Geoengineering and Ocean Acidification Off the Coast of California

One of the possible solutions to climate change is geoengineering. Various types of geoengineering have been proposed over the years, but the best studied of them is to simply release vast amounts of aerosols into the atmosphere. The aerosols reflect light and thereby reduce the amount of solar heat that reaches the surface of the earth, much the same as a large volcanic eruption does. Even in massive quantities, an aerosol spraying program turns out to be surprisingly cheap and practical.

So why not do it? The biggest reason is that we don’t know what kinds of unexpected effects an aerosol spraying program might have. The second biggest reason is that we do know what some of the expected effects of aerosol spraying are. In particular, it does nothing about the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, and CO2 does more than just produce warmer temperatures. It also gets absorbed into the oceans, where it increases ocean acidification.

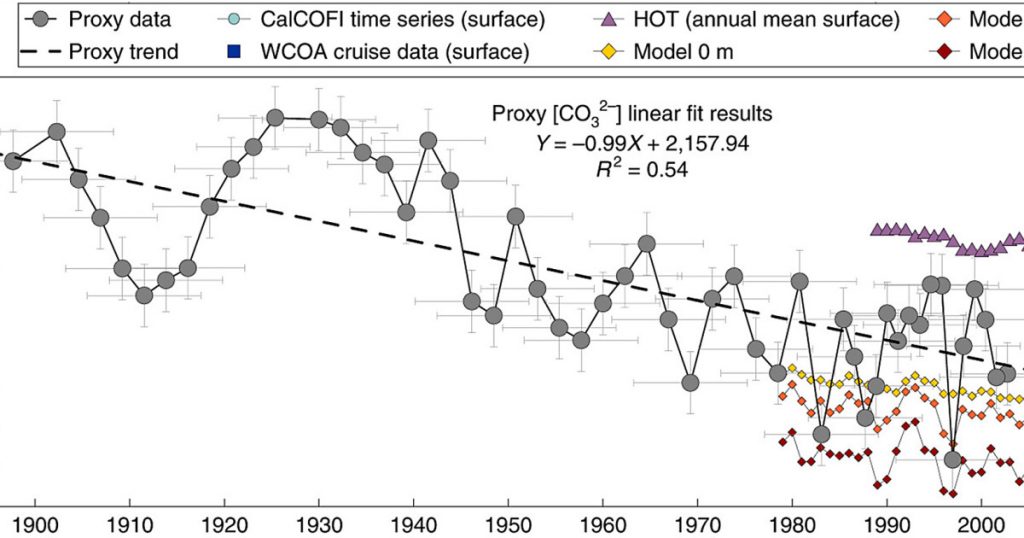

This problem is worse in some places than in others. A new study, for example, shows that ocean acidification off the coast of California is twice as bad as the global average. Researchers measured shell thickness in tiny planktons, which produces an estimate of the concentration of calcium carbonate suspended in ocean water. Here it is:

What we see is a long-term downward trend modified by El Niño oscillations. Calcium carbonate is a base, so a decline in its concentration means that ocean water is becoming more acidic—that is, it has a lower pH. Specifically, the authors estimate that this data represents a 0.21 reduction in pH. Keeping in mind that pH is an exponential scale, like the Richter scale for earthquakes, this means that over the course of a single century the concentration of acid in California’s coastal waters has increased by more than 50 percent, compared to about 25 percent for the rest of the world.

So what does this mean? This is the problem: nobody really knows. It has obvious effects on coral reefs, and it also makes the shells around microscopic sea creatures thinner and more fragile. If acidification increased by another 50 percent over the next few decades, it would . . . probably have a very bad effect. But we don’t know for sure.

This is one of the reasons why geoengineering is a bad solution to climate change. Not only do we know that aerosols would have no effect on ocean acidification, but we’re in the dark about what else they might do. Aerosols in the air for a year or two from volcanic eruptions don’t seem to cause serious problems. But what about aerosols in the air for decades at a time?

It’s possible that eventually we’ll decide to risk it. But we’d sure be a lot better off attacking the disease—too much carbon—instead of the symptom—too much heat. We know exactly what the former would do. The latter is a roll of the dice.