagances of the reconstruction government and heavy state and national war debts.

Reconstruction, in their words, was “a black nightmare the South could never forget.”

You can tell a lot about people by the lines they choose to draw. The implicit argument for Ross was that the creation of a white supremacist state through terrorism was not such a line, but that using a constitutional mechanism to remove the president who was creating such a state was. Blaine said it pretty much directly. This is the eternal lie of comity and decorum, the cowardice of compromise, though the stakes have almost never been as high as they were then, not even now.

The Johnson impeachment got bogged down in a morass of legal procedure and political calculations. It was suffused with paranoia and sometimes slapstick, but it was fundamentally about values and power, and about what kind of country would emerge out of its greatest conflict. Plenty of people—“people of their time,” as the apologia goes—understood that bloodshed was the price of inaction, that there was nothing courageous about meek deference to power.

The real tragedy of the trial wasn’t poor, pathetic Edmund Ross losing his seat. When the vote fails, Wineapple takes us to places that Kennedy never ventured in his book—churches in Charleston and Memphis where African Americans mourned what they knew they’d lost, steeling themselves for the fight to come. They knew what the impeachment was really about, and they knew who had won. As Foner put it at that panel, “Andrew Johnson was impeached over violating a fairly minor act of Congress, whereas his real crime was trying to deprive 4 million American citizens of all their rights.”

Wineapple is too serious and disciplined a historian to say exactly what we should think about all this. The pieces are there, though, and it’s not my book, so here goes: At least they impeached the motherfucker.