ICE Predicted Record-Breaking Arrest Numbers. Instead, They Keep Dropping.

An immigrant is arrested during an Immigration and Customs Enforcement operation in Los Angeles, California in February 2017.Charles Reed/AP

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement may be succeeding in instilling widespread fear among immigrants, but it is arresting far fewer people than it once did. After taking nearly 300,000 people into custody in 2011, ICE is is on track to arrest fewer than 140,000 immigrants this year.

New data released by ICE on Thursday show that ICE officers arrested 34,546 people between October and December 2018—the start of the current fiscal year—a 12 percent drop from the same period in 2017. The data offer a sharp contrast with the record-breaking deportation numbers former ICE director Thomas Homan predicted at the beginning of the Trump administration. “I think we’re going to get there,” Homan said in July 2017, referring to the deportation record set in 2012. “Our interior arrests will go up.” That has ended up being wishful thinking on Homan’s part.

Faced with diminishing cooperation from cities and states as progressive jurisdictions push back against the administration’s harsh immigration agenda, ICE has far less capacity to arrest people than it did at the beginning of the Obama administration. Sanctuary cities and counties are no longer sharing arrest information with ICE, forcing agents to find individual immigrants in their communities instead of picking them up at jails. Those operations are far more resource intensive and reduce ICE’s overall efficiency.

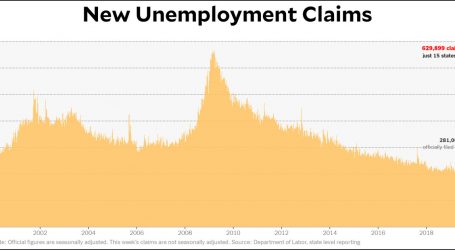

ICE arrests reached a record high at the end of the George W. Bush administration and remained high during Barack Obama’s first term. The increase was driven by the Secure Communities program, which gave ICE officers unprecedented access to information on people local jails were taking into custody—including their immigration status. The spike in arrests led to a backlash, and many jurisdictions took on the “sanctuary cities” mantle and stopped coordinating with ICE, which lost the ability to pick up immigrants and send them to immigration detention when they were released from jail.

In 2014, the Obama administration ended Secure Communities and replaced it with a program that directed ICE officers not to arrest most immigrants without criminal records or with minor convictions. Arrests fell from 288,392 in the 2011 fiscal year to about 110,000 annually during Obama’s final years in office.

President Donald Trump’s first homeland security secretary, John Kelly, quickly reinstated Securities Communities and gave ICE officers broad discretion to arrest immigrants without criminal records. In Trump’s first year in office, ICE arrests jumped by 41 percent—and by 171 percent among people without criminal records. But that has proved to be about ICE’s ceiling under Trump. Total arrests peaked in August 2017 and have been mostly declining since.

The biggest shift under Trump remains the dramatic increase in arrests of people without criminal records. Thirty-six percent of immigrants arrested by ICE in December 2018 were non-criminals, according to the new ICE data, a new high and more than double the rate during the last month of the Obama administration.

Because of the reduced cooperation of local police chiefs and sheriffs, a growing portion of the arrests are taking place “at large”—in immigrant communities rather than at jails. Those arrests, which increased by about a third in Trump’s first year in office, tend to create the most fear since they are far more visible and likely to sweep up undocumented immigrants that ICE is not actively targeting. Still, the at-large arrests, which increased by just 1 percent between 2017 and 2018, may have peaked, too. The time-consuming arrests require multiple officers, and ICE can only conduct so many of them.

Asked about the decline in arrest on a call with reporters on Thursday, Nathalie Asher, the acting head of ICE’s arrest and deportation operations, cited the record number of families crossing the border. As a result of that “explosion,” Asher said, she has had to redirect resources to the border. That, in turn, has led to a decline in interior arrests.

That may explain the relatively small decline in recent months, but it does not explain why ICE has been unable to come anywhere close to the arrest levels reached in previous administrations. The reality is that without the cooperation of local governments, ICE is no longer as powerful as it once was.