How America’s Brutal 15-Year War in Iraq Changed Its Environment Forever

For decades, Iraq has struggled with water reductions as a result of dams in neighboring Turkey. But the Ilisu dam, a controversial new hydropower station set to begin operations in the coming months on the Tigris in southeast Turkey, could reduce the river’s flow into Iraq by 56 percent, according to an Iranian official who warned that Iran may also suffer. The dam is part of the Southeast Anatolia Project, a long-planned infrastructure build up that includes 22 dams.

In Iran, a new dam on the Sirwan river put the flow of water into Kurdistan, the restive northern region of Iraq, in jeopardy. A campaign group called Save the Tigris sprang up in Erbil, the capital of Kurdistan, to advocate against it.

But the government in Kurdistan took its own measures to secure its water. Last March, officials in the region announced a set of roughly 20 small- and medium-sized dam projects aimed at protecting irrigation and drinking water supplies.

“The snowmelt in the mountains of Kurdistan is not how it used to be,” Alwash said. Without that freshwater, the agricultural plains in southern Iraq are becoming saltier and less able to grow crops, raising the risk of food shortages.

“If we are what we eat, then we’re all Kurds in one way or another.”

“If we are what we eat, then we’re all Kurds in one way or another,” he said. “That line gets a lot of applause in Kurdistan but it does not get a good reaction in southern Iraq. They don’t like the idea of being related in nature.”

More than half of Iraq’s population is already at risk of food shortages as a result of ongoing conflicts with militants, according to a U.N. World Food Program report last April. In 2015, at the peak of the so-called Islamic State’s control over huge swaths of the country, the militant group cut off the flow of water through a dam in Ramadi, in central Iraq. Food prices soared by up to 58 percent in some regions.

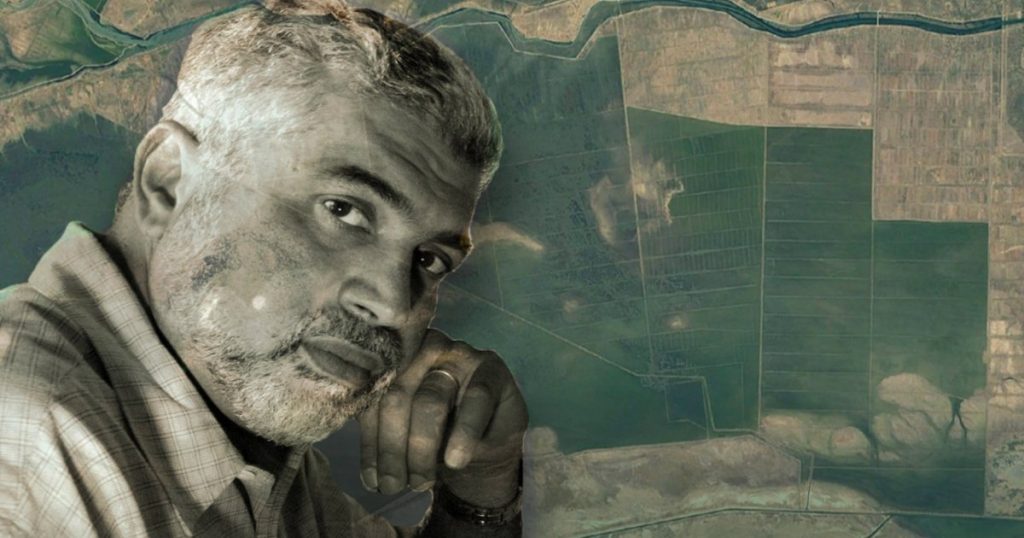

Alwash worries an arms race over water will make the region even more of a tinderbox. With his marsh projects well established, he now finds himself jet-setting around the world on a quixotic mission to convince policymakers to avert their attention from ongoing conflicts to consider the much bigger and, he believes, much more deadly, conflicts of the near future over water. He returned to Amman from Vienna just days before a recent interview, and planned to leave for Kuwait soon after.

The war to rout Islamic State from northern Iraq has brought other environmental crises. The militants routinely torch oil fields before retreating from an area, leaving thick clouds of smoke that blacken white sheep and burn for months. Worse yet, there is virtually no international funding set aside to clean up the pollution, according to a report published in November 2017 by the Dutch nonprofit PAX.

March marks the seventh year of civil war in Syria, a conflict that some call a “climate war” because it began with unrest sewn by the country’s worst drought in roughly 900 years. It also marks the third year of Saudi Arabia’s bombing campaign in Yemen. President Donald Trump’s decision to open a US embassy in Jerusalem has escalated tensions between Israel and Palestine. Turkey is increasing its military intervention into Kurdish-controlled parts of Syria.

Yet Alwash is hoping he can broker talks to begin cooperative water projects between Iraq, Turkey, Iran and other neighboring countries.

He said he’s ready to say something else controversial: militants like ISIS are actually right about one thing: The region needs to unite itself. Alwash said he envisions “a Middle East without borders, built on the idea of creating cooperation on water instead of tension.”

“The Islamists are looking for a borderless Middle East, they want to do it with Syria and political Islam,” he said. “I have the same goal. I want a Middle East without borders. But I want it with democracy and plurality of a political system.”

“The environmentalists of Iraq and the Islamists of Iraq have the same goal,” he added with a facetious laugh, “just a different roadmap.”