The Democratic Primary Is Over. The Battle for the Party’s Future Is Just Getting Started.

Damian Dovarganes/AP

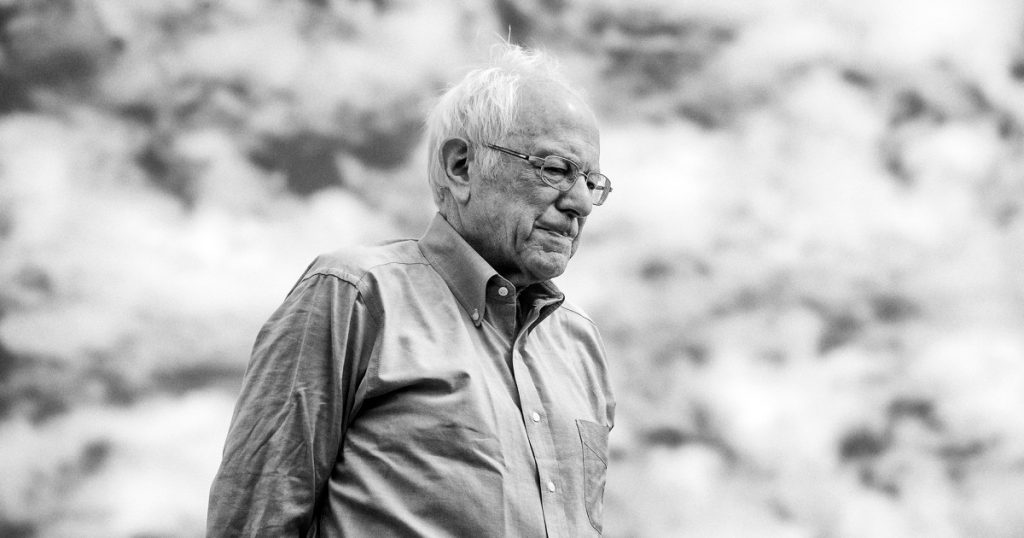

For indispensable reporting on the coronavirus crisis and more, subscribe to Mother Jones’ newsletters.When Hillary Clinton dropped out of the presidential race in 2008, she did so in an immaculately choreographed speech before of a mass of supporters at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC, where she boasted of putting “18 million cracks” in the political glass ceiling. When Bernie Sanders dropped out in 2016, he did so on the biggest of stages—at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. But on Wednesday, the democratic socialist senator from Vermont ended his second and likely final campaign for president under far more demure circumstances: a 14-minute address to the nation via livestream, from an office in his hometown of Burlington, Vermont.

The announcement—the day after a primary in Wisconsin that his campaign not only didn’t contest, but actively discouraged voters from participating in in-person due to the coronavirus pandemic—came weeks after the race was effectively decided and long past the point when Sanders himself had begun to shift his focus from winning votes to making a point. The pandemic crystallized “what this campaign is about,” to use his favored turn of phrase, even as it made the campaign itself unfeasible. Joe Biden, who is now the de facto Democratic nominee, had already announced his intention to skip the next debate and had begun discussing his vice presidential picks. Officially, the Democratic primary ended today. But it felt like it ended a long time ago.

Since 2016, much ink has been spilled—a lot of it unfairly—about whether Sanders had poisoned the well for Clinton by keeping his campaign going until the convention and whether he had worked hard enough to bring his supporters on board for the nominee in November. (Clinton voters were more likely to support John McCain in 2008 than Sanders voters were to support Trump.) There will be holdouts of course, as there always are, but the message from the top couldn’t be clearer. Sanders, as he often has over the last month, struck a conciliatory tone on Wednesday, promising to work with a rival he considers a friend “to defeat Donald Trump, the most dangerous president in modern history,” and conceding that Biden’s massive delegate lead left no suspense as to the final outcome even if the remaining primaries were to proceed as scheduled. Still, he insisted, his campaign had prevailed in another sense.

