Hoods, Hazing, and Heavy Drinking: A Look Inside an Elite University’s Fraternity Culture

Looking for news you can trust?Subscribe to our free newsletters.

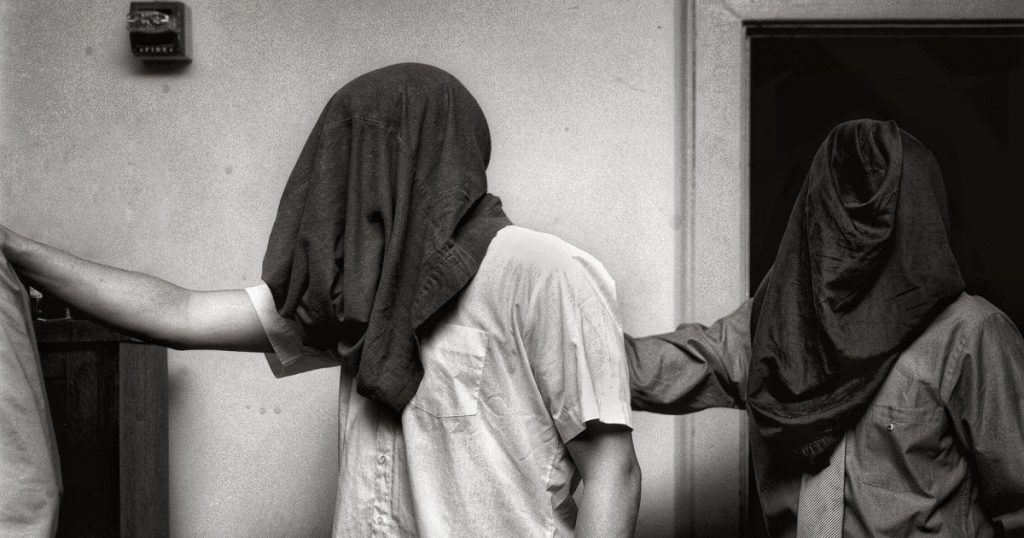

When photographer Andrew Moisey entered his brother’s fraternity house in 2000, Greek culture—and the toxic male culture often associated with it—had yet to encounter the kind of scrutiny it is experiencing today, and the United States was about to elect George W. Bush, a leader Moisey refers to as the “Frat Guy in Chief.” With a small camera in tow and the bravado of a new photographer, Moisey began taking pictures of life inside the still-unnamed house at the University of California-Berkeley. “I didn’t have an agenda,” he says, and perhaps that was why the fraternity brothers let him stay. But in the back of his mind, Moisey knew he was witnessing something important: the private playground of the country’s future leaders. Eighteen years later, his pictures are being published in a new book, and amid the #MeToo movement, his work has assumed a heavier tone. “This is not just a secret society,” Moisey says. “It’s our society.”

The American Fraternity (published October 15 by Daylight), Moisey’s first photo book, collects his images of men undergoing initiation rituals, hanging out behind the closed doors of their fraternity house, and enjoying the kind of drunken debauchery recently spotlighted in the hearings for Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. Among the photographs, Moisey includes pages from the fraternity’s 60-year-old “ritual manual,” which he found abandoned on the floor in the house. The scans help contextualize the brothers’ place in a centuries-old system of privilege and precedence, and contrast the high-minded ideals of fraternity with the organization’s often violent, misogynistic reality.

While he says he didn’t witness assaults of the kind Kavanaugh is accused, Moisey admits, “It would not surprise me if I missed something that was exactly the same.” He stresses that a majority of the brothers he knew were good people who grew into men he looked up to. “I feel for them now that this book is being released at a time that is going to make all of them look like Brett Kavanaugh. And they’re not,” he says. But, by belonging to a fraternity, “they were part of a culture that protects the worst impulses men have.”

Witnessing the brothers’ behavior sometimes gave Moisey pause. “Every once in a while I was like, ‘Woah—I would not be like this,’” he remembers. An emphasis on what Moisey carefully describes as “conquests of women” was, he says, protected and cultivated within the house. That phenomenon would go on to have a direct effect on American culture at large, as fraternity brothers across the nation became powerful figures.

In all, Moisey photographed life in the house over seven years. By the end of the project, he says, “I knew more about the house than some of the guys that were in it.”

Viewed from a distance, Moisey says his photographs are not about the acts of one fraternity at an elite university. Instead, his project “is about the source of a problem in our leadership. If people want to know where men get the idea that they can behave like this, my book provides them with one source.”

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey, from The American Fraternity

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey, from The American Fraternity

Andrew Moisey, from The American Fraternity

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey, from The American Fraternity

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey, from The American Fraternity

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey

Andrew Moisey