“Our movement has won the ideological struggle in so-called red states and blue states and purple states,” Sanders said. He rattled off a succession of policies his campaign had helped push into the national conversation, such as a $15-an-hour living wage and a single-payer health care system.

“It was not long ago that people considered these ideas radical and fringe,” Sanders said. “Today they are mainstream ideas and many of them are already being implemented in cities and states across the country. That is what we have accomplished together.”

Whether Sanders had truly won the ideological debate is an argument that isn’t likely to end soon. In no small part because of Sanders, the ground has shifted substantially over the last five years on issues like a living wage, climate action, and, above all else, Medicare for All. Even Biden has embraced more left-leaning proposals on tuition-free college and student-debt forgiveness. He also backed Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s bankruptcy reform plan—effectively conceding the argument on a policy that he spent several decades defending. But ultimately, the nominee will be the one candidate who spoke loudest and most consistently against a single-payer health care system, and whose campaign represented a continuation of Democratic politics as usual.

Sanders on Wednesday, and frequently throughout the campaign, cited polling data showing that voters (even in states he lost) supported his policy ideas. But the ideological debate is about more than just policy. Biden’s ideology is rooted in a belief in bipartisan dealmaking and moderation, a notion that Barack Obama was a very good president, and that what America needs right now is someone who will not “fundamentally change” your life but who will proceed cautiously, without blowing up the system or provoking a backlash. (The last one is easier said than done.) If you want to know which ideology most Democratic voters preferred, don’t look at issue polling; look at how they voted.

But there are green shoots of hope for Sanders’ movement in those vote totals, too. The Vermont senator’s fortunes were done in by his inability to win over older voters in large numbers—in particular, older Black voters in the South, who helped hand Biden a resounding victory in South Carolina and build an insurmountable delegate lead on Super Tuesday. Look at the numbers from the Mississippi primary. Among Black voters over the age of 60, according to one exit poll, Biden beat Sanders 96–3. But even in places where Sanders struggled—and struggled in comparison to his 2016 performance—his numbers spoke to an enduring strength: Young voters trust him far more than they trust anyone else in politics. In Michigan, a state he lost handily, Sanders won voters under the age of 30 by 57 points. It was like that all across the country. And he returned to the theme in his concession speech.

“Not only are we winning the struggle ideologically, we are also winning it generationally,” Sanders said. “The future of our country rests with young people, and in state after state, whether we won or we lost the Democratic primaries or caucuses, we received a significant majority of the vote—sometimes an overwhelming majority—from people not only 30 years or younger, but 50 years or younger. In other words, the future of this country is with our idea.”

And this, as much as the policies he went to bat for, is the enduring legacy of Sanders’ campaigns. He exposed a sharp generational divide in Democratic politics between people over, say, 45, and people under it—a cohort of voters whose political educations were forged by Trump, the Great Recession, and the Forever War, and who can now add to those three horsemen a pandemic and the specter of depression. These voters are massively in debt, can’t afford housing and insurance, and are increasingly cognizant of the precariousness of the planet.

In the immediate term, there’s no compelling evidence that Sanders’ voters won’t, by and large, come around to supporting Biden. Trump’s dual insistence that the Democratic establishment screwed over Sanders, and that Biden is also a socialist who shares most of Sanders’ priorities, is perhaps not the genius stroke Republicans think it is. But the generational tension isn’t going anyway. Not long after Sanders finished speaking, a coalition of millennial and Gen Z–based organizations, such as Justice Democrats and the Sunrise Movement, released a letter urging the Biden campaign to make a series of accommodations—such as hiring new staff and adopting more aggressive positions on climate, immigration, and education—to generate the “energy and enthusiasm” it needs from young voters in November.

Sanders’ support came from a real anger and frustration—and, yes, hope—that isn’t going to be sated by Biden, win or lose. His voters are outnumbered in the present. But the future, they believe, may still be theirs